The number of workers in the UK in precarious positions where they could lose their jobs at short or no notice has grown by almost 2 million in the past decade, as businesses insist on using more self-employed workers and increasingly recruit staff on temporary and zero-hours contracts, analysis for the Guardian has revealed.

More than one in five workers, some 7.1 million people, now face precarious employment conditions that mean they could lose their work suddenly – up from 5.3 million in 2006, according to analysis of official figures conducted by John Philpott, a leading labour market economist. Half of the biggest group – the self-employed – are in low pay and take home less than two-thirds of the median earnings, according to the Resolution Foundation thinktank. Two million self-employed people now earn below £8 per hour.

The extent of the precarious work phenomenon emerges as a Downing Street-commissioned inquiry into modern employment practices gears up. Amid growing concern about the social impact of a workforce increasingly divided between low-paid, low-skilled and insecure work and higher-paid, higher-skilled employment, the Guardian is publishing a series of articles on the consequences of the change for the kind of workers described by Theresa May as “just managing”.

The government is concerned that the lack of training offered in precarious work, particularly in self-employment, is “completely backward”, according to a No 10 source. The fear is that it entrenches low pay and hinders career progression to higher earnings.

Meanwhile, 750,000 more people are on zero-hours contracts than in 2006, and 207,000 more people are working as temps, according to Philpott’s analysis of the government’s labour force survey. Some of the zero hours workers may also be included in the temp count – 32% in the most recent set of figures.

“There is something profound going on and all of this poses a potential risk to social cohesion and a risk to the potential for social mobility,” Alan Milburn, the chairman of the government’s commission into social mobility, told a recent event on precarious working.

The issue has also been prioritised at the Trades Union Congress, which has launched a review of the scale and nature of vulnerable work in Britain.

Companies such as Argos and Tesco use thousands of agency temps. Sainsbury is now using 54 different employment agencies for its temporary warehouse workers. The taxi company Uber and courier firms Hermes and Yodel are among firms relying on 4.7 million “self-employed” workers, although Uber recently lost a landmark employment tribunal case when judges ruled that its self-employed drivers should be treated as workers and paid the “national minimum wage”, enjoy paid holidays and get sick pay.

Anxiety about low pay is running so high that more than 10,000 people called the Acas minimum wage helpline in the five months to September concerned they were not receiving the statutory minimum – a 73% increase on the same period last year, according to figures released to the Guardian. The UK currently has a greater proportion of full-time employees in low pay than all but seven of the 22 developed nations in the OECD.

“The rise in self-employment has been hailed as part of the economy’s success story in the recovery, but for thousands of people it can mask some worrying trends – namely being forced into precarious, low-paid work,” said Ashwin Kumar, chief economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. He pointed out that self-employed families were more likely to live in poverty, with a median income of £209 a week against £384 for employees.

Vulnerable work does not always mean poor pay and conditions, but while many workers choose self-employment or temporary contracts, earnings on average are much lower. Self-employed workers typically earn about half the wage of permanent employees, zero-hours contractors about 40% and temp workers around two-thirds, Philpott said in his analysis for the Guardian, although this is complicated by the variability of hours worked.

The impact of the changes to pay is not spread evenly across the UK. An estimated one in four of all workers in the Greater Lincolnshire area, for example, is forecast to be earning near or below the national living wage or the national minimum wage by 2020 – an increase from one in 10 in 2015, according to analysis by the Resolution Foundation. Other areas badly affected include London, Nottingham, Liverpool and the Tees valley.

The human impact of the phenomenon is also becoming clear. Last year, a review of studies around the world published in the BMC Public Health journal concluded that job insecurity posed a comparable threat to health as unemployment – and that anticipating a job loss could actually have a more significant effect than experiencing it.

Young adults have been hit hardest by the long-term trend. The proportion of working 16- to 20-year-olds in low pay rose from 58% in 1990 to 77% in 2015, while the proportion aged 21 to 25 rose from 22% to 40%, according to Resolution Foundation analysis. Older workers have become less likely to endure low pay.

The attractions of flexible or insecure contracts are considerable to employers and they dispute many of the downsides that unions, workers and analysts have highlighted.

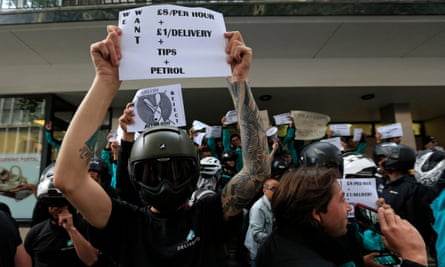

Deliveroo is a multinational company that relies on 8,000 self-employed workers in the UK to deliver takeaway meals by bicycle. By contrast, in the Netherlands and Germany it directly employs 1,500 couriers, which might suggest that its business model, in those countries at least, is not reliant on self-employment. Lawyers for several Deliveroo riders in the UK are at the early stages of considering making a claim against the company for false self-employment, something Deliveroo denies.

But Deliveroo describes its riders as “independent suppliers” and in a statement a spokesman said this status was because “the flexibility this offers is important to them”.

It is not just insurgent tech companies that use large numbers of non-staff workers to deliver their core services. Tesco, Britain’s biggest supermarket chain, said between 35% and 40% of its warehouse workers – some 6,000 – are provided by agencies.

For many of our biggest brands, employment arrangements resemble a Russian doll. Amazon relies on thousands of self-employed workers to deliver its parcels and subcontracts to companies such as Hermes and Yodel, which subcontract to thousands more couriers themselves.

For warehouse workers who are not directly employed, Sainsbury uses a similar multilayered arrangement. It has a contract with De Poel, an agency services provider, which in turn manages contracts with employment agencies, which then hire staff. Sainsbury says the vast majority of these workers have full-time contracts but some drivers are on limited-hours contracts, something the retailer says it is monitoring with the agencies.

“Like all large retailers, working with agencies allows our distribution network to accommodate business needs – Christmas being the obvious example,” a spokesperson said.

That argument about fluctuating demand is a powerful one for many companies. “One of the attractions of flexible contract options for businesses is being able to meet more volatile demand patterns in increasingly 24/7 markets,” said Neil Carberry, director for people and skills at the Confederation of British Industry. Nonetheless, he insists that the trend is not significant. “There have been claims that the mass casualisation of the British labour market is around the corner for 30 years. But the need to retain talent and build productivity in companies mean that directly employed staff will always be the majority of our labour market.”

“No form of contract is inherently problematic,” he added. “It is about how companies deal with their staff … The key thing is good management, and businesses are committed to doing that well.”

Some of the 7.2 million workers now in precarious employment might disagree that is always the case.

‘If it was a slow month I would be worried’

Norma, a mother of three from Rotherham, has been juggling three self-employed jobs to try to make ends meet. She worked six days a week delivering parcels for Yodel, which earned her between £400 and £800 a month before paying her car expenses; she delivered 500 newspapers a week for Whistl, earning about £25 a week; and she ran her own small online business selling cross-stitch craft kits she assembled in her conservatory.

“It was a fine balancing act for the family,” she said. “I never knew how much money was going to be in the bank. If it was a slow month I would be worried about finding extra work from somewhere. I couldn’t make the money I needed in the time I’d got.”

Yaseen Aslam, a former Uber driver, is also self-employed – but succeeded along with another driver in challenging that status at a recent employment tribunal. .

“When I first started minicab driving eight years ago, I used to do 30 hours a week and took home £500 after expenses,” said Aslam, a 35-year-old married father of three from High Wycombe.

“I was self-employed and I felt self-employed. Over time we have lost control of what we were making. There were lots of advance bookings but with technology things changed. We have no sense of what we were going to be making, the prices fell and more drivers came on to the streets. I was getting between £50 and £100 per day before expenses, which was much less. I didn’t have any quality family time and I was busy working all the time just to pay my bills.”

He has found another form of self-employment, again enabled by the internet: trading merchandise on eBay from his home.