Safe sanitation and hygiene for the poor has never been more urgent than it is now in Yemen. In addition to chronic problems of diarrhoea among Yemeni children, the United Nations considered Yemen to be hit by the worst cholera outbreak in recent history in the modern times. It is a full-blown catastrophe, especially with 50% of health facilities not functioning due to conflict in the country. In 2021, 2.3 million cases of cholera in children under the age of five and more than a million cases of pregnant and lactating women with acute malnutrition were projected.

Insufficient access to WASH services is one of the major drivers of soaring malnutrition rates and pandemic waves. Social Fund for Development (SFD) pre-intervention surveys in more than 2,000 villages showed that:

- 80% of houses lacked appropriate sanitation,

- 20% didn’t have latrines at all, and

- 60% did have latrines that provide privacy, but were disposing wastewater into the open, either directly to the ground surface or to open cesspits.

The population projection of Yemen for 2020 was 29,825,968 and about 75% live in more than 100,000 scattered settlements. Most of these settlements are in the highlands of Yemen characterised by rugged terrain; hence, they are very difficult to access.

Focusing in, Bait Al-Amir village is located in the highland part of Yemen, 100 km south-west of Sana’a. The travel time to the village is 4 hours, of which 2.5 hours is through asphalt road and 1.5 hours through rugged road. As if this rough terrain is not enough, the outbreak of the war in March 2015 added another burden to access the village. Official security permission needs to be requested 3 days ahead of the visit and checkpoints on the way to the village add another hour onto the journey.

What was the starting point before the intervention?

In 2017, the Manakhah District Health Office issued a distress call that Bait Al-Amir had become a cholera hotbed.

A project officer from Sana’a SFD office visited the village in 2019 and assessed the situation. Human faeces were spread out around bushes and wastewater was flowing everywhere behind the houses and alleys. The village was a real focal point for spreading all sorts of waterborne diseases such as watery diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis B, polio and helminths. Hence, the village was included in the list of SFD’s subprojects financed by the German government.

The baseline data showed that the village had 60 houses and all of them were without appropriate sanitation. Out of the 60 houses:

- 27 houses had very basic dry latrines which allowed disease vectors to come into direct contact with human faeces,

- 10 houses had latrines that provide privacy, but were disposing wastewater to the open,

- the remaining 23 houses didn’t have latrines at all, so household members had to go outside to defecate behind bushes.

Women and girls suffered the most from the lack of a latrine at home, ignoring the call of nature all day until sunset. Then they would go in groups to defecate behind the bushes and prepare themselves for a long night without latrines at home. In emergencies, they defecated in plastic bags and threw them from the roofs to areas behind their houses.

The intervention

The intervention is part of SFD’s advocacy and promotion of the improved Yemeni traditional dry latrine as a suitable option for the water scarcity context of Yemen. The intervention included the following:

- improving 27 existing dry latrines and 10 existing pour flush latrines,

- building 8 dry latrines and 15 pour flush latrines,

- providing 60 household water filters,

- conducting hygiene campaign using CLTS tools.

The principles of EcoSan (collecting, isolating and reusing human faeces as fertiliser) were applied in both the dry and pour flush latrines.

A conditional grant procedure was used for implementation, where every household builds or improves its latrine under SFD’s supervising engineers and technicians, and payment is given for completed work items based on upfront agreed unit cost.

This method of implementation hits several goals in one, including providing job opportunities, increasing heathy life years, improving the environment of the community and protecting water sources of downstream communities.

The implementation started in the beginning of June 2021 with personal protective equipment for the beneficiaries and communication on safeguards and grievance mechanisms. The physical work started immediately and continued without interruption until completion at the end of August 2021. The total budget was 57,900 EUR, benefitting 450 people.

Environmental, social and health outcomes resulting from behaviour change

Khaled, one of the villagers, confirmed that they have now started using the latrines and feeling the benefits (ease of use and disappearance of environmental pollution, odours and insects). Two months after launching the service, the villagers felt a significant decrease in the incidence of children’s diarrhoea. Khaled remembered how faeces was washed through the village with the rain: “We used to memorise the names of medicines of frequent diseases to cure ourselves and our children, and we made them available at home all year round. The medicines cost us a lot in addition to the families who visit the capital city’s hospitals, and in doing so they spent huge amounts of money.”

Fatima is married with 4 children, the eldest is 11 years old. Her children often used to get boils on their skin from mosquito bites. Fatima comments, “We realised now more than before that our life without a latrine was dirty, unhealthy and undignified. It was dangerous because insects were transferring dirt to sources of drinking water and food that enter our bodies. Today we realise the real reasons behind the recurrence of diseases, especially COVID-19 and cholera, especially for our children”. She added: “I also used to bathe my children in the kitchen only once a month because some of them were affected by the cold waves entering from the openings. Now I bathe them once or twice a week in the bathroom without problems because the walls are sealed totally.”

The inclusion of people with disabilities

Najat (a 62-year-old woman) has a small family with an aged husband, a young son, and a disabled daughter Batol (16 years). Because of the complete atrophy of one of Batol’s hands and one of her legs, Najat had been carrying Batol on her back to the old latrine, encountering difficulties in cleaning and taking care of her personal hygiene. The problem had exacerbated as Batol grew, matured, and weighed more. She became in dire need of privacy for her sense of confidence and dignity, and minimum levels of capability and independence. This coincided with her mother becoming frailer with age, and the old latrine was not making any of this easier for the mother, or the daughter.

The latrine has now been improved and exceptionally provided with adequate equipment that helped Batol use all its components for all her needs, including bathing independently.

Najat comments, “Since the completion of the latrine, Batol is smiling more than ever. Now she is asking permission to spend a longer time in the latrine at her own as she enjoys comparing it with the previous primitive one such as tiles and tap/faucet water system and lack of odour.”

The supervising team discovered the disability of Batol, near the end of implementing this project and at the stage of finishing Batol’s family latrine. The main reason for this late discovery can be attributed to the highly conservative nature of the community and the tendency to hide disabled family from outsiders. Fortunately, the flexibility in SFD’s procedures allowed the modification of the latrine and the addition of supporting bars and plumbing fixtures to respond to Batol’s need. To strengthen equity in all SFD’s projects, a gender focal point was recently hired in the head office and there are plans and training courses in the way to achieve the principle “Leave No One Behind”.

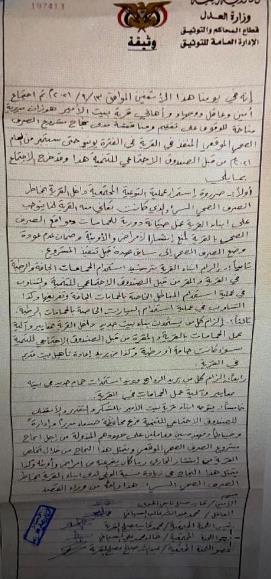

To encourage the sustainability of the intervention, a document was signed by the community leaders and government officials including the following commitments:

- Awareness-raising of the negative impacts of bad sanitation and bad behaviour shall continue, to prevent the spread of diseases, and prevent slippage to the pre-intervention

- All house owners must operate and maintain the latrines according to SFD’s guidelines

- Any new building shall include a latrine complying to SFD’s design

- Any new marriage agreement shall oblige the groom to build a latrine for his new family.