Hong Kong protesters made history in 2019

In March 2019 the government of Hong Kong proposed a bill that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China. In response, the people of Hong Kong took to the streets in record-breaking numbers.

On one day, 16 June, up to 2 million people marched peacefully in the streets of Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong police have responded to the protests with batons, tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets and water cannons.

Although the Extradition Bill has now been dropped, the movement has evolved into a much wider call for change and protests in Hong Kong continue.

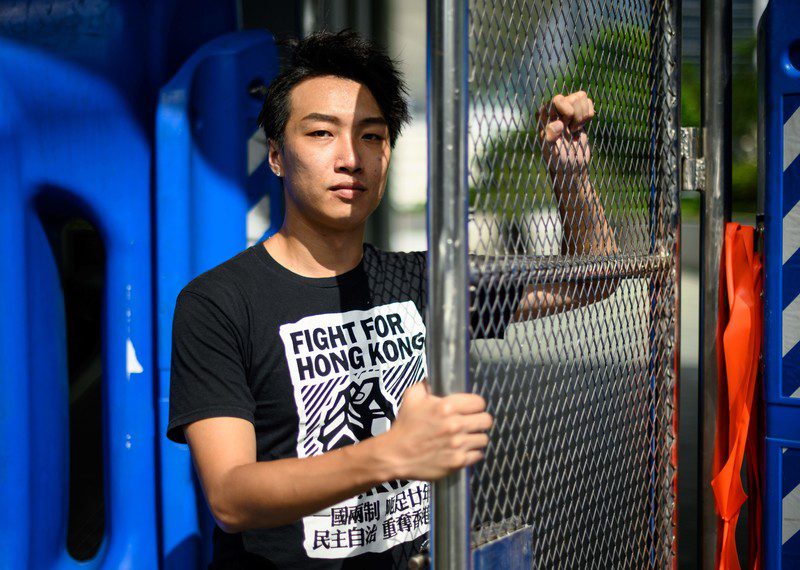

This movement has shown how many Hong Kongers want fundamental changes

Suki, student and activist

“Five demands, not one less”

The withdrawal of the Extradition Bill was only one of the “five demands” that have propelled the movement.

Protesters also want the government to retract its characterization of protests as “riots”; an independent investigation into use of force by police; and the unconditional release of everyone arrested in the context of protests.

They also want political reform to ensure genuine universal suffrage – the ability to choose Hong Kong’s leaders themselves – as set under the city’s mini-Constitution, the Basic Law.

Amnesty International welcomes the bill’s withdrawal and is calling for an independent, impartial investigation into use of force by the Hong Kong police.

One student’s experience

Joey Siu is a student at Hong Kong City University. She told Amnesty International:

“The first time I experienced tear gas was on 12 June. It was a very, very bad day. I was trying to distribute protective gear to protesters when tear gas was suddenly deployed at our first aid station.

“Tears poured uncontrollably from my eyes and I could hardly breathe. Other people have been beaten up by the police just for taking part in protests.

“This is why there needs to be an independent investigation into police actions, and one of the reasons why we aren’t backing down.”

The root causes of protests

One country, two systems

Hong Kong was a British colony until 1997, when sovereignty of the territory was returned to China. Under the deal struck between the UK and China, Hong Kong was guaranteed a separate legal and economic system.

The deal also guaranteed the continued protection of a range of human rights in Hong Kong. The principle of “one country, two systems” was enshrined in Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

China’s “red line”

The autonomy and freedoms that Hong Kong is supposed to enjoy have come under attack in recent years. In2017, President Xi Jinping warned that any attempt in Hong Kong to endanger China’s “national sovereignty and security” or to challenge the power of the Central Government crossed a “red line” and should be dealt with harshly.

Chinese authorities have a very broad interpretation of what constitutes a threat to sovereignty and national security. Peaceful criticism, journalism and activism are regularly punished harshly in mainland China.

Beijing considers pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong to be a threat to China’s national security. The Hong Kong authorities have increasingly been using this justification to target activists, especially since the 2014 “Umbrella Movement”.

“Hong Kong is not far from being a part of the closed system of China, completely without freedom and democracy”

Lam Wing-hang, former student union leader

Report: Beijing’s “Red Line” in Hong Kong

How not to police a protest

Tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Hong Kong on Wednesday, 12 June.

From late afternoon into the night on 12 June, the largely peaceful protesters faced an onslaught of tear gas, guns firing rubber bullets, pepper spray and baton charges from police to disperse the demonstration near government headquarters. These unlawful police actions posed a serious risk of severe injury, or even death, to protesters.

Amnesty International’s team of experts on policing and digital verification took a closer look at this unnecessary and excessive use of force by police. We examined in detail footage from 14 instances of apparent police violence, including brutal beatings and the misuse of tear gas and pepper spray.

Since then, Hong Kong police have deployed excessive force numerous times.

On 12 August a protester suffered a ruptured eye in Tsim Sha Tsui after being shot by what appeared to be a bean bag projectile.

Reckless and aggressive policing

More than 1,300 people have been arrested so far in the context of the Extradition Bill protests, and the number continues to rise. Amnesty International interviewed 21 people, almost all of whom described being beaten with batons and fists during their arrests, even when they posed no resistance. Anti-riot police and a Special Tactical Squad (STS), commonly known as “raptors”, have been responsible for the worst violence.

One man who was arrested at a protest in Tsim Sha Tsui in August described how he ran away from police as they charged at protesters. When STS police caught up to him:

“Three of them got on me and pressed my face hard to the ground. A second later, they kicked my face …they kept putting pressure on my body. I started to have difficulty breathing, and I felt severe pain in my left ribcage … They said to me, ‘Just shut up, stop making noise. You came out; you’re a hero, right?’”

The man spent two days in hospital and was diagnosed with a fractured rib, among other injuries. Other arrested protesters described injuries including bone fractures, a cracked tooth and bleeding from head wounds.

I started to have difficulty breathing, and I felt severe pain in my left ribcage

Policing standards

The vast majority of Hong Kong protesters remain peaceful. However, there has been violence, which appears to be escalating alongside excessive use of force by the police. Police have also failed to act when protesters and journalists have been attacked by others.

While police have a duty to maintain public order, there are strict international human rights laws and standards governing the use of force.

If law enforcement decides to use force, it must be in strict compliance with the principles of legality, necessity and proportionality.

I am optimistic about the future for Hong Kong. The government may chip away at our freedoms, but change will come. There will be darker times ahead for Hong Kong but the sun will rise again. We need to keep strong.

Benny Tai, professor and pro democracy activist