As extremists and fearmongers try to create division, organisers of an exhibition in England fight back with inspirational tales of unity to remind us of how natural it is for Muslims and non-Muslims to stand side by side.

The brief official citation for awarding the Victoria Cross, issued by the war office and reported in The London Gazette in December 1914, gives only the barest hint of the horror that Khudadad Khan must have endured on October 31 that year.

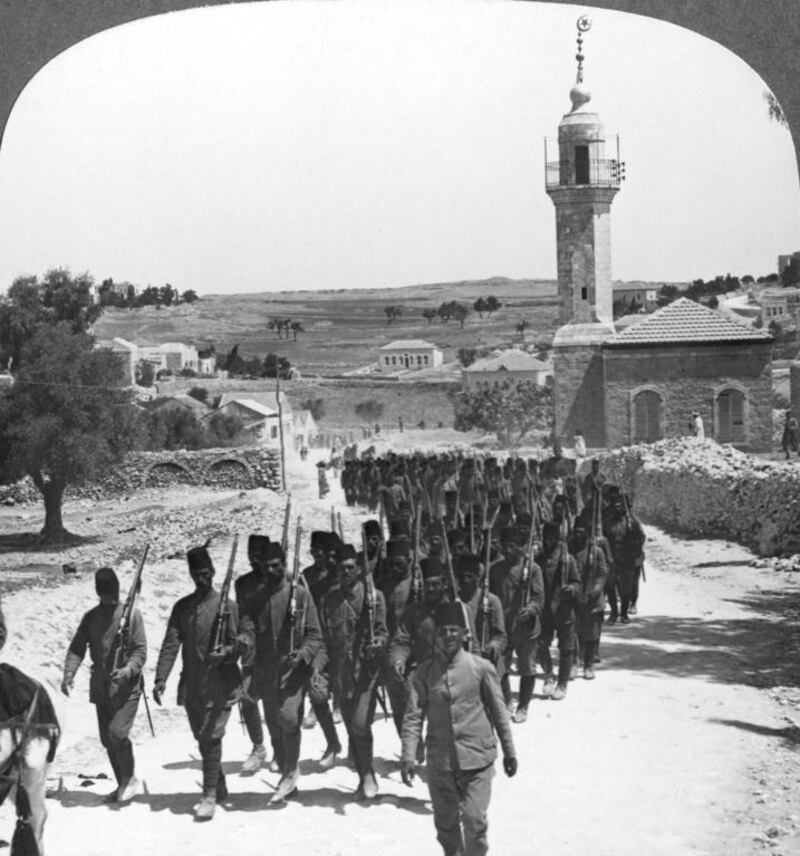

As a sepoy (soldier of the Indian army serving under British orders) with the 129th Duke of Connaught’s Own Baluchis in the First World War, Khan was sent to the front lines to relieve the exhausted British Expeditionary Forces fighting a desperate battle to prevent the rapidly advancing Germans reaching the crucial English Channel supply ports.

Outnumbered five to one and pounded by artillery, the Baluchis made their stand at a Belgian village called Hollebeke, delaying the Germans long enough for Allied reinforcements to arrive.

“The British officer in charge of the detachment having been wounded, and the other gun put out of action by a shell, Sepoy Khudadad, though himself wounded, remained working his gun until all the other five men of the gun detachment had been killed,” The Gazette reported.

In fact, as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission later recorded, Sepoy Khudadad’s machine-gun position was finally “overrun by Germans and everyone was bayoneted or shot, Khudadad Khan among them”.

Badly wounded, “when night came he crawled away and rejoined what was left of his regiment. The actions of the Baluchis had held up the Germans long enough for other Indian and British troops to get to the area and halt the attack. The ports remained in Allied hands”.

In January 1915, while recovering in hospital at Brighton on England’s south coast, Khan, 26, became the first Muslim to receive Britain’s highest military honour, the Victoria Cross, awarded only for the “most conspicuous bravery in the presence of the enemy”.

Born in Chackwal, Punjab, in present-day Pakistan, he received his medal from Britain’s King George V in person. He survived the Great War and died in Punjab, aged 83, in 1971.

Khan’s heroism on behalf of India’s distant emperor and a country he had never visited, is just one of the tales that make up the Stories of Sacrifice exhibition developed by the British Muslim Heritage Centre in Manchester, England.

The purpose of the exhibition is to serve as a reminder of a largely forgotten shared heritage that bonded Muslims and non-Muslims long before modern security fears made diversity such a sensitive issue for British communities.

The exhibition’s curator is Dr Islam Issa, lecturer in English literature at Birmingham City University, and during his research he unearthed a telling new statistic.

Until now, it has generally been accepted that about 400,000 Muslims served with the Allies during the Great War. But an exhaustive trawl by Dr Issa through thousands of personal letters, archives, regimental diaries and census reports revealed that more than 885,000 Muslims, including Indians and Arabs, had responded to the Allies’ call to arms.

About half were from what was then known as British India, with a similar proportion Arabs, including at least at least 280,000 North Africans and 170,000 Egyptians. Still unverified are Africans from Senegal and Mali.

Sadly, even as centenary commemorations placed the war at the forefront of Britain’s national consciousness, research last year by the British Future think tank found that only one in five British people were aware of the Muslim contribution to the war, and that almost no one had any idea of its scale.

“Our sense of national identity is shaped by our history,” said Sunder Katwala, director of British Future. “Yet few people are aware that the multi-ethnic army of 1914 looked much more like the Britain of 2014 than that of 1914, nor that Muslims fought alongside Christians, Sikhs and Hindus on the battlefield.”

The sacrifices they made, said Dr Issa, “have left behind a positive legacy, but even Muslims don’t realise the extent of the contribution.

“It can only be positive, I think, for the British public – and for Muslims and non-Muslims everywhere, to learn that they contributed in this way, well before we had any ideas about integration and so on.”

Many of the stories in the exhibition “show that diversity and integration were a sort of natural given state that people didn’t have to aspire to – it just happened, whether it was fighting together or playing football together, or whether it was the kinds of provisions that were made by the British officers for their Muslim soldiers”.

Regimental diaries held at the National Army Museum and the National Archive reveal the lengths to which British officers went for their Muslim troops, arranging special areas for prayer on board troop ships, making provisions for Muslims in hospital to fast, and organising separate butchers and kitchens to prepare food.

All of this – to say nothing of the valiant acts of self-sacrifice by Muslim troops, about 89,000 of whom were killed fighting for Allied forces under French or British command – “shows toleration from the non-Muslim side and certainly integration and diversity as well from the Muslim side”, said Dr Issa.

“It wasn’t seen as something special, it was a norm, and I think that’s maybe where we’ve gone wrong today.

“Having done this research I realised we shouldn’t have to say ‘Look at this contribution’. We should already know about it and be appreciative of it.”

The Manchester exhibition does not pretend there were not problems.

Amid false rumours that the Kaiser had converted to Islam, some Muslims deserted to the Germans, and one section tells the story of the 15th Lancers, a British Indian cavalry unit that served with distinction in France in 1914 but drew the line at fighting fellow Muslims when they shipped to Basra.

Another tells of the infamous revolt of 800 Indian troops in Singapore in February 1915 in which 39 European soldiers and civilians were massacred. British and French soldiers put down the revolt and executed 37.

But such events were few and far between.

Many of the Muslims killed in the war died in Mesopotamia, where the British suffered terrible defeats before finally pushing the Ottoman forces out of what is now Iraq.

More than 4,000 Indians are buried in Baghdad’s North Gate War Cemetery, where they lie alongside Lt Gen Sir Stanley Maude, their British commander-in-chief, who died at Baghdad in November 1917, shortly after the city fell to the Allies.

It is little appreciated that thousands of Muslims also paid the ultimate price on the Western Front.

The Menin Gate, the imposing memorial to the Allied dead at the entrance to the bitterly contested Belgian city of Ypres, bears the names of 400 Indian soldiers, many of them Muslims, with no known grave.

In France, the Indian Memorial at Neuve Chapelle, where the Indian Corps fought its first major action of the war in March 1915, commemorates 4,742 Indians who were also lost without trace.

The column at the centre of the memorial is guarded by two stone tigers and bears the legend “God is one. His is the victory”, in English, Arabic, Hindi and Gurmukhi.

In October 2014, on the eve of the war’s centenary commemorations, two former heads of the British army wrote to the Daily Telegraph “to highlight one man whose service exemplified the courage of many who served in the First World War”.

“The gallant Sepoy Khan embodies that history.”

The war had “brought together soldiers from across the Empire to fight for Britain”, they wrote in a letter also signed by Sughra Ahmed, president of the British Islamic Society, among others.

It was “important today that all of our children know this shared history of contribution and sacrifice if we are to understand fully the multi-ethnic Britain that we are today”.

The exhibition at the British Muslim Heritage Centre has been funded by the Covenant Fund, set up by the UK ministry of defence partly to support “community integration projects”.

In the face of what has been regarded as divisive government policies aimed at preventing the radicalisation of young Muslims, it is a perhaps more enlightened attempt to reach out to Islamic communities and emphasise the common ground they share with all British citizens.

Within the British army today there are 650 serving Muslims, supported by the Armed Forces Muslim Association, “helping support these dedicated men and women perform their military duties in full without compromising their faith”.

On its website, the association makes no bones about Sepoy Khan and the other two Muslim soldiers who were awarded the Victoria Cross in the First World War. They are simply “our heroes”.

There will, Dr Issa acknowledged, be those who say the war was just another example of the British Empire’s exploitation. But for him, highlighting the negative “is beside the point really”.

“These are individual stories, these are huge numbers, and at the end of the day it is important to realise that there was a common experience shared by Muslims and non-Muslims in this country 100 years ago.”

He does not, he said, “want people to think of this as some sort of apologetic show or something that is trying to prove a point about integration”.

“On the contrary, I think this research says, look: so many Muslims have always contributed and they already share so much with non-Muslims.

“We’ve long neglected that and, by documenting it, we’re saying that Muslims in the West don’t have ‘something to prove’ and don’t need to get swept into calls for apologetic rhetoric.

“What we really need is to know the facts of history more closely.”