Blackface Was Never Harmless

In 1869, an Atlantic writer remembered darkening his face with burnt cork and acting out exaggerated caricatures of blackness with little reflection on the racial oppression and violence around him.

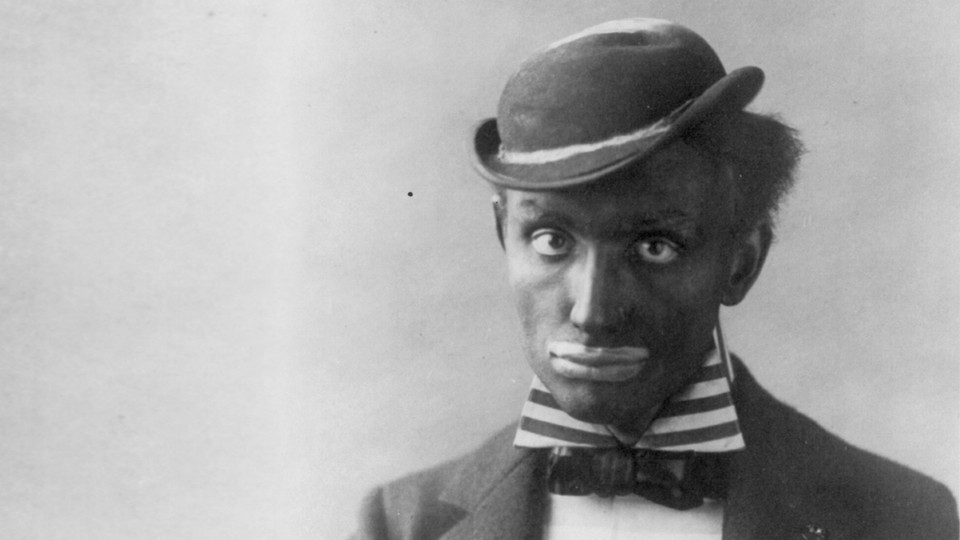

Long before the future leaders of America were moonwalking with shoe polish smeared on their cheeks, the first blackface minstrels took to the stage in the early 19th century. Beginning in the decades leading up to the Civil War, troupes of white men, women, and children darkened their faces with burnt cork and traveled the country performing caricatures of blackness through songs, dances, and skits. These performances, arising out of Pittsburgh, Louisville, Cincinnati, and other cities along the Ohio River, became one of America’s first distinct art forms and its most popular genre of public entertainment.

From the beginning, minstrelsy attracted criticism for its racist portrayals of African Americans. Frederick Douglass decried blackface performers as “the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens.” In venues where black artists were often banned from performing and black audiences, if they were admitted at all, were forced to occupy segregated sections, white entertainers in blackface furthered the same paternalistic and degrading stereotypes that plantation owners and politicians advanced to justify slavery, and helped create a racist symbology that came to represent generations of prejudice. Shows featured a cast of recurring characters: the clownish slave Jim Crow; the obsequious, maternal Mammy; the hypersexualized wench Lucy Long; the arrogant dandy Zip Coon; the lazy, childish Sambo. Some of these archetypes continue to surface in the present day.

“There’s always been a resistance to it, in part because it was so demeaning,” says Lisa M. Anderson, who has studied the history of minstrelsy and other performances of race as a professor at Arizona State University. “The shows really were set up to demean blackness and black people.”

But to many white audiences and entertainers, the performances seemed innocuous, fun, even esteemable in their representation of African Americans. Early audiences were composed mainly of white working-class people and recent immigrants, for whom, Anderson says, the exaggerated characters onstage enhanced a feeling of racial superiority and belonging—and provided cheap, accessible entertainment. The shows reflected back a foolish, animalistic image of blackness that was already ingrained in the national culture; the racism was so familiar to observers that it could be lauded as artistic or progressive, or even overlooked entirely. That indulgent ignorance has followed blackface through decades of criticism and transformation, and into the present day.

Two Atlantic articles from the late 1860s provide insight into minstrelsy’s heyday in the mid-19th century. In an article from our November 1867 issue, Robert P. Nevin describes the form’s early development with an admiration largely divorced from consideration of its sociopolitical context or implications. He viewed successful minstrel performances as accurate portrayals of African American culture and mannerisms, praising their ability to retain “unimpaired … such original excellences as Nature in Sambo shapes and inspires.”

He lamented what he saw as the temporary failure of performers in the 1830s and ’40s to live up to this goal. “The intuitive utterance of the arts was misapprehended or perverted altogether,” he recalled. “Gibberish became the staple of its composition. Slang phrases and crude jests, all odds and ends of vulgar sentiment, without regard to the idiosyncrasies of the negro, were caught up, jumbled together into rhyme, and, rendered into the lingo presumed to be genuine, were ready for the stage.”

But ultimately he devoted his article to praising the songwriter Stephen C. Foster, who began writing for minstrel shows in the 1850s and, in Nevin’s eyes, elevated the performances to a position of new respect. Rather than embodying only “the vulgar notion of the negro as a man-monkey,” Nevin wrote, Foster’s art “teemed with a nobler significance. It dealt, in its simplicity, with universal sympathies, and taught us all to feel with the slaves the lowly joys and sorrows it celebrated.”

During this period of heightened popularity and respect, Ralph Keeler, then an adolescent boy who had fled his New York family, became enamored with minstrelsy and joined a traveling troupe. He described the experience in an 1869 article for The Atlantic, charting his three years as a “youthful prodigy” who performed jigs, played female parts in “negro ballets,” and danced as a “wench” to the misogynistic “Lucy Long” song.

To Keeler, the racial aspect of the performances seems incidental; his article makes almost no mention of the nature of the characters he played or his own understanding of blackness. Instead, he dwells on his development as an entertainer, on the excitement of finding a place in a troupe and traveling the country, and on his eventual disenchantment with playing to an audience. When the social and political dynamics of race do enter into his story, it comes off as more inadvertent than anything. He describes, for instance, a black man named Ephraim who began traveling with and serving the troupe, although he was repeatedly told that it couldn’t pay him for his labor, and who became an object of ridicule before being jailed for an altercation with an Irishman that he didn’t initiate. Introducing him partway through the article, Keeler cruelly describes Ephraim as “one of the most comical specimens of the negro species.”

In a more striking passage, Keeler recounts witnessing a mob lynching a man on a boat while traveling through the Midwest. The troupe arrived in the town of Cairo, Illinois, on the night that a group of white men decided to punish a black man who had been running a “gambling-saloon” on his “old wharf-boat” by the town levee. “At a given signal, the wharf-boat was set afire and cut adrift, and, as it floated out into the current, the vigilantes surrounded it in small boats, with their rifles ready and pointed to prevent the escape of their victim,” Keeler remembers. The minstrels and vigilantes watched as the boat exploded with the black man still on board.

“The next day I spoke with the leader of the band in the small boats,” Keeler writes. “He even confessed that … he felt almost sorry for the victim, after the explosion had blown him into eternity.” Then the article moves on, without further reflection.

Keeler does describe losing respect and enthusiasm for minstrelsy, though not because of any moral objection. Early on, he recalls, “I looked upon a great negro minstrel as unquestionably the greatest man on earth,” but later began “to doubt whether a great negro minstrel was a more enviable man than a great senator or author,” and he decided to leave the troupe to pursue a university education.

Soon after Keeler’s stint in the shows, minstrelsy’s popularity began to decline, particularly in the North. Looking back from 1869, he begins by noting: “Negro minstrels were, I think, more highly esteemed at the time of which I am about to write than they are now; at least, I thought more of them then, both as individuals and as ministers to public amusement than I ever have since.”

But despite consistent resistance to the racist portrayals and the rise of more popular art forms, blackface performances persisted, becoming a part of vaudeville shows, radio programs, and television shows and movies as time went on. Only in the late 1940s and early 1950s, with increased public pressure from the civil-rights movement, did the form mostly disappear from stage and screen. But even then it remained a part of the national culture, a feature of parties, Halloween costumes, comedy sketches, and fashion that’s lingered on into the 21st century.

In part, Anderson says, white Americans might continue to wear blackface out of ignorance. “People don’t necessarily know the history of blackface minstrelsy,” she says. “They don’t necessarily even know that was a thing. They’ve seen blackface images, but they don’t know that’s where they came from. So there’s a kind of decontextualization of the place of blackface in our history.”

But in some cases the choice seems to go beyond ignorance. The photo of two men standing side by side in blackface and a Ku Klux Klan robe, respectively, that appeared in Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s medical-school yearbook (without his knowledge, he now claims), is difficult to explain away by saying its racist implications were unclear; even if blackface has been decontextualized, the KKK robe remains unambiguously attached to the tradition of white supremacy that spawned it. And Virginia’s attorney general, Mark Herring, said in a statement about his own youthful experiment with blackface that it was “a minimization of a horrific history I knew well even then.”

That horrific history can also be traced as a legacy of white ignorance, from the 1860s articles that fail to grapple with minstrelsy’s racial context and implications to the statements of frat boys and medical students and police officers who appear in blackface in photos that continue to crop up in the news now. But against a backdrop of consistent criticism and overt racism, some of that ignorance, then and now, appears willful—and some of it doesn’t appear to be ignorance at all.