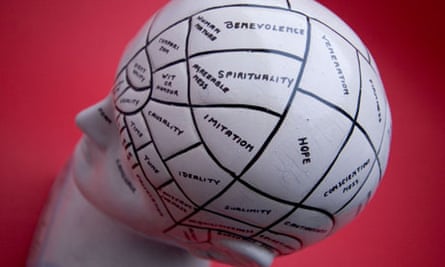

"Why don't they kill us?" asks Calvin Candie, the southern slave owner in Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained. He wants to know why the African slaves he brutalises do not rise up and take revenge. Before long, he has the skull of a recently deceased slave on the dinner table. "The science of phrenology," he announces, "is crucial to understanding the separation of our two species." He hacks away at the back of the skull with a saw, removing a section of the cranium and pointing to an allegedly enlarged area. In African slaves, Candie claims, this bump is found in the region of the brain associated with "submissiveness".

For Candie, phrenology not only explained slavery, it justified it.

Needless to say, phrenology has now been thoroughly debunked: the idea that the shape of the skull can be used to infer mental characteristics is just plain wrong. But it was extremely popular all over the world during the 19th century, finding converts among reform-minded Bengalis in Kolkata, India, and colonial settlers in Australia. As part of my research into the global history of phrenology, I came across the real-life Calvin Candie.

He was called Charles Caldwell, a doctor from Kentucky who revelled in both phrenology and slave ownership. As in the film, Caldwell was a Europhile, travelling to Paris in the 1820s where he picked up the latest medical craze. He later returned to France in the 1840s in order to hobnob with Pierre Marie Dumoutier, a phrenologist just back from a three-year round-the-world voyage.

At the time, Dumoutier's immense collection of skulls and casts could be found at the Musée de Phrénologie in Paris. There Caldwell could practise phrenology, feeling for bumps on the heads of Tahitians and Marquesas Islanders. No doubt he was considered very à la mode back in Kentucky. In fact, Caldwell even boasted of being one of the earliest experts in phrenology in the United States.

Caldwell deployed phrenology in almost exactly the same manner as the fictional Candie. In 1837 he wrote to a friend claiming that "tameableness" explained the apparent ease with which Africans could be enslaved. This was a standard phrenological argument. Areas located towards the top and back of the skull, such as "Veneration" and "Cautiousness", were routinely claimed to be large in Africans. His correspondent concurred, writing: "They are slaves because they are tameable." Clearly enjoying himself, Caldwell replied: "Depend upon it my good friend, the Africans must have a master."

It's worth emphasising that these words are not from a Tarantino script, crafted for Hollywood shock value. They were written by a slave owner desperate to preserve his brutal way of life. And, while the physical violence of slavery is masked in Caldwell's letters, they betray his warped sense of morality. In a letter written on Christmas Eve 1838, Caldwell made the outrageous claim: "My slaves live much more comfortably than I do."

The fact that phrenology was used to justify slavery is perhaps unsurprising. What would one expect from such an overtly racist science? But it wasn't just the slavers. My research revealed that some of the most vocal anti-slavery campaigners of the 19th century were also advocates of phrenology, and used it to justify their stance.

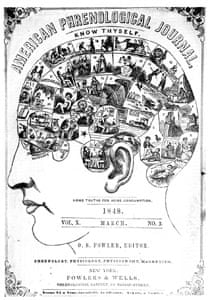

Lucretia Mott, a particularly uncompromising American abolitionist, sent her children to phrenological lectures and spoke of the "truth of phrenology" in letters to friends. When she visited Britain she stayed with the renowned Scottish phrenologist George Combe, himself an anti-slavery campaigner. Horace Mann, another major figure in abolitionist politics, was so keen on phrenology that he subscribed to the official journal. After becoming president of Antioch College in Ohio, he even boasted in the same sentence that the professors he employed were both "anti-slavery men" and "avowed phrenologists".

These are not isolated examples. If anything, the majority of phrenologists were against slavery.

How can this be? George Combe, a man whose phrenological books sold more copies during the 19th century than Charles Darwin's Origin of Species, explained his reasoning: "The qualities which make them submit to slavery are a guarantee that, if emancipated and justly dealt with, they would not shed blood."

For abolitionists, the apparent weakness and timidity of the Africans served two purposes. It countered fears that they would take revenge on their masters if set free. It also provided a moral argument: if Africans were innately weak, society should help them, not enslave them.

In the 19th century, scientific racism and abolition were by no means mutually exclusive.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion