Move over Sherlock: the radical edge to Enola Holmes

The prolific sleuth's young sister takes centre stage in a new Netflix film and gives us a timely reminder of the hard-won battle for the right to vote, writes Clare Clarke

Arthur Conan Doyle's literary estate is displeased with Enola Holmes, the new Netflix movie adapted from a six-book series by Nancy Springer which stars Millie Bobby Brown as Sherlock's sister. Being displeased is not an unusual state for the Doyle literary estate, a private company owned by Doyle's distant relatives and US literary agent.

In 2014, the famously litigious company lost the copyright to Holmes' stories written before 1923 (retaining copyright on a mere 10 stories).

The Doyle estate maintains its iron grip on those precious 10 tales and alleges that there is a profound and copyrightable difference between those and earlier stories.

The difference, it claims, is that in those final 10 stories, Sherlock has emotions. These emotions are the basis for a lawsuit launched in June, with the Doyle estate suing Netflix, Penguin Random House and Nancy Springer for copyright infringement.

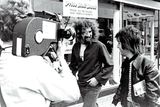

The Holmes siblings: Henry Cavill, Sam Claflin and Millie Bobby Brown in Enola Holmes

Because the Holmes depicted in Enola Holmes has "connection and empathy", he is apparently representative of the character featured only in Doyle's last 10 stories. An unfeeling Sherlock is in the public domain, but an empathetic Holmes is subject to copyright.

Tracing the emotional history of Sherlock Holmes? The game is afoot. Doyle was famously ambivalent about his mythopoeic creation. At the height of the character's fame, in The Final Problem (1893), Doyle killed Sherlock. But Sherlock remained alive in popular culture.

A few months after his death, the first play starring Holmes, Under the Clock, debuted at London's Royal Court Theatre. Since then, along with Dracula and Frankenstein's monster, Holmes has become one of the most adapted characters in literary history.

In 2012, the Guinness Book of Records announced that Holmes was the most portrayed human character in film and television - clocking in at 254 screen depictions.

We might say that there is no such thing as one stable version of Sherlock, instead there are many Sherlocks. Who 'your' Sherlock is tends to be generational. For me, Sherlock is Jeremy Brett. For others he will be Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch. Either way, adaptations keep characters alive that might otherwise die. As Linda Hutcheon observes in A Theory of Adaptation, "an adaptation is not vampiric: it does not draw the lifeblood from its source and leave it dying or dead… It may, on the contrary, keep the prior work alive, giving it an afterlife it would never have had otherwise".

Doyle seemed to realise that adaptation would keep Sherlock alive: when American actor William Gillette contacted the author to enquire whether he might use Holmes in a stage adaptation, Doyle readily agreed.

The Holmes to which the reader of A Scandal in Bohemia is introduced is an emotionless thinking machine. Watson describes him as, "the most perfect reasoning and observing machine… Grit in a sensitive instrument, or a crack in one of his own high-power lenses, would not be more disturbing than a strong emotion in a nature such as his". And yet, in this story, Irene Adler, subsequently referred to as 'the' woman, decalibrates Sherlock's sensitive instruments to the extent that he requests only her photograph as a fee. In Gillette's adaptation, he intensified these softer passions with Doyle's permission. When he asked whether Holmes could marry Adler, Doyle replied: "You may marry him, murder him, or do what you like to him."

Throughout the early Holmes stories, then, Sherlock was not, as the Doyle estate claim, without emotion. Aside from his tenderness towards Adler, he frequently expressed "connection and empathy" as fraternal concern for young female clients.

In A Case of Identity, Holmes declares a brotherly instinct to punish the man who has misled his naïve step-daughter: "If the young lady has a brother or a friend, he ought to lay a whip across your shoulders."

In The Copper Beeches, when governess Violet Hunter comes to him with concerns about a dangerous-sounding job, he remarks: "It is not the situation which I should like to see a sister of mine apply for."

In Enola Holmes, Sherlock evinces the brotherly concern which was already apparent in these stories, growing to 'connect' with his sister: "[I find] you quite extraordinary," he admits near the film's close. And yet, this is emphatically not a story about Sherlock and his emotions.

The story opens when Enola's mother Eudoria (Helena Bonham Carter) vanishes on the day of her daughter's 16th birthday. With that disappearance, Enola becomes truly 'alone' - the anagram of her name with which her cypher-loving mother anointed her.

Her brothers Mycroft (Sam Claflin) and Sherlock (Henry Cavill) are summoned with the dual purposes of finding their mother and dealing with the 'wildling' child who has been brought up on a radical diet of archery, jujitsu, Mary Wollstonecraft's proto-feminist writings, and - worst of all - running around unfettered by a proper corset.

For the conservative Mycroft, boarding school will train Enola to become the kind of lady who will attract a husband. When Enola exclaims, "I don't want a husband!" Mycroft replies, "that is another thing you need educated out of you". "You're being emotional," Sherlock tells Enola, "it's understandable but unnecessary."

The film looks sumptuous, conjuring a Victorian world of steam trains, glistening cobbled streets, and newspaper vendors. Fleabag director Harry Bradbeer freshens this traditional approach adding playful visual touches, including delightful stop-motion animations of anagram tiles rearranging themselves as Enola puzzles out cyphers. Sidney Paget's illustrations for the Holmes stories appear with Cavill's chiselled face transposed on to Sherlock's body.

The train-carriage shot of Enola's escape strongly evokes one of Paget's most famous images of Sherlock aboard a train in The Silver Blaze. There is also a jaunty direct access narrative by Enola, who frequently breaks the fourth wall to speak to the audience. Despite their shared interest in feminism, Enola's narrative is not in the painful confessional style of Bradbeer's Fleabag - this is something more akin to a playful Ferris Bueller's Victorian Day Off.

Enola's search for her mother soon gives way to her involvement in the case of a runaway teenage Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge), whose vote is crucial to the passing of the latest Reform Act. The Act will see franchise extended to working-class men.

The action-packed narrative inverts traditional Sherlockian gender roles, seeing a brave and resourceful Enola save "nice-but dim" Tewkesbury from various antagonists who try to prevent his vote being cast. What's at stake here is the fight between those, like Mycroft and Tewkesbury's enemies, who will go to any ends to preserve the existing order and those, like Enola, who believe that "the world needs changing".

In a powerful scene, Susan Wokoma, who runs a radical teashop and women's jujitsu group, chides Sherlock that his indifference to the Tewkesbury case and political matters is not evidence of his high-mindedness, but instead speaks of his privilege: "You have no interest in changing a world that suits you so well… You don't know what it is to be out of power." He is lacking the political awareness that his radical sister embodies because existing structures of power benefit men just like him.

This scene illuminates the whole existential question around which the film is built: can the actions of a passionate young woman change the world? Contrary to what the Doyle estate would have us believe, Sherlock's emotions, or lack of, are inconsequential.

What matters is the emotional ferocity of Enola, not Sherlock, Holmes. It is pertinent that a story so concerned with these questions of political power appears weeks before the most important American election of our lifetime. The headlines of the Pall Mall Gazette read by Sherlock trumpet 'Every Vote Counts' - a reference to the importance of Tewkesbury's role in enacting change.

This message, combined with the suffragette sub-plot, reminds us that the right to vote was hard won and should not be squandered. "To be a Holmes you must find your own path," Enola tells.

Sherlock, always in the background in this movie, has already found his path as a genius investigator. Here, Enola finds her path and, in doing so, helps to dismantle unequal power structures.

To the viewer, Enola Holmes extends an invitation not to leave it up to successful middle-aged men like Sherlock to change the world. Her final words are a rallying call to passionate young people like herself: "The future is up to us."

'Enola Holmes' will be released on Netflix from Wednesday

Clare Clarke is Lecturer in 19th-Century Literature at Trinity College Dublin. Her 'British Detective Fiction 1891-1901: The Successors to Sherlock Holmes' was published in July

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news