Instrument of Repression

Since 2011, Saudi Arabia’s Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) has been used as an instrument of repression to silence dissent. The impact has been chilling. Among those the court has punished severely are journalists, human rights defenders, political activists, writers, religious clerics and women’s rights activists. Resorting extensively to the country’s draconian counter-terror law and Anti-Cyber Crime Law, the SCC’s judges have presided over grossly unfair trials and handed down prison sentences of up to 30 years and numerous death sentences.

In its new report “Muzzling Critical Voices: Politicized Trials Before Saudi Arabia’s Specialized Criminal Court”, Amnesty International has documented the cases of 95 individuals, the vast majority men, who were tried before the SCC between 2011 and 2019. They include many individuals tried on charges arising solely from the peaceful exercise of their rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly. It has recorded the grim details of their cases and the patterns of human rights violations they expose.

Several Saudi Arabian Shi’a Muslims, including young men tried for “crimes” committed when they were under the age of 18, were at imminent risk of execution following grossly unfair trials before the SCC. They have good reason to fear the worst – at least 28 Saudi Arabian Shi’a Muslims have been executed since 2016.

Join our campaign to release all prisoners of conscience in Saudi Arabia and ensure that desperately needed reforms are introduced to end the travesty of justice embedded in the SCC.

The presumption of innocence is not part of the Saudi Arabian judicial system.

Taha al-Hajji, lawyer who has represented many defendants before the Specialized Criminal Court

Tell the King of Saudi Arabia, King Salman, to immediately and unconditionally:

FREE ALL JAILED ACTIVISTS

WATCH SALEM’S STORY

Human Rights Reform: Rhetoric vs. Reality

The Saudi government’s rhetoric about reforms, which increased after the appointment in June 2017 of Mohammad bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud as Crown Prince, stands in stark contrast to the reality of the human rights situation. Alongside some positive reforms, particularly with regards to women’s rights, the authorities have unleashed an intense crackdown on citizens promoting change, including economists, teachers, clerics, writers and activists – peaceful advocates of the very reforms the Crown Prince was promising or enacting. Strikingly, since 2017 the Saudi authorities have targeted virtually all human rights defenders and other government critics through arbitrary arrests, torture and prosecutions before the SCC and other courts.

Strikingly, since 2017 the Saudi authorities have targeted virtually all human rights defenders

Amnesty International

Indeed, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud and the Crown Prince have tightened their grip on the country’s investigative, prosecutorial and security agencies. In October 2017, the Law on Counter Terrorism and its Financing replaced the 2014 counter-terror law. This consolidated state security-related powers in the hands of the King by delegating the authority to arrest, investigate, interrogate and refer individuals to the SCC to the newly established Public Prosecution and Presidency of the State Security, both of which report directly to the King. The new law also introduced the death penalty for “terrorist crimes”, as well as provisions that punish severely acts that may amount to nothing more than people peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly.

Read the Full Report

Muzzling peaceful expression and association

Today, virtually all Saudi Arabian human rights defenders and independent voices, male and female, are behind bars serving lengthy sentences handed down by the SCC. Most were prosecuted for their peaceful human rights work and calls for reforms. Among them are all the founding members and many supporters of four independent human rights groups that the authorities closed down in 2013 who had remained in the country. Many dissidents, activists and independent thinkers have fled the country to avoid such persecution.

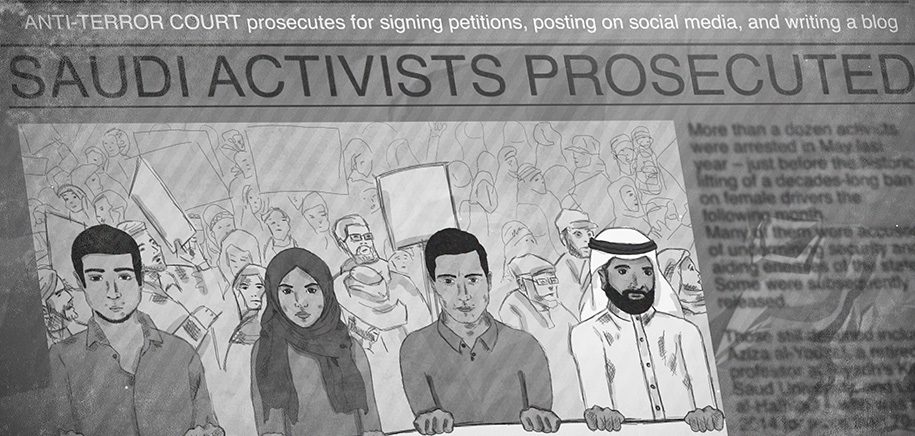

Many of those condemned by the SCC have been punished for expressing dissent, advocating change, criticizing the authorities, exposing abuses by the General Directorate of Investigations (GDI) or highlighting the failures of the judiciary, often through the use of social media. Since 2011, Amnesty International has documented the trials and sentencing of 27 such individuals by the SCC. It considers 22 of the 27 still detained to be prisoners of conscience and calls for their immediate and unconditional release.

Since September 2017 and in several waves of arrests that followed in May 2018 and April 2019, the authorities have arbitrarily arrested scores of individuals, including prominent women’s rights activists, writers, clerics and family members of activists. While many of those detained remain in detention without charge or trial, others are facing trial before the SCC and other courts following a terrible ordeal of prolonged pre-trial detention and torture and ill-treatment prior to the beginning of their trial.

For example,Mohammed al-Bajadi, who was previously prosecuted for his human rights work, was rearrested in May 2018 and remains in detention with other activists without charge or trial. Salman al-Awda, a reformist religious cleric arrested in September 2017, faces the death penalty in his trial before the SCC.

Women human rights defenders, includingLoujain al-Hathloul, Iman al-Nafjan, Aziza al-Yousef, Samar Badawi and Nassim al-Sada, were expected to appear before the SCC but were instead brought before the Criminal Court in Riyadh to be tried for their peaceful human rights work and campaigning for women’s rights.

From combating terror to stifling dissent

The SCC was established in October 2008 to try individuals accused of terror-related crimes. Initially, it tried suspected members and supporters of the armed group al-Qa’ida. However, the referral of a group of 16 “Jeddah reformists” to the SCC in May 2011 marked a decisive shift in the court’s work to include cases involving individuals who the authorities simply wanted to silence. Soon after, the SCC tried and sentenced a founding member of the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association (ACPRA). Since then, many others have faced grossly unfair trials before the court for peaceful exercise of their fundamental rights.

The SCC does not operate according to clearly established and defined procedures. The Supreme Judicial Council appoints the judges, without any transparent criteria for the appointments. Human rights lawyers and activists believe that the main criterion is a judge’s perceived loyalty to the government rather than legal knowledge, expertise or integrity.

The authorities prosecute individuals before the SCC on vague or overly broad charges that are not clearly defined in law and which, in some cases, equate peaceful political activities with terrorism-related crimes. In the list of charges used in proceedings before the SCC made available to Amnesty International, the most common were:

Some of the charges are themselves contrary to human rights law and standards because they criminalize the peaceful exercise of human rights. The 2014 counter-terror law gave the SCC exclusive jurisdiction to try those accused under the law and to apply the law retrospectively. Some individuals already convicted by other courts found themselves before the SCC facing similar charges but harsher sentences under the counter-terror law.

The 2017 version of the law, like its predecessor, contains overly broad and vague definitions of “terrorism”, “terrorist crime” and “terrorist entity”. It also introduced provisions that punish peaceful expression of views. For example, it imposes up to 10 years’ imprisonment for directly or indirectly insulting the King or Crown Prince in a way that impugns religion or justice. The authorities have also resorted extensively to the 2007 Anti-Cyber Crime Law when prosecuting government critics and human rights defenders before the SCC, citing tweets and other online messages as evidence.

Share this page

Today, virtually all Saudi Arabian human rights defenders and independent voices, male and female, are behind bars serving lengthy sentences handed down by the SCC.

Amnesty International

CRUSHING SHI’A PROTESTS IN EASTERN PROVINCE

Since 2011, the authorities have sustained a vicious crackdown on the country’s Shi’a Muslim minority to defeat protests demanding greater rights and reforms as well as the release of detainees held without charge. Hundreds have been arrested in connection with protests in al-Qatif governorate in the Eastern Province, which is predominantly populated by Shi’a Muslims. Most of those arrested were subsequently released without charge. The rest were detained without charge or trial for a year or more, and then charged and brought to trial before the SCC.

As tensions mounted in the Eastern Province, two Shi’a clerics known for their critical stance towards the government – Nimr al-Nimr and Tawfiq al-Amr – delivered sermons on 25 February 2011 supporting calls for urgent political and religious reforms. Both were arrested. Arrests continued as the protests persisted and on 5 March 2011, the Ministry of Interior confirmed a long-standing ban on protests deemed to “contradict Islamic Shari’a law and the values and traditions of Saudi society”.

Since then, over 100 Saudi Arabian Shi’a Muslims have been brought before the SCC in relation to both peaceful criticism of the government in speeches or on social media and participation in anti-government protests. They have been tried on vague and varied charges ranging from organization or support for protests to alleged involvement in violent attacks and espionage for Iran.

In addition, Shi’a Muslims have been condemned to death and executed for crimes committed when they were below 18 years of age, after they were found guilty by the SCC on the basis of torture-tainted “confessions”. Three young men – Ali al-Nimr, Abdullah al-Zaher and Dawood al-Marhoon ¬– who were arrested separately in 2012 aged 17, 16 and 17 respectively, are at imminent risk of execution after they were sentenced to death after grossly unfair trials before the SCC.

On 2 January 2016, the authorities announced that Nimr al-Nimr and 46 other death row prisoners had been executed, sparking renewed protests in Eastern Province. Adding to the tension, the SCC continued to hand down death sentences and long prison terms to Shi’a Muslims convicted of protest-related crimes. In July 2017, a number of Shi’a men sentenced to death by the SCC were executed, and in April 2019 a mass execution of 37 men, the majority of them Shi’a, was carried out.

The first time I saw Yusuf I did not recognize him. When he started talking about his torture during our first visit I needed to see for myself, so I asked him to show me what was under his robe. I was shocked.

Person close to Yusuf al-Mushaikhass, who was executed on 11 July 2017 for offences related to participation in protests in the Eastern Province

Gross Violations of the Right to a Fair Trial

Trials before the SCC are a mockery of justice. The hearings are frequently held wholly or mostly in secret. The judges demonstrate clear bias against defendants. They do not rigorously examine and question prosecutors’ assertions, and routinely accept defendants’ pre-trial “confessions” as evidence of guilt without investigating how they were obtained, even when the defendants retract them in court and say they were extracted by torture.

The SCC has tried and convicted defendants in the absence of defence lawyers, in some cases after barring them. Judges have also used their powers to convict defendants on vague charges that do not constitute recognizable crimes, and treat peaceful dissent, the protection of human rights and advocacy of political reform as crimes against the state or acts of terrorism.

Amnesty International closely reviewed eight SCC trials of 68 Shi’a defendants, the majority of whom were prosecuted for their participation in anti-government protests and of 27 individuals prosecuted for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and association. In all cases, it concluded that the trials were grossly unfair, with defendants convicted on vague, “catch-all” charges that criminalize peaceful opposition as “terrorism” and in many cases sentenced to death on the basis of torture-tainted “confessions”.

In fact, the whole process of justice linked to the SCC is deeply flawed from the moment of arrest to final appeal. Most defendants in the trials documented by Amnesty International were:

- arrested without a warrant;

- not told the reasons for their arrest;

- held incommunicado, often in solitary confinement, without access to their families or a lawyer, for days, weeks or months;

- tortured or otherwise ill-treated in pre-trial detention to extract “confessions”, as punishment for refusing to “repent”, or to force detainees to pledge to stop criticizing the government;

- held without charge or trial, without any opportunity to challenge their detention, for up to three and a half years.

One of the most striking failings of the SCC in the trials reviewed by Amnesty International is its unquestioning reliance on torture-tainted “confessions”. At least 20 Shi’a men tried by the SCC have been sentenced to death on the basis of such “confessions”, 17 of whom were executed.

Hussein al-Rabi’, a defendant in a mass trial of protesters from Eastern Province, told the SCC that his interrogator had slapped and hit him, and threatened to hang him by his arms and give him electric shocks unless he “confessed”. He also told the SCC that his interrogator had threatened to torture him if he refused to confirm his “confession” before a judge. Indeed, when he did refuse to confirm it, he was denied food and water, causing him to lose consciousness and be taken to hospital. He was already suffering from eight bullet wounds sustained during arrest. Hussein al-Rabi’ was executed in April 2019.

Every single defendant in the SCC trials reviewed by Amnesty International was denied access to a lawyer from arrest and throughout their interrogation in GDI prisons. The best they experienced was to meet their lawyer at the opening session of their trial. During the trials, defendants were denied the opportunity to prepare and present their case, or to contest arguments and evidence put against them on an equal footing with the prosecution.

Finally, the right to appeal is violated. Appeals against SCC judgements are conducted behind closed doors without the presence or participation of defendants or their lawyers. In many cases, defendants are not informed in advance of the SCC Appeal Court hearing and only find out after the fact that their appeal had been rejected. Often, the judicial authorities do not inform defendants, their lawyers or their families of the outcome of appeals, even when death sentences have been upheld.

Amnesty’s Recommendations

Amnesty International has made recommendations to various authorities to ensure that desperately needed reforms are introduced to end the travesty of justice embedded in the SCC. Among other things, Amnesty International calls on:

- The King and Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia to release all prisoners of conscience immediately and unconditionally, ensure their convictions and sentences are quashed, and declare an official moratorium on all executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty.

- The Supreme Judicial Council to fundamentally reform the SCC to ensure it is capable of conducting fair trials, is protecting defendants from arbitrary detention, torture and other ill-treatment, and overseeing fair hearings deciding on appropriate reparation to all victims of torture and other human rights violations by state officials or those acting on their behalf.

- The Public Prosecution to ensure that all those against whom there is sufficient admissible evidence of responsibility for torture or other ill-treatment are promptly prosecuted on criminal charges in fair trials and, if convicted, given sentences commensurate with the gravity of the offence without recourse to the death penalty.

- The Council of Ministers to establish an independent commission of inquiry into the use of torture and other ill-treatment by the GDI and other state agents; to repeal or amend the counter-terror law and the Anti-Cyber Crime Law to make them compatible with international human rights law and standards; and to ensure the death penalty is not imposed on anyone under the age of 18 at the time of their alleged

- Saudi Arabia’s strategic allies to urge the Saudi Arabian government to fully respect and observe international human rights law and standards.

- The UN Human Rights Council to set up a monitoring mechanism of the human rights situation in Saudi Arabia.