It’s a point in 2022’s favour that, rather than violent insurrection or the misery of lockdown, most English-speaking people on the internet are currently preoccupied with a harmless word game. Harmless at the time of writing, I should say – it’s popular enough that some kind of backlash is inevitable. I’m sure any day now Wordle will be revealed as a Bad Thing and I don’t want to speculate how; I am merely here to observe that it is a) a lot of fun b) linguistically interesting, and I’d like to explain why. I may even be able to make you a bit better at it.

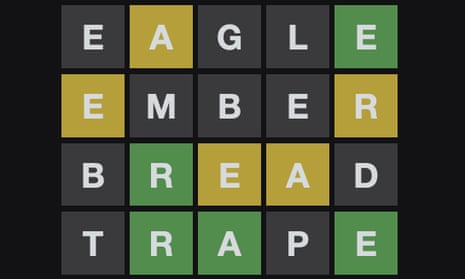

If you don’t already know, Wordle is a browser-based puzzle that gives you six goes at guessing a five-letter word. If your guess includes a letter that’s correct but in the wrong place, it turns yellow (more like ochre – now there’s a good starting word for you). If it includes a letter that’s correct and in the right place, it turns green, allowing you to build on your guesses until you hit the jackpot. The solution to the Wordle in the screenshot above is “craze”.

It’s helpful to understand what Wordle is mainly testing, and I think there are a couple of things: first, your knowledge of the frequency of individual letters in the English language – that is, how common they are (think of the value of letters in scrabble – “q” is 10 because it’s harder to find words that use it, whereas “e” is 1). So it would be unwise, for example, to use “hyrax” as your first guess.

More interestingly, though, it probes your instinct for how letters can be combined. Very often you find yourself thinking: I’ve got an “o” an “r” and a “t”. Do many English words end in “o”? Is “t” a good bet to start the word with? Should it be followed by “r”, or should there be a vowel in between them?

OK, so most of us will have a sense of how to answer these questions already, because we use words every day and have a gut feeling for which sequences are possible where, and which aren’t allowed at all (“ng”, for example, is pretty common in English, but never at the beginning of a word, and “lng” never appears anywhere).

But linguistics can help a bit. There is actually a whole branch of it that looks at the way sounds enter into sequences, and it’s called phonotactics. Each language has its own phonotactic constraints – such as the rule that says “ng” can’t start a word in English (it can, and does, in Māori and Swahili). Then there are rules that determine the possible order of consonants in a syllable: “tr” is fine at the beginning of a syllable but not the end, and the reverse is true for “rt”. “Bl” and “lb” follow the same pattern.

That’s not actually a coincidence. There’s a mechanism behind it called the “sonority sequencing principle” or SSP. Certain sounds, often “hard” ones like “t”, “b” or “g”, are not very sonorous, or resonant. Softer sounds like “r”, “l” and “w” are a bit more sonorous, and vowels are very sonorous. In a syllable that contains consonant clusters, the less sonorous sounds will tend to appear at the beginning, there will be a sonority peak in the form of a vowel, and then a gradual downward slope back to something less sonorous. “Blurb” is a lovely example of this, as is “twerk” or “plump”. “Rbubl”, an impossible word, violates SSP because “r” is more sonorous than “b”, and “b” is less sonorous than “l”. Within this framework, some combinations of sounds are seen way more often than others: “tr” and “pr” are everywhere, but “dw” is pretty unusual, appearing in “dwell” and “dweeb”, with “dz” rarer still – “adzes” may be the only Wordle-able example.

Why do we see this rise and fall pattern with sonority? Basically, it makes things easier for both the speaker (the transition between sounds requires less effort if there’s a gradient rather than a sudden leap) and the hearer (syllables are more distinct when there are less sonorous, more abrupt sounds at the edges). As a bizarre aside, some researchers believe that climate has an effect on the ratio of sonorous to not-so-sonorous sounds in a language. In places with higher temperatures, which can distort high frequency sounds, languages may have fewer consonants and simpler syllables as a result.

Anyway, the reason it’s useful to think about SSP when you’re Wordle-ing is because it can guide you towards more likely sequences and away from unlikely or impossible ones. There is something to beware of here, however, and it’s the fact that in English there often isn’t a one-to-one correspondence between sounds and letters. “Sh” is actually one sound, not a combination of “s” and “h” – but it’s still represented by two letters, whereas “e” can indicate no sound at all, as in “craze”, which ends phonetically with a “z”. SSP was described with sounds in mind, and doesn’t always work perfectly with letters. I await a version of Wordle for linguistic purists that uses the international phonetic alphabet, but until then, a little bit of phonotactics might still be enough to give you an edge. Good luck!

David Shariatmadari is the author of Don’t Believe a Word: From Myths to Misunderstandings – How Language Really Works