Roughly half of runners go through a series of mental calculations before lacing up. In addition to considering their distances and splits, female runners go through a complex checklist before they head out. How many minutes of daylight remain, how easy their keys are to reach in an emergency, who they should inform of their running route, whether it’s safe to wear headphones and whether they’ll get to the end of their run without feeling afraid. For far too many women, running isn’t the cherished slice of personal time it should be or the endorphin-filled escape it sometimes can be.

Instead, they run on their guard, looking over their shoulders, bracing themselves against a constant threat of vocal or physical harassment. That’s why, together with our sister magazine, Women’s Health, we at Runner’s World are launching the Reclaim Your Run campaign, the aim of which is to raise awareness of, and reduce, the harassment and endangerment women experience while running.

The problem is widespread: in a new survey of over 2,000 runners by RW and WH, 60 per cent of women said they had been harassed when running, 25 per cent reported being regularly subjected to sexist comments or unwanted sexual advances and six per cent said they had felt threatened to such an extent by harassment while running that they feared for their lives.

The impact is hugely damaging, negating the physical, emotional and mental benefits running offers, and often denying women the very act of running itself – 11 per cent told us they had stopped running because of harassment.

Responding to our survey, hundreds of female runners shared their experiences of harassment and how it has affected their running and their lives. For runner and anti-harassment activist Cat Roberts, the issue came sharply into focus last year. ‘It’s not new information that when you’re heading out as a woman you expect to get heckled,’ she says, ‘but at the beginning of the first lockdown I was running every day and I was experiencing incessant catcalling and wolf-whistling. The traffic-free streets should have been liberating, but I was constantly on edge. And I just got tired of being wary every time I laced up my shoes.’

Roberts’ experiences led her to contact other women and share their harassment stories on her website and to begin campaigning against street harassment of runners. ‘I started talking to other women, who told me, “Yes, I’ve had similar experiences, but what can you do about it?”.’ I just thought that we shouldn’t have to put up with this.’

Street harassment is not something suffered only by runners, but runners do seem to be particularly at risk. ‘I was surprised by how much it affected the running community,’ says Roberts. ‘Of course, it shouldn’t be the case, but it may be that by moving our bodies and putting ourselves out there, some people deem that an invitation to comment on us.’

That toxic assumption is only one among many factors that leave female runners vulnerable. ‘There’s also the fact that people often run alone and if perpetrators see people by themselves, that increases the likelihood,’ says Amber Keegan, a campaigner at Our Streets Now, a movement fighting public sexual harassment. ‘And as, when you’re running, it’s desirable to avoid other people, you’re more likely to be in less public spaces, which puts you in an environment where you are more vulnerable.

‘Also, the fact that you’re running means potential perpetrators know that you are going to be out of their line of sight fairly quickly, so they may feel that they don’t really have to confront what they’re doing.’

Culture of fear

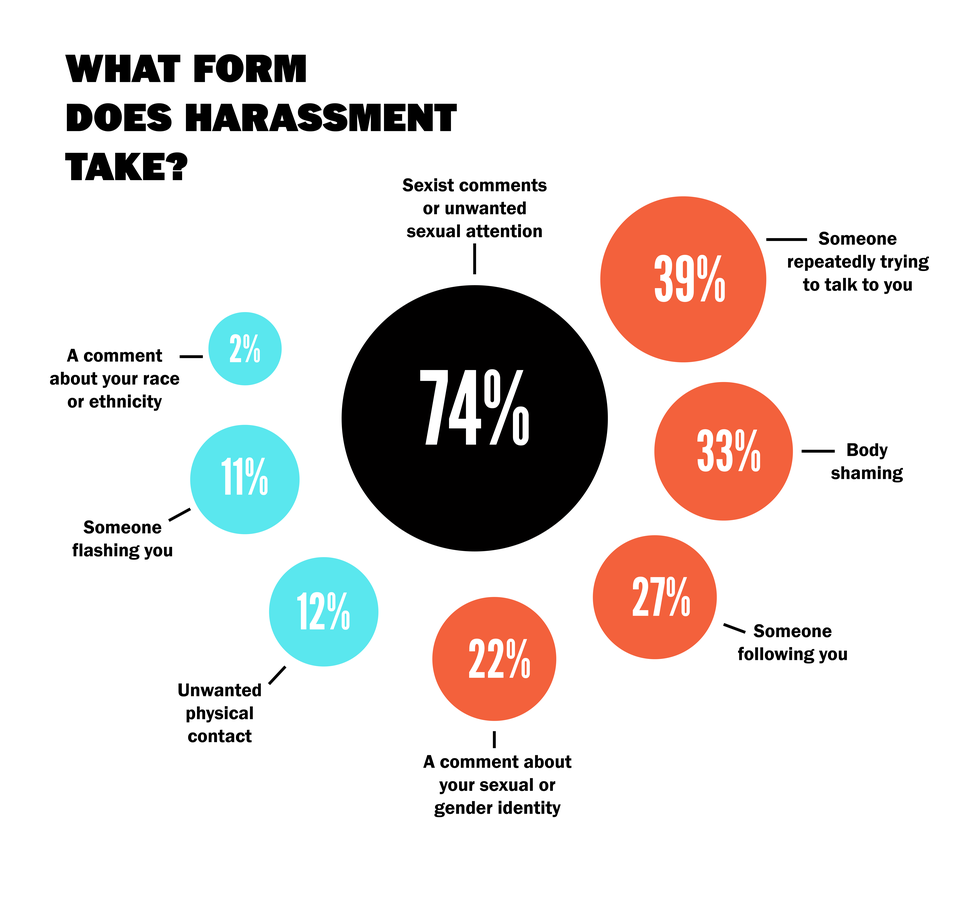

Harassment takes many forms, but the most common category reported in our survey was sexist comments or unwanted sexual attention, with 74 per cent of women who have been harassed experiencing one or the other. Also common are body shaming or insults about appearance, which 33 per cent of women reported. This verbal abuse falls under the realm of public sexual harassment, but, disturbingly, our survey also highlighted the prevalence of more severe and intrusive forms of harassment, with 39 per cent of women having experienced someone repeatedly trying to talk to them, 26 per cent someone following them, 11 per cent someone exposing themselves and 11 per cent someone making unwanted physical contact.

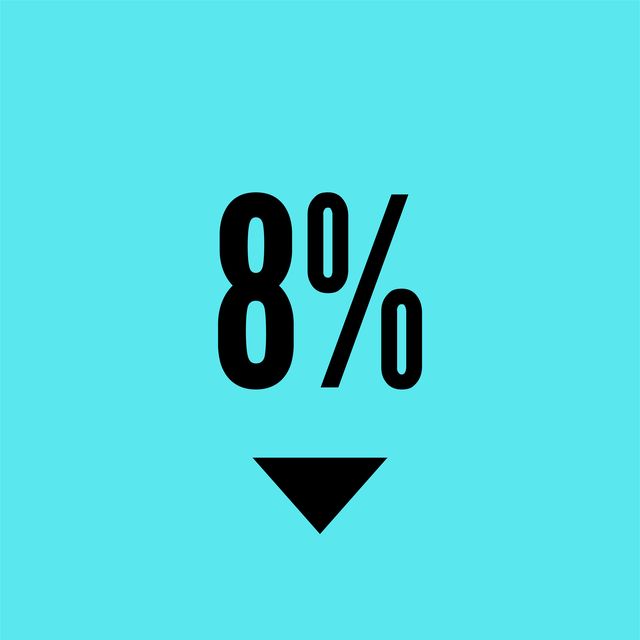

The fear women feel on the run is real and pervasive. In our survey, only 13 per cent of female respondents said they have never feared for their safety when running, eight per cent fear for their safety on most runs and two per cent experience such fear on every run.

Even when an incident doesn’t go beyond a verbal comment, the fear of escalation – of a chain of events that leads to physical assault – weighs heavily. ‘Once you have had it escalate, or you know of someone it has escalated for, then that fear is there, it doesn’t just go away,’ says Keegan. ‘It’s a survival instinct, it’s there to protect you, but it shouldn’t have to be.’

This is something Emily Buchanan, a 41-year-old mum of two from Yorkshire, knows all too well. ‘I took up running five years ago,’ she says. ‘With two small boys in the house, I loved the headspace and sense of freedom it gave me. But within months, I understood why so many women associate it with a sense of threat. I was running alongside a main road one morning, when a van slowed down until he was just ahead of me; he kept slowing so he was close to me and I could see he was masturbating.

‘Feeling sick, and vulnerable, I changed my route to loop back home, but he followed me. Adrenaline-flooded and heart pounding, I sprinted the few minutes to my front door.

‘It was months before I felt ready to go out for a run alone. I gradually built up my fitness before signing up for a 10K and, after that, a half marathon; I was determined not to let that incident rob me of my hobby.

‘When men shout at me about my appearance while I’m running or try to talk to me, it doesn’t really bother me. But when a man passes me in the street on his own, I feel frightened. I now forgo blasting my playlist through my headphones so I can stay alert.’

Though she hasn’t suffered an experience as shocking as Buchanan’s, Roberts stresses that verbal or less severe physical acts cannot be disconnected from more serious and even violent acts. ‘I’ve experienced physical harassment; for example, when a cyclist rode past and grabbed my bum,’ says Roberts. ‘It can be stuff that doesn’t seem outwardly violent, but it really perpetuates the idea that women’s bodies – and especially female runners’ bodies – are there to be used. In my experience, and in that of many of the women I’ve spoken to, the harassment is generally verbal; however, we have to ask ourselves, if we allow verbal abuse, how much is that going to become a gateway into other abuses – maybe physical abuses and more violent abuses?’

Others agree that tolerance of what may be classed as minor acts of harassment provides a dangerous pathway to more serious offences. ‘There’s a false impression that there are some moments when you can do this,’ says Georgie Laming, campaign manager at Plan International UK (plan-uk.org) which, having conducted extensive research into public sexual harassment, has drafted a bill to make it a criminal offence. ‘When a woman is dressed up for a night out, for example, or out running, there’s this assumption that she wants attention paid to her, but there’s a difference between a compliment and harassment. And that’s where it’s really clear that there’s a link between harassment and gender-based violence –that the harassment comes with a theory that there is some sort of implicit consent from women and that’s just absolutely not true.’

And for victims, assessing the threat carried in every intrusive act is exhausting and distressing. ‘You can see from the recent outpouring on social media that you never know when someone is just making a “cheeky comment” or when it could go further,’ says Laming. ‘And it’s particularly difficult for women to have to judge a situation in a moment when they are likely to be on their own and quite vulnerable.’

Freedom curbed

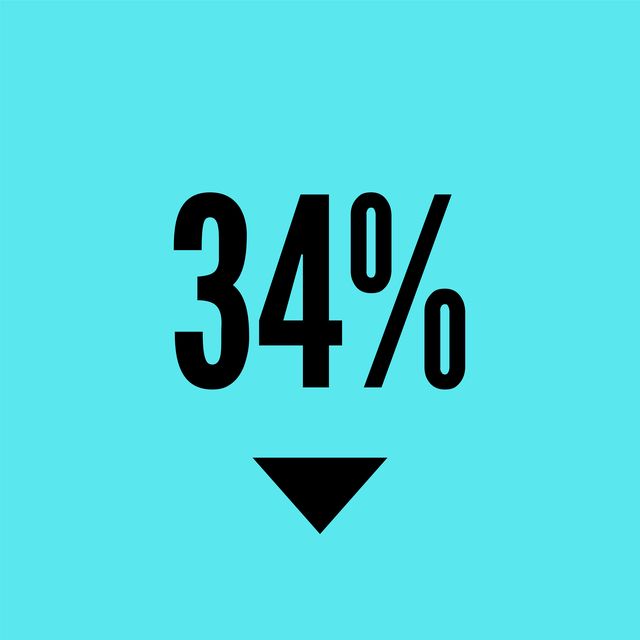

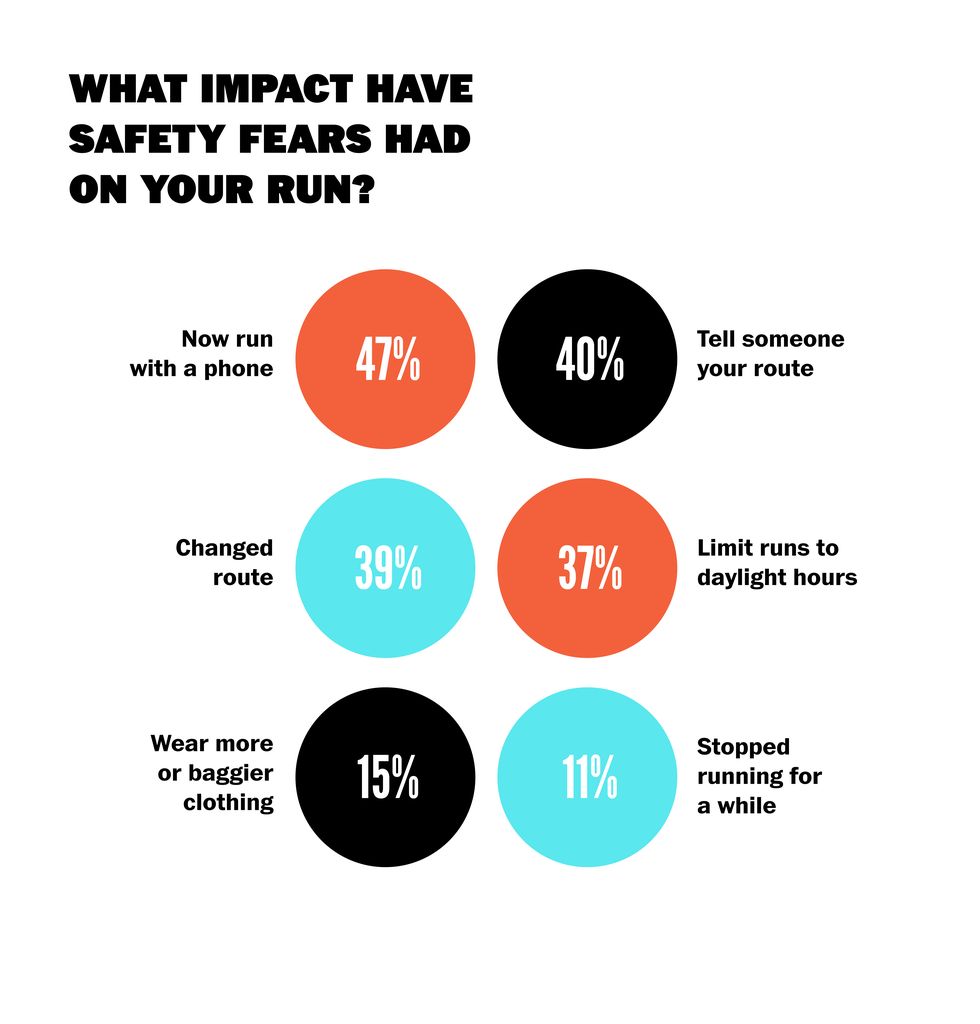

This ever-present spectre of harassment undoubtedly limits women’s freedom to run when, where and how they want to. In our survey, of those women who have questioned their safety or felt uncomfortable on the run, 91 per cent have changed their behaviour in some way as a consequence. Only eight per cent told us they will run whether it’s light or dark outside, while 39 per cent have changed routes, 30 per cent now avoid a place where they used to run (owing to safety concerns) and 10 per cent have switched to running on a treadmill rather than outside. And it doesn’t end with time and place: 47 per cent now run with a phone, 16 per cent use safety-tracking apps, 40 per cent inform someone of their route, 21 per cent no longer run alone, 15 per cent wear more or baggier clothing and two per cent have taken self-defence classes.

After a series of threatening encounters, Bryanna Gondeiro-Petrie changed her running habits completely. One particularly disturbing incident occurred when she was out for an early morning run on a road with light traffic, and noticed a black car speeding towards her. Abruptly, the car slowed down. Then the driver rolled down the window. Gondeiro-Petrie vividly recalls his ‘evil grin, as if he hit the jackpot in finding me’, she says.

The road behind Gondeiro-Petrie was empty – no houses, no cars, no side roads and nowhere to go. About a quarter of a mile ahead, she saw an older gentleman watering trees on his drive. She thought, ‘I need to get to that drive.’

As she sprinted past the car, the driver opened the door, yelled something unintelligible and laughed. He then hit the accelerator, U-turned and drove down the wrong side of the road, coming up fast behind her. The driver then parked at the side of the road and watched her until she reached the man watering the trees; only then did he finally speed off.

Though she still runs, Gondeiro-Petrie’s relationship with running has changed significantly. She stopped trail running. She became more intensely aware of her surroundings, watching passing men and cars with a hawk’s eye. She frequently changes up her routes, sometimes even midrun, if something feels ‘off’. She hatches just-in-case escape plans. ‘I never imagined I wouldn’t feel safe running by myself,’ says Gondeiro-Petrie. ‘There are days when I feel like I can’t even enjoy myself because I’m on edge.’

These limits on running freedom and enforced safety measures are the norm for countless female runners and were brought into sharp focus in March this year for 29-year-old Caitlin Sullivan. ‘I work in Clapham and run through the area multiple times per week, so Sarah Everard’s tragic death resonates acutely,’ says Sullivan. ‘Street harassment is a normal occurrence for me. I once hid behind a tree to check someone had gone before continuing my run; I’ve changed direction and even sped up to avoid men. A few months back, a van pulled up behind where I was running and the driver asked if I wanted to get in the back.

‘As a teacher, I start work at 7:30am, so I tend to run in the evenings – but I no longer run in the dark. I’ve switched my long-run routes so they’re now in busier parks and I’ve set up safety features on my fitness tracker so my friends and family can track where I am. These changes make me feel safer, yet I resent them; the onus shouldn’t be on women to keep ourselves safe.’

It’s not just the running experience that is affected; this heightened level of anxiety also exacts a mental toll that can wedge its way into non-running hours. ‘People minimise street harassment, but it acts like toxic fumes that seep into the psyche,’ says Dr Joan Cook, associate professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, US.

According to a study by the charity Stop Street Harassment, of those who experienced harassment or assault, 30 per cent of women reported anxiety or depression. And those women may even exhibit signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, says Stop Street Harassment founder Holly Kearl, heightening feelings of vulnerability, affecting sleep and making it harder to focus at work and home.

That the stress-relieving, mental health-enhancing benefits of running are compromised by harassment and its expectation is also a major issue, one that’s been felt particularly keenly over the last year. ‘Exercise has made a huge difference during the year of restrictions and, for women, that has been denied to a certain extent,’ says Laming. ‘Women can’t just switch off when doing exercise; they are constantly vigilant.’

Moving targets

While all women are at risk, certain groups are more likely to be targeted and to have another element of their identity brought into the harassment. ‘Our research shows the intersectionality element,’ says Keegan. ‘It’s more likely to happen to someone who

is also black, or who is also disabled in some way, or is also LGBTQ.’ Laming agrees: ‘We know that sexual harassment has that intersectional angle. If you’re a woman of colour, for example, then not only will you get sexually harassed, it’s likely to have a racist element; or if you’re a disabled woman, it will have that element to it.’

Intisar Abdul-Kader understands how it feels to be subjected to this combined sexual and racial harassment. ‘I got into running 10 years ago and now run three to four times a week,’ says the 34-year-old. ‘I’m Muslim, and my faith is obvious because I wear the hijab – I’ll also wear long sleeves and if I’m wearing running tights, I’ll wear a longer top that covers my hips. Last summer, a man yelled, “I’m sure your God would allow you to show some skin and hair! It’s hot and you’re hot.” The simultaneous racism and sexism completely threw me and left me feeling exposed.

‘The catch-22 that women find themselves in is infuriating: you get blamed for harassment if you don’t wear much, but are still shouted at when you’re covered up. Meanwhile, men run in shorts all the time and no one comments.

‘Despite my anger, I’ve never shouted back or reported harassment. But I think that’s because I’m more concerned with my safety than correcting their behaviour. I try my best to run in daylight and If I do run at night, I stick to busy, well-lit streets and wear clip-on lights on my shoes; I always tell my family my route and when roughly to expect me back. Do I think it’s fair I need to do these things? No. But I’m determined to continue running – it’s an act of defiance.’

Harassment can affect runners at all levels of experience and ability. Earlier this year, a group of elite athletes – former Wales 400m champion Rhiannon Linington-Payne, Team GB and Wales sprinter Hannah Brier and 400m hurdler Lauren Williams – spoke out about the harassment they had received while training in public spaces. And Team GB 1500m runner Sarah McDonald was left in a ‘state of shock’ after a man on a moped grabbed her backside when she was training on a canal-side path in Birmingham.

While these athletes and millions of seasoned ‘everyday’ runners such as Abdul-Kader find the strength to keep lacing up despite their experiences, harassment can be even harder to overcome for new and less confident runners. As Cat Roberts says: ‘As this came to my attention during lockdown, when a lot of people had just started running, I thought, I’m not a new runner, I’m confident and it’s making me reluctant to go, so what’s it doing to people who are just starting and just finding the confidence to go out?’

Indeed, the way many women change their behaviour in response to harassment is simply to stop running altogether. Our survey may not have reached all those would-have-been runners, but we know there are far too many of them. ‘A lot of women and girls have been in touch with me to say that they didn’t like running because it was intimidating and people shouted at them,’ says Keegan. ‘It’s a horrible barrier to participation and dealing with it is such an important part of getting women and girls running and keeping them running.’

‘For new runners, it’s a huge hurdle – all it takes is one bad incident and that person may not run again,’ agrees Laming, who can draw on her own experience. ‘I don’t run anymore and that’s why. I was new to running, doing the Couch to 5K plan in my local park, but every time I went out I would have quite gross sexual comments shouted at me. I just couldn’t do it anymore.’

Changing the narrative

So how can we create a runners’ world where all have the freedom to run without fear? From your passionate and informed feedback in our survey, plus insight from those campaigning for change, it’s clear that we need to shift the narrative from looking at what women must do to protect themselves, to addressing the behaviour of the perpetrators.

‘Every time I run down the main road near where I live, I’m beeped at, or heckled, or wolf-whistled roughly every 500m,’ says Roberts. ‘Some people will say, “Stop running there, you know it’s a hot spot,” but it shouldn’t be on women and other marginalised genders to modify their behaviour in order to not be a victim.’ Roberts stresses how deeply entrenched this onus on women to self-protect is in our culture: ‘We’re all told when growing up to not wear “provocative clothing” and that it’s our responsibility to keep ourselves safe, rather than the responsibility of the people who are harassing us to not harass us.’

Laming agrees that shifting the focus is fundamental to meaningful change. ‘Women already know what to do to make themselves safer; it’s been ingrained into them,’ she says. ‘Our research with parents shows 80 per cent fear their daughters will experience public sexual harassment in their lifetime [with 67 per cent instructing them not to walk home after a certain time]. Girls and women have had these tactics forever, but having pepper spray or a rape alarm hasn’t changed anything, so we need to change tack and not think that running with our keys in our hands is going to change anything.’

We must also recognise that we need to look outside running to solve the problem of harassment on the run. In our survey, only four per cent of women who had been harassed reported the harassment as coming from other runners, 67 per cent of women reported being harassed by someone driving a car, 59 per cent by someone driving a van and 45 per cent by someone walking with others.

The events surrounding the death of Sarah Everard earlier this year [a police officer has been charged with kidnap and murder] brought the issue of women’s safety in wider society to the fore, while statistics from a survey by UN Women UK, which revealed 80 per cent of women reported experiencing sexual harassment in public spaces, illustrate how pervasive the problem is.

‘I speak about it as a runner, but, of course, it goes deeper,’ says Roberts. The issue, according to Roberts and many others is that sexual harassment has been trivialised, normalised and accepted for too long. ‘It’s expected in society that this lad culture is normal and OK,’ she says.

‘It’s a social norm,’ agrees Keegan. ‘Our research into different age groups highlights that if I was to ask my mum or my grandma, they would simply accept it

as just something that happens. I think that’s why the problem has flown under the radar for so long; it’s become this ingrained part of society that men think they have to shout after women.’

Even the language used around the issue is loaded to minimise the significance of the acts, says Keegan. ‘We feel phrases like “wolf-whistling” and “catcalling” are belittling and almost demean the issue,’ she says. ‘The term public sexual harassment makes the link to other forms of harassment – such as workplace harassment and more severe forms of violence against women and girls – clearer.’

One element of the culture shift is changing some women’s mindset, so that they no longer see sexual harassment as something that must be accepted. ‘You have women and girls who know the problem exists, but haven’t necessarily been told that it shouldn’t happen to them,’ says Keegan. ‘So one aspect of raising awareness is reframing it to tell those people that it’s not OK and something can and should be done about it.’

‘We would encourage people to really think about the impact it has on them,’ says Laming, ‘and think about all the things they’ve done to protect themselves over the years. In fact, our original anti-harassment campaign was called, simply, It’s Not OK.’

Call and response

Of course, not accepting harassment doesn’t necessarily mean challenging your harasser. ‘I’m kind of an ambassador for being vocal and standing up and getting angry about it, but your safety is the most important thing and if you don’t feel comfortable confronting a harasser, absolutely don’t,’ says Roberts. ‘There are other people who can do that work when it’s safe to do so.’

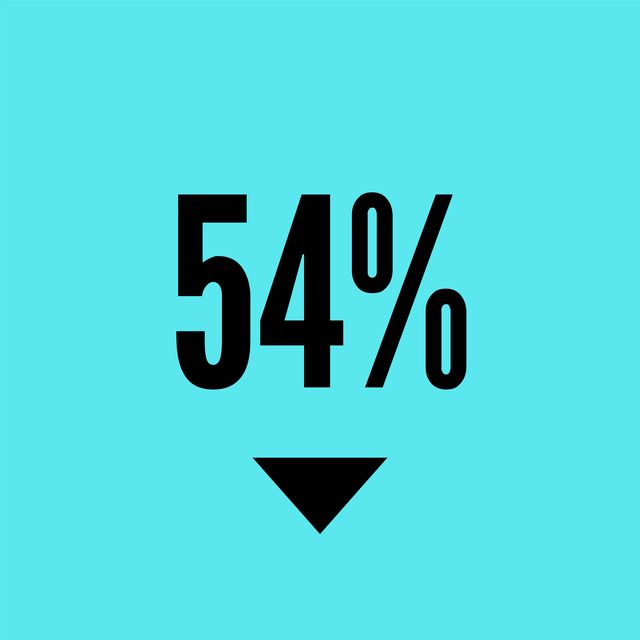

According to our survey, avoiding confrontation is the most common immediate response from women in the face of harassment: 48 per cent of women said they ignored it, 37 per cent ran faster and 23 per cent changed route to avoid further harassment, while only 15 per cent said they had yelled back at their harasser.

This is hardly surprising, considering the perceived threat of escalation in victims’ minds. And it was this threat that shaped 46-year-old Natalie Mitchell’s reaction when she overtook a male runner one Saturday morning. As she passed, he screamed profanities at her. He then sprinted past Mitchell while continuing to gesture wildly in her direction. Mitchell was scared. ‘If this guy tried to attack me, I had nothing to protect myself,’ she says. ‘You hear about a normal woman who goes for a run and doesn’t come back. I have three kids to think about. I can’t risk that.’ She said nothing and finished her run keeping a wide berth behind him.

Sometimes, when situations do escalate, fighting back may become essential, as was the case for Kelly Herron. Her attacker was hiding in a public toilet when she stopped on her run in Seattle, US. She fought back, trapping her assailant until the police arrived. After the assault, she became an activist and founded Not Today. The organisation’s T-shirts display the GPS recording of her assault and the words she shouted at her attacker: ‘Not today, motherf@#!er’.

‘Since my attack, I’ve helped show other women that we don’t have to take abuse and harassment,’ says Herron. ‘We can fight back and we can continue to do the things we love without being afraid. I don’t want to live in a world where women can only run on a treadmill. I want us to be as free as men are to run at night or early in the morning and to feel safe. My message is: prepare for the worst-case scenario, train your mind and your body, and then do what makes you happy.’

There are other ways to fight back. Our survey revealed only three per cent of women who had been harassed have reported it, with lack of trust in police and the assumption nothing would be done commonly cited as reasons for keeping quiet. But reporting is a crucial part of mapping the true scale of the problem and building impetus for action. ‘So much has gone unreported for so long because there’s no real mechanism,’ says Laming. ‘It’s another reason why we need legal change, because until women feel comfortable reporting it and feel it will be actioned, we will never truly know the scale of the problem.’

Roberts also stresses the importance of reporting incidents to the police: ‘Data is our friend in this – the more we report these situations, the more of a map we build up, and the more the authorities will recognise the problem and where it’s best to tackle it,’ she says, while pointing out other ways to share and document. ‘Be vocal about your experiences. The more we talk about it, the less stigma there will be and if we know there are people around to support us, more people will come forward. So document your experiences using apps like Safe & the City, or even just talking about it online – just let people know that this is happening.’

Social media increasingly seems to be a space where women are starting to feel safe talking about harassment, becoming an avenue for women to reclaim their experiences and nudge the conversation forward. ‘Every time I open up the internet, there’s a new story about people reporting street harassment,’ says Roberts. ‘But it’s not that it’s happening more, it’s just that victims are becoming more comfortable speaking about it.’

This social media solidarity is encouraging. But it’s not enough. Women deserve a safe and supportive environment in real life, too. And much of the work needed to make that happen must be done by men.

A runner's alliance

Unsurprisingly, our survey confirmed harassment on the run is overwhelmingly perpetrated by men, with 90 per cent of women reporting men were responsible. A huge shift in male attitudes is needed, and that starts with men understanding the true impact of their behaviour. ‘Often, the intent isn’t to harm or to scare people, but that doesn’t mean that isn’t the impact,’ says Laming.

This goes back to the perceived threat. ‘I think there’s often a complete lack of understanding from the perpetrators,’ says Keegan. ‘Women, girls and other marginalised genders have experienced harassment time and again, along with more violent incidents or attempts to escalate that harassment. When someone shouts a comment from across the street, they don’t see the chain of events that person may have experienced before, or might fear, with good reason. The returning line when you bring this up is, “It’s a compliment,” but it isn’t a compliment; it’s a power move and it intimidates.’

‘It’s why we need legal change,’ says Laming, ‘because it needs to be focused on the impact on the victim rather than the intent of the perpetrator. Someone could say it’s just flirting going wrong, but women aren’t consenting to this behaviour and they shouldn’t have to cope with it and judge the seriousness. They should know they can report it. Cultural change and legislative change are two sides of the same coin and people need to be made aware of the whole range of actions that come under public sexual harassment and how they make someone feel – a “funny” comment in the park may feel fine to the perpetrator, but, actually, you have got someone worried about their safety.’

If you’re a male runner you may already be aware of this, but you can do much more than simply not be a perpetrator. One step is to spread the message. ‘It’s so important to discuss these issues with people in our lives whom these conversations might not reach,’ says Roberts. ‘It’s all well and good being in our own echo chamber, where we recognise this problem in the running community and want to fix it, but not everyone is privy to this information, so pulling up a chair for them and saying, “Listen, this behaviour is not OK and here’s why” is going to make such an impact.’

And if you witness incidents of harassment, be an active bystander. ‘Any small act of intervention is going to, hopefully, help keep the victim safe, and also dissuade that perpetrator from committing similar acts in the future,’ says Roberts. Kelly Herron echoes the safety point: ‘If you run under a bridge and see a creepy guy and you see a woman running toward that bridge, give her a heads-up to go another way.’

There’s also the positive impact intervention can have on both the victim’s sense of safety in the moment and in their reaction to the experience. ‘The second you have someone around you who is with you, it’s incredibly empowering and reassuring,’ says Keegan. ‘And to have someone stand up for you is an incredibly positive experience. I don’t want to say it restores your faith in humanity, but it’s a very positive supporting action coming out of what’s obviously a negative one. Especially for people who are newer to running – imagine if that initial experience wasn’t just one of having abuse shouted across the street…if you have someone standing up for you, it can really change the way you experience that.’

Challenging harassment also helps in the wider sense of redefining what is acceptable behaviour. ‘You’re contributing to that wider cultural change,’ says Keegan. ‘Public sexual harassment only happens because the people who harass have been led to believe that it’s normal and they aren’t going to be challenged for it.’ Laming agrees: ‘When people start calling out behaviour, it changes things,’ she says. ’It’s not just about “cross the street to make a woman feel safer”, as you’ll see in the media; it’s more than that. Calling out behaviour will make a real difference.’

Of course, judging how to intervene effectively – and safely – can be difficult. ‘I’ve had an overwhelming amount of support from men saying, “I want to help, but I don’t know the best way to do it”,’ says Roberts. ‘I’ve had messages saying, “I’ve got kids and I can’t put myself directly in harm’s way, but I want to be able to help, so what can I do?”.’

Laming believes criminalising public sexual harassment will help here, too. ‘It’s been difficult before because if it’s seen as a bit of a laugh, it’s hard to challenge that,’ she says. ‘That’s where the legal change can come in – having it really clearly enshrined in law that it is not OK will bring the cultural change with it.’

It seems clear this legal change – the criminalising of public sexual harassment, for which Plan International UK and Our Streets Now have been campaigning, through their #CrimeNotCompliment campaign – could underpin positive change in various ways. Along with encouraging bystander intervention, it will increase reporting, potentially change the attitudes of perpetrators and drive the culture shift towards no longer accepting harassment. This issue is bigger than running, but unless change happens in wider society we won’t see an end to the harassment of runners and we want to add running’s voice to the call for that change.

That’s why, together with our sister magazine, Women’s Health, we’re inviting you to Reclaim Your Run. We’ll be working with women’s rights advocates, anti-harassment campaigners, athletes and runners like you, to build pressure to make street harassment a crime. We believe it’s another important step we can take to make this a better runners’ world.

What can you do?

Show your solidarity

Stand with the 25% of women who are routinely sexually harassed while out running by heading out yourself for 25 minutes and posting about your run on Instagram using #reclaimyourrun, tagging @runnersworlduk and @womenshealthuk. You can share your distance, your time, a gorgeous view or a sweaty selfie – anything that expresses your support.

Make change

Right now, public sexual harassment isn’t punishable by law. We believe, to make running– and, indeed, public spaces generally – safe for women, this needs to change. That’s why we’re backing the Crime Not Compliment campaign from Our Streets Now and Plan International UK, which aims to do just that. To add your name to the campaign, get details on how to email your MP and find out more, visit plan-uk.org/crimenotcompliment.

Finally, click here to find out more about our Reclaim Your Run campaign.