New students are streaming into law schools across the country. But to become the next generation of lawyers, judges and activists, they’ll first need to read through a mountain of case law. In case law, judges define what acts of parliament actually mean, explain the common law and resolve disputes between citizens, organisations and sometimes state institutions.

Newspapers occasionally publish a list of the most important cases for students to be aware of. But it’s not just students who could benefit from learning about the law – after all, cases decided hundreds of years ago can set the precedent for decisions that the courts in England and Wales make today.

Here’s my pick of some of the most important cases throughout history: ones that can teach us all something about how the law mirrors social and political attitudes, while revealing the principles and patterns that make up the country’s version of justice.

1. The Case of Proclamations, 1610

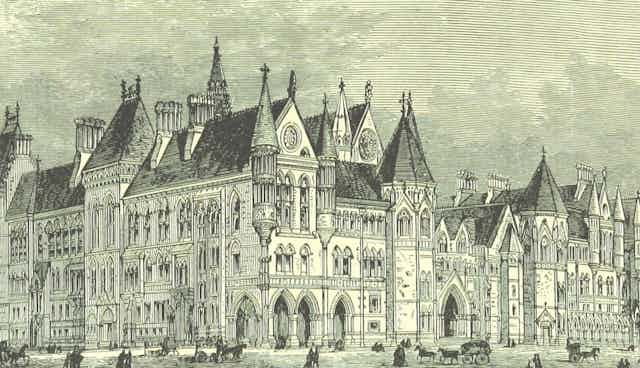

Over 400 years ago, the chief justice, Sir Edward Coke, ruled that King James I could not prohibit new building in London without the support of parliament. King James believed that he had a divine right to make any laws that he wished. But the court opposed his view, and decided that the monarchy could not wield its power in this arbitrary way.

By the end of that century, the Glorious Revolution laid the foundation for today’s constitutional monarchy, whereby whoever is king or queen respects the law-making authority of the elected parliament.

2. Entick v Carrington, 1765

Author and schoolmaster John Entick was suspected of writing a libellous pamphlet against the government. In response, the secretary of state sent Nathan Carrington, along with a group of other king’s men, to search Entick’s house for evidence. Entick then sued the men for trespass.

The court decided that the secretary of state did not have the legal authority to issue a search warrant, and therefore Carrington had trespassed. This case reflects the principle that “no man is above the law” – not even the secretary of state. To this day, law enforcement agencies may only do what the law allows.

3. R v Dudley and Stephens, 1884

In this case, the survivors of a shipwreck who killed and ate the youngest and weakest crew member were prosecuted for murder. Their defence was based on “necessity” – that they needed to eat the boy, as they were unlikely to survive and the boy probably would have died anyway.

It may have been a “custom of the sea” that cannibalism was allowed under such circumstances, but the defendants were found guilty on the basis that all life is equal – the law expected them to die, rather than kill another.

But the public was sympathetic to the defendants, and their sentences were later commuted from death to six months imprisonment. The boy was named Richard Parker, as is the tiger in the Man Booker prize-winning novel Life of Pi.

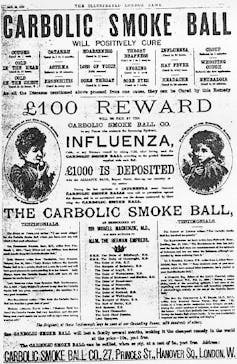

4. Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co, 1893

Mrs Carlill sued the manufacturer of the carbolic smoke ball – a device for preventing colds and flu – which had promised a reward of £100 for any one catching flu following the use of its product but then refused to pay out.

The court decided that this promise, together with Mrs Carlill’s use of the product as directed, amounted to a legally binding contract and she was entitled to the reward. The case explores many of the principles that must be present in modern day contracts, such as offer and acceptance, before we can make legally enforceable agreements between each other. Yet this most famous of cases may never have been brought at all, had Mrs Carlill not been married to a solicitor.

5. Donoghue and Stevenson, 1932

In a case originating in Scotland, Mrs Donoghue was given a bottle of ginger beer which allegedly contained the decomposed remains of a snail. She claimed to have suffered shock and gastroenteritis as a result. But as she had not bought the drink herself, she had no contract on which to sue.

Nevertheless, the court extended the law of negligence to require reasonable care towards those likely to be affected by a person’s or company’s actions. Was there really a snail? We don’t know for sure, as Mr Stevenson died before the evidence could be heard.

6. Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner, 1969

To be guilty of a criminal offence, there often needs to be unlawful act accompanied by a guilty state of mind, such as a criminal intent. So, having accidentally driven his car onto a policeman’s foot, did Mr Fagan commit an assault when he decided not to remove it?

Mr Fagan suggested not because he had no criminal intent at the time the car first went on to the foot, but the court held that deciding to leave the car there was a combination of act and intention, which meant he was guilty of the offence.

7. R v R, 1991

The law is constantly evolving to meet changing social attitudes. In this case, the House of Lords swept away the common law rule that a man could not be guilty of raping his wife. The previous rule was based on a 1736 pronouncement that:

By their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given herself up to her husband, consent which she cannot retract.

The House of Lords ruled that for modern times, marriage is a partnership of equals and any other suggestion was “quite unacceptable”.

8. The Belmarsh case, 2004

The Human Rights Act empowered judges to review acts of parliament, to check if they are compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. Using this power, the House of Lords ruled that a statute which allowed terrorist suspects to be detained indefinitely without trial breached the suspects’ human rights.

The case shows how modern courts ask not just whether government action is authorised by law, but also whether it is compatible with our rights. Parliament amended the law as a result.

In 2016, Gina Miller brought a case against the UK government, claiming that it couldn’t trigger Article 50 – and therefore Brexit – without an act of parliament. Ruling in Miller’s favour in 2017, the Supreme Court drew on the 1610 case of proclamations. So there’s no doubt that even the oldest cases still have the power to shape society today.