We’re Talking About Vaccines All Wrong

To reach vaccine conspiracists and other skeptics, focus on what they care about most: freedom without repercussions.

So far this year, freshman Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene has outraised all of her GOP colleagues in the House, raking in $4.53 million in the first six months of 2021. (Among congressional Republicans, only Senators Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley have raised more.) Yes, Greene is paying quite a bit to raise those funds, but it remains a staggering amount for an incumbent in a safe red district, especially when most of it has come from small donors. What on earth do people think they’re buying with that money?

One thing her donors are definitely not buying is a coherent political message. Last week, after being suspended by Twitter for 12 hours for falsely claiming that there had been “6,000 vax-related deaths,” she held a press conference in which she repeatedly contradicted herself, arguing at one point that the number was actually higher, while also appearing to agree with her colleague Steve Scalise that the vaccine is safe and effective.

Asked by reporters for her actual beliefs, Greene deflected, embracing instead the mantra of conspiracy theorists everywhere: Do your own research. “I encourage people to make up their own mind,” she said at one point, before echoing a few minutes later the old conspiracy theorist’s standard that someone should be looking into all of this: “You see, there’s a lot of things happening and I think we should analyze all of it before governments and schools and businesses say, ‘Absolutely, you have to take this vaccine.’”

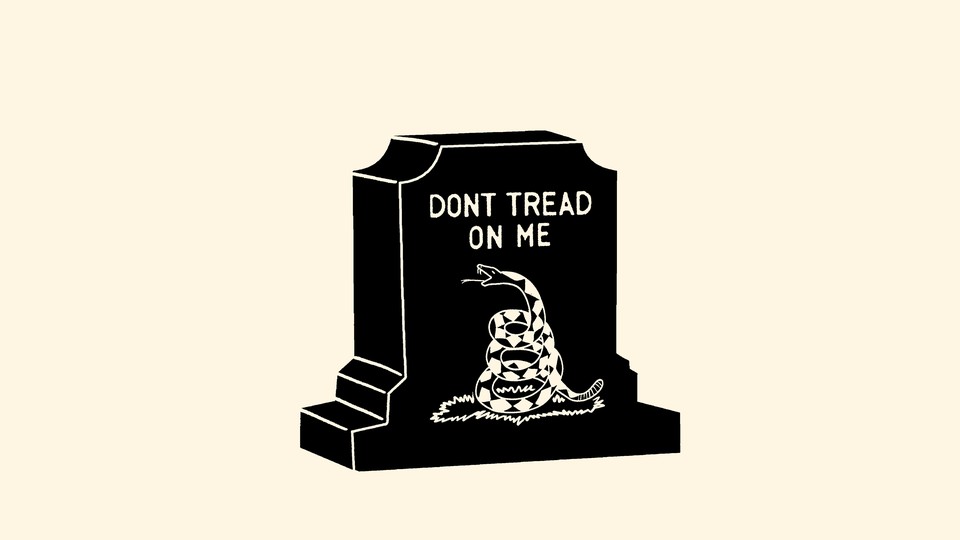

What Greene is offering—and what her supporters are buying—is not an alternative theory but rather freedom: the freedom to disregard acknowledged authorities like Anthony Fauci, and the freedom to come to your own conclusions. Although we tend to think of conspiracy theories as dark, paranoid, and unsettling, for the conspiracist they can be quite liberating, because they free you from having to accept things you don’t want to believe.

Writing about rumor and urban legend in America, the sociologists Gary Alan Fine and Patricia A. Turner borrow a phrase from the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who has said that some ideas are simply “good to think.” That is, we subscribe to some ideas not necessarily because they’re true (or defensible) but because the simple act of believing them brings a kind of reassurance and pleasure. As Fine and Turner note, urban legends and conspiracy theories are good to think because “they connect to a powerful ‘cultural logic’ that makes sense to narrators and audiences. Plausibility is key. Rumor permits us to project our emotional fantasies on events that we can claim ‘really did happen,’ protecting ourselves from the implications of our beliefs.” By rejecting the dominant narrative without providing a substantive replacement, Greene offers her audience the freedom to cherry-pick sources and devise a narrative that best fits their biases, disregarding anything that collides with their worldview.

The historian Philip Deloria once described Americanness as “a particular working out of a desire to preserve stability and truth while enjoying absolute, anarchic freedom.” It is this impulse for irresponsible freedom—embedded within the framework of a stable social-service net—that Greene and her cohorts crave. They want the freedom to not wear a mask with the assurance that they’ll be well taken care of at a hospital if they do get sick. And they want not only their access to the social safety net protected, but also their access to social media and the connection to American culture that comes with it. Greene’s outrage over her Twitter suspension, beyond being an obvious publicity stunt, reflects a genuinely acute anxiety of a movement at a turning point.

One of the most consistent arguments Greene put forward in her press conference is the idea that people who choose not to wear masks or be vaccinated should not be socially ostracized for their beliefs. This gets to the core of the anxiety driving the anti-vax movement: They want all the rights, privileges, and benefits of human community without any sense of obligation to be responsible participants in that community. “I’m going to always be in the camp that it should be people’s choice,” Greene said during her press conference. “I just think we’re going down a really bad road when we’re telling people, ‘You have to do this and if you don’t do it you’re excluded, you’re treated like a second-class citizen, you’re not allowed on campus, you’re going to be fired from your job, we’re not going to let you in church, because you refuse to take this FDA-approved vaccine.’ I just think that it’s the wrong place for us to go as Americans.”

If we can recognize that the real gift Greene is offering is not misinformation so much as it is freedom, we might be able to approach the problem of misinformation differently, particularly surrounding COVID-19 and vaccines. Researchers have known for years that shaming people to get vaccinated often ends up backfiring, and that much of this is because vaccine resistance is heavily correlated with notions of personal liberty. The people we’re trying to reach are not motivated to act on behalf of others, and they won’t respond to exhortations of civic responsibility.

If Greene’s supporters want freedom without repercussions, focusing on consequences for this freedom might give us more leverage than we might think, particularly if we can shift the focus from “freedom versus obligation”—the way conspiracists like Greene prefer to frame the issue—to differing kinds of freedom. Vaccines offer us the freedom to participate, the freedom to circulate back in the world, the freedom to be human again. The Washington Post, for example, reported on one vaccine holdout who got her shot so she could attend New York Yankees games in person. When The Dallas Morning News asked prominent citizens of North Dallas why they got vaccinated, some spoke in terms of obligation and protecting others. But others spoke of the possibilities associated with the vaccines. Robert Jeffress, the pastor at First Baptist Church, echoed Greene’s line at first, stating that “we are not trying to force anyone to be vaccinated—that is a personal choice,” but he went on to say that vaccination is “the quickest way for Christians to come back to church safely so that we can enjoy the encouragement we all need that comes from worshipping together.” It’s a tricky but promising rhetorical move: You can choose to do whatever you want, but the rest of the world is waiting for you if you choose to get vaccinated.

Now, as the Delta variant threatens a fourth wave, more and more public figures have begun to focus on the other half of this equation: increasing the social pressure and repercussions that come with remaining unvaccinated. Disbelief and frustration that anyone would decline to be vaccinated are giving way to pure anger, and businesses, schools, and individuals have run out of patience accommodating those resisting inoculation. New York City has announced that all of its employees (including the vaccine-resistant ranks of the NYPD, only 43 percent of which have been fully vaccinated) must get vaccinated or face weekly tests. California’s statewide university systems have instituted similar mandates, and even the Biden administration is considering a vaccine mandate for all federal workers. Individuals can still opt out, but to do so may mean constant testing and screening, social-distancing and mask requirements, and travel restrictions—the goal being, it seems, to put an increasing social burden on holdouts so long as they continue to endanger others.

Greene will continue to push the rhetorical move that Americans deserve not just freedom but freedom without consequence. On Sunday, she shifted from Holocaust analogies to Jim Crow analogies, tweeting out a photo of a sign reading NO VAX NO SERVICE with the comment “This is called segregation.” But it’s less clear how long this tactic will succeed. Even Alabama Governor Kay Ivey made a distinction not between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated but between vaccine holdouts and “regular folks.” Talking to reporters last Thursday, she lamented that “folks are supposed to have common sense. But it’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, not the regular folks. It’s the unvaccinated folks that are letting us down.”

When Mobile’s Fox 10 reporter Stephen Moody went in search of reactions to the governor’s comments, he mostly found agreement. “I never thought I would agree with Kay Ivey,” a woman named Sabrina Lewis told him, “but I agree. I know it’s a personal choice, but so we can continue to enjoy things like this, people should give the vaccine a try.” For Lewis, as with so many millions of other Americans, vaccines mean freedom—not just freedom to participate in the human community, but also freedom from social stigma. Meanwhile, the only person Moody could find who disagreed with Ivey’s comments would speak out against them only if she could remain anonymous.