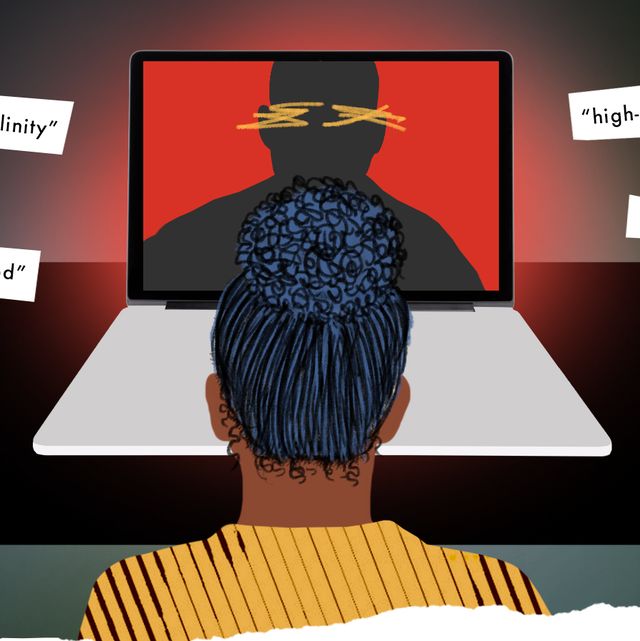

“I believe women are hypergamous. It’s an observable fact,” my date declared matter-of-factly as we stared at each other across the abyss of Zoom. About an hour earlier, when the evening started going downhill, I began writing down the words I didn’t understand but knew I’d heard before. So, I added “hypergamous” to the list. His previous mentions of “pair bonded,” “high-value men,” and “dominant masculinity” all sounded ominously familiar as well.

In the end, my date (let’s call him King) and I talked for nearly three hours. King explained that I was behaving in a masculine way when I invited him to meet me for a date (instead of waiting for him to ask me), claimed it was a biological fact that in any romantic relationship someone (who’s cisgender and male, of course) needed to dominate the other, and feminism was a force that had only served to divide the Black community and alienate Black men. That last part came after I “revealed” that I am a feminist, something he told me was usually a complete non-starter for him.

It was like the trolls I saw skulking around the edges of Black Twitter had jumped up from under their technicolor bridges and wandered directly into my dating life. The sirens clanging in my head throughout this entire ordeal bleated out one word over and over again: incel. For months, I had seen similar words and themes being used on social media. On Twitter, men that wield a particular animus against Black women are sometimes derogatively called “nigcels.” I had to find out how the language of “chads” and “hypergamy,”—both terms I associated with white men on the internet, the latter a claim that women only date men of higher social status—had mapped onto the world of Black men.

According to Aaron Fountain Jr., a Ph.D. candidate at Indiana University, it’s less about incels in the case of Black men than the Manosphere, a more racially diverse space on the internet that includes men of all ages and has developed its own offshoot, the Black Manosphere. Within the Black Manosphere’s fiefdom, there are many subgroups, rival influencers, competing philosophies, and myriad content creators. But each of them contain one common thread: a concerted, explicit disdain for Black women.

In all parts of the Manosphere, men talk about taking the “red pill,” a Matrix reference that indicates that they have woken up to the purported “truth” about women. In some corners of the Black Manosphere, men grumble about the very popular YouTuber Kevin Samuels and his ilk, because Samuels allows the Black women he berates on his show to speak at all. In his lane, influencer Mr. Palmer has coined the term “Baby Mama Terrorists,” or BMT, and he and his followers sport Fuck Child Support hats. Dr. Shawn “Thunder” Wallace, a tenured professor at The Ohio State University, is an influencer whose work teeters at the edge of the Manosphere, beckoning in Black men who might want to explore further.

The content creator Mad BusDriverX1 (MBD for short), who films his YouTube videos wearing a helmet, would only consent to being interviewed over email. He’s a founder of the Save Yourself Black Men, or SYSBM, community, but insists the group is not a part of the Black Manosphere, claiming that space has “different goals and objections” than SYSBM. In his videos, he spends hours describing the ills of Black women, the deterioration of the Black race, the importance of travel for Black men, and the virtues of dating and marrying anyone but American Black women.

In one video, titled “protect your seed black men invest it into white Asian or Latina,” MBD’s language veers close to eugenics as he addresses the Black men listening, saying, “There’s going to be two types of Black people in the future and one’s going to be Black-ish and one’s going to be traditionally Black...the permanent underclass, you know what that’s going to be. No disrespect, if you’re a Black man who needs to save himself go on ahead...because you can’t save it, it’s ingrained, you’ve got to let it [the Black race] die out because they don’t want to change.” When asked if this use of eugenics language was intentional or if he was at all concerned about the historic weaponization of eugenics language against Black men and women, MBD responded that SYSBM is about freedom for Black men, rooted in their ability to choose better for themselves.

While SYSBM’s philosophy is deeply alarming, its foundation—the perception of Black people as pathologically violent, lazy, and unintelligent—is hardly new. The language of Black respectability and the “betterment” of the Black race has existed for generations; its most prominent proponents range from the scholar W.E.B. DuBois to pop culture figures like Bill Cosby. The Black Manosphere is fueled by this presumed cultural deficiency and shades of Black respectability politics. According to Fountain, the 1965 “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action” is a regularly quoted text in the Black Manosphere. Often referred to as the Moynihan Report and commissioned by then President Johnson, this report has for decades created a pseudo-anthropological argument claiming that Black people and their culture were at fault for their own second-class citizenship in America.

If you’re wondering how a 60-year-old, oft-debunked government report holds so much weight among some Black men, whom it also seems to disparage, the answer seems to be, in part, its enduring place in white conservative talking points about Black families and communities. But even more critically for the Black Manosphere, the Moynihan Report places the responsibility for a stated Black pathology squarely on the shoulders of Black women. It was the Moynihan Report that propelled generations of ire toward Black woman-led households and served as the basis for the Reagan-era Black “welfare queen” stereotype. Its author, then-Assistant Labor Secretary Daniel Patrick Moynihan, admonished, “Given the strains of the disorganized and matrifocal family life in which so many Negro youth come of age, the Armed Forces are a dramatic and desperately needed change: a world away from women, a world run by strong men of unquestioned authority...”

On our Zoom date, King had also bemoaned the idea of Black women leading anything from households to topics of conversation. His belief, one clearly indebted to the legacy of Moynihan’s report, was that Black men’s supremacy in heterosexual relationships is the healing balm the Black community needs to subvert a racial caste system.

Mumia Obsidian Ali, a Philly resident and self-described “co-founder” of the Black Manosphere, told me has a great deal of respect for Moynihan and his report. Over the past 12 years, Ali says his writing and videos have been featured on “just about every Black Manosphere venue” of note. According to Ali, he sought to establish and expand the Black Manosphere because “Black women as a group have long enjoyed a megaphone to air out their grievances, much of it—not all of it—concerning Black men...And I got tired of being left out of the conversation.”

Ali initially refused to be interviewed until I read his 42-chapter screed on Black dating. When we finally spoke via Zoom, our conversation began at an imbalance. Ali started not with a greeting, but instead by playing a fake advertisement for the “Wookie Weave Warehouse,” presumably a dig at my own purple box braids. (He kept his own camera off.) In his book, Ali defines Wookie Weave as “hair extensions, lace front wigs, hair weaves and other hair appliances Black women are known to use in their daily beauty regimen. Many Black men do not like them on Black women, particularly when it comes to long term mating.” The ad not only featured the braying of Star Wars’ Chewbacca, it offered to throw in Elmer’s glue to keep the weave on my head. Overall, the targeting felt consistent with Ali’s written and public profile. Throughout his dating guide for “non-select” Black men, for instance, Ali decries the marginalization of Black men at the hands of Black women, whom he crowns with such titles as Paper Tigress, Spinster, Mizz Thang, and Victim Queen, to name a few.

Like the white Manosphere, the Black Manosphere is right-wing and politically conservative. (Ali proudly said he voted for Trump twice.) Its content creators perpetuate the belief that Black women—not systemic economic, political, or social oppression—are to blame for any inequities Black people, especially Black men, observe in their lives.

Packaging and repackaging this message is how the Manosphere grows its audience. Jamaal Muwwakkil, a Ph.D. candidate and linguist at University of California, Santa Barbara, has been researching conservative political groups as well as the linguistic and cultural memes that conservatives use to recruit young people. Muwwakkil explained how using memes in spaces like the Black Manosphere serve both as tools for community building and self-identification.

“I like to look at [these memes] as cultural signifiers, where I can signal to you who I am, where I'm from, what I know, quickly. By quoting a song lyric or a movie quote or referencing even with my body. It doesn’t even have to be verbal,” Muwwakkil says. “It kind of provides for a plausible deniability, which was the other function of memeing. You get to [joke] your way out of any sticky situations. But if a person believes [your meme], I can see, ‘Ah, you, too, are a man of culture.’”

In addition to “red pill” language, the Black Manosphere is awash in these memes. Ali, Samuels, Dr. Thunder, and many others use sound clips to reinforce negative portrayals of Black women (i.e. their tendencies toward “Wookie Weave” or the “idiot woman” sound loop Kevin Samuels directs at his callers). As Muwwakkil observes, the ever-expanding lexicon of Black Manosphere memes allows for its most harmful themes about Black women to be disguised in everyday conversations as off-color humor. In fact, when I asked Fountain about how he discovered the Black Manosphere, he admitted that, initially, he’d seen its videos as entertaining, absurdist humor.

Toxic archetypes of Black womanhood—the mammy, the Black matriarch, the jezebel (or the Scraggle Daggle, in SYSBM parlance), and the welfare mother—are all alive and well in the Black Manosphere. The research of Dr. Patricia Hill-Collins, a preeminent Black feminist scholar and distinguished professor emerita at the University of Maryland, shows that such images have been used since Black people’s forced arrival in the country to justify Black women’s dehumanization by racist systems and to mask the physical and psychological harm they experience. The Black Manosphere breathes new life into these long-standing cultural memes and helps to reanimate their virulence in digital spaces.

A 2018 study analyzing the abusive and violent tweets women receive on Twitter found that Black women are 84 percent more likely than their white counterparts to experience violent threats and language on the platform. The vast majority of that language was racialized. Dr. Sarah Adeyinka-Skold, an assistant professor of sociology at Furman University, has seen these truths born out in her research on the dating lives of heterosexual Black women. She explains that on dating apps, Black women are often not selected by male partners, and when they do garner attention, tropes of them as sluts or welfare queens also mean they face fetishization and derogatory language. According to Adeyinka-Skold, “[Black women] are the only racial group to be excluded by non-Black men and Black men.”

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the Black Manosphere is the immense amount of pain its content creators appear to be in, even as they dispense supposedly clear-eyed truths. Their own rejection and ostracization has been transmuted into a blunt object used to bludgeon their way to supposed relevance. When I asked Ali what a realistic (by his standards) Black romance movie would look like, he replied, “80 percent of the guys get looked over while 20 percent of the guys get the ladies, who then screw the ladies over. And the Black ladies complain that Black men ain’t shit.” And yet, the loss these Black Manosphere content creators feel at not holding a “select” or “high-value” position in society is never channeled into anger at systems like racism, colorism, classism, or fatphobia. Instead, their crosshairs are steadfastly trained on Black women and feminism.

During our interview, Ali asked me why I am a feminist. I had answered a similar question from my date, months before, in almost the exact same way. I told them both that, for me, Black queer feminism provides a lens and a framework through which to see myself and other people (of all genders) more expansively. I explained that Black queer feminist scholars have pushed me to question the limiting nature of white dominant definitions of masculinity and femininity. I talked about the freedom to see each other, especially Black people, as whole, myriad, and not boxed in by what we are told we have to be. Strangely, or perhaps miraculously, they both agreed with this part of the feminist doctrine they purport to hate. “Being more expansive,” Ali mused. “I have no problem with that.”

Nicole Young is a writer whose work has appeared in ZORA and Bitch magazine. She loves to talk about race, Black womanhood, politics, and children’s literature. She currently lives in Philadelphia.