Towards transdisciplinarity – which route to take? Part II

Photo: Shutterstock

This next installment of the discussion on transdisciplinarity that began with this post focuses the discussion on the tension between the various imperatives within academia, how the Hub is measuring its progress on trans/interdisciplinarity and how this connects to research leadership.

What is the aspiration? Research Excellence or Global Development?

Elisa raises the realities of prevailing imperatives which mean that researchers also have to respond to funder and institutional expectations around research excellence:

While we are focusing on inter- and transdisciplinarity, we also need to be aware that policy-makers and other academics (but also non-academic partners) that will judge our work expect research excellence, which is still heavily assessed on a disciplinary basis. Hence the concurrent need to keep going “back and forth” to our disciplines, including to show how inter- and transdisciplinarity can add value to distinct disciplines in their own terms (and hopefully inspire others to take the inter- and trans-disciplinary route).

Jeremy acknowledged the perverse incentives that researchers face:

Yes, I can see the necessity of perpetuating the broken system for many. And making change beyond scholarly intent can be difficult1.

Rather than seeing the two aims as contradictory, the rationale of the GCRF appears to position inter/transdisciplinarity as a more effective means of problem solving and also of generating “globally influential research and innovation”2. We are expected to set our sights on both aims.

While being able to do both is increasingly seen as an asset, as Jeremy notes in the following excerpt, early career researchers in particular face a dilemma—develop a singular, authoritative voice within their discipline (in social sciences this often translates into publishing single author papers in prestige journals) or demonstrate their ability to co-produce work with other disciplines and with practitioners (often the insights that make into policy frameworks are not ones that attract the interest of journals). For ECRs to succeed in they essentially, should do both, often simultaneously.

Career establishment within a discipline seems to be a prerequisite for subsequent entry into the more transdisciplinary world. Td will always be mainly of a peripheral interest because of the discipline-based stagnation of Universities and their funders, and the journals and their discipline-based peers. GCRF might demand Id and Td approaches to combat intractability, yet if does not employ mechanisms to promote this, thus constraining “global innovation” to a limited pool which do not necessarily represent the optimum cohort to advance intractability. Sounds a bit like another disconnect!

It is worth noting that research on trans/interdisciplinarity illustrates that it has had mixed results. Not every problem benefits from interdisciplinary intervention3. Knowing this, means that the Hub can be strategic about where it directs holistic approaches.

Another issue is the politics of knowledge production. There is no guarantee that excellent evidence that is predicted to have impact will be taken up by the target audience-implementer. Researchers have to undertake often invisible relationship-building in order to have the desired impact. COVID 19 and climate change, two major crises for humankind, are lessons about the politics of knowledge and that validity can be informed by ideological perspectives about what counts as evidence (e.g. forecasting using quantitative modelling versus historical epidemiological case studies). Researchers can generate evidence that meets their disciplinary standards of robustness only to find that it is called into question in the rooms where decisions are made and even in the public sphere. The Hub has to reckon with the state of play in the context(s) in which it is embedded. For instance, the requirement that its research be ‘ODA (Overseas Development Assistance) compliant has implications for the design and conduct of research.

The importance of relationship-building for the uptake of evidence is a strong argument for transdisciplinarity. Including ‘implementers’ and ‘targets’ in the project design makes it less likely that they will distance themselves from eventual findings. Elisa is encouraged by various efforts within the Hub, particularly a webinar during World Ocean Week where Hub researchers explored the meanings and boundaries of transdisciplinary research:

Seeing more nodes earnestly pushing beyond inter-disciplinarity towards transdisciplinary approaches would be nice – that is why I like the WOW event as it was probing in a different direction.[…] there will still be a way to go to determine when where trans/interdisciplinary are useful/effective.

Elisa also notes that as the Hub is experimenting with these modes of research, it is also studying them:

The Hub is not stepping away completely from doing disciplinary (and in fact, also intra-disciplinary research). Reflecting on the limits of interdisciplinarity is also part of the research that is taking place within the Hub.

Various researchers within the Hub, like Michel Wahome, are evaluating the processes that generate inter/transdisciplinarity within the Hub. One assumption that is a primary concern of the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) programme of work is evaluating whether a challenge-centred and/or country-led approach allows researchers to deploy the elements of their expertise that are most relevant to solving identified problems. Underlying this question, is the more esoteric and long-lived debate into whether different ways of knowing and understanding the world can work together and produce synergistic findings. If realists and idealists focus on the same problem, can they agree on the solution(s)? Michel finds herself encouraged by participants in the Aarhus Neuro School who advise that transdisciplinary projects embrace the politics that come with these exercises as part of the experiment. They write (p 715):

We now interpret our awkward, and yet also somehow ‘successful’, experience as a sign of how we have learned to live with such alliances – even where they are difficult, or unhappy – to assist more marginal modes of knowledge as they seek to become both say-able and witness-able4.

One of the benefits of challenge-led research is that the proof is ultimately in the pudding, which presumably means that researchers can set aside their perspectival differences to produce good development outcomes.

Collaborative Leadership

The intention of the accompaniment that Megan Seneque, a social process and development professional, has been providing for the Hub is to help the Executive Team model internally the collaborative governance they seek to establish in global ocean governance across all the project sites. The Executive Team (ET) provides the Hub’s with its strategic direction. This has involved bringing together well-designed generative social process with the core work of the Hub, in order to help achieve the core purpose of the Hub.

The intended outcomes and outputs of this accompaniment include:

- An experience of collective leadership, collaborative emergent learning and collaborative decision-making.

- An experience of bringing to life the Hub principles and embodying the 6 characteristics of knowledge co-production and engaged scholarship that have been articulated by the Hub.

- The emergence of the Executive Team as a social-ecological system, modelling forms of collaborative governance appropriate for oceans research and governance; ones which reflect the realities of the Hub as a complex adaptive system.

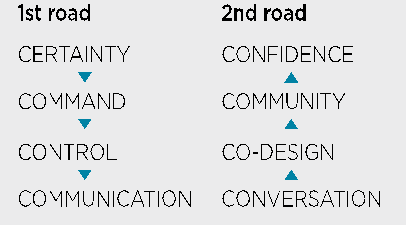

Creating the conditions for collective leadership is itself a form of transdisciplinarity. It requires a focus on what the Hub is trying to achieve as a collective, and then enabling each member of the ET to lead from where they are in order to achieve both personal and collective purposes. This is not traditional hierarchical leadership, characterised by power moves, but facilitative leadership that allows each person to lead from their particular role and make a contribution in relation to the whole. The work with the ET is intended to build relational accountability and collective leadership through understanding the strategic potential of all contributions to the Hub and the different roles of each in bringing about the systemic change that the Hub seeks.

The intentional design of ET meetings has been enable the shift from traditional content-based agendas to more generative conversation around questions, rather than ‘reporting’ on ‘activities’. Shifting patterns of interaction and traditional ways of organising is central to building capability for collective leadership. This allows for mutual exploration and learning together about the complexities of transdisciplinary collaboration and where it is appropriate in relation to discipline-based approaches and the purposes of the Hub. Making visible this exploration itself can make a substantive contribution to what is required to create the conditions for transgressive learning and trandisciplinary knowledge creation in relation to intractable problems/issues. MEL data about the Hub’s capacity to engage stakeholders and practice transdisciplinarity is transmitted not only to the Executive Team, but to the funder during the annual reporting process. While not everyone in the Hub might need to undertake transdisciplinary research, this approach towards leadership means that inter/transdisciplinary working is embedded in the rationales that guide Hub strategy.

Conclusion

While trandisciplinarity and disciplinary research excellence/innovation are characterised as mutually inclusive, there is an underlying contestation between the two. The result is that it often seems likes academics have to develop strong reputations within their fields before they can ‘safely’ build the skills for inter/transdisciplinary working. The growing acceptance of interdisciplinarity as creating valuable environments for problem-solving may alleviate the pressure to do both. Once various forms of knowledge and expertise have been integrated and solutions developed, buy-in, uptake and implementation often rely on the robustness not only of the evidence but of the relationships that have been developed. Thus, transdisciplinary outcome-driven researchers also have to develop skills in network building and collaborative leadership. Transdisciplinary projects benefit from an approach to leadership that builds relational accountability and collective leadership. The Hubs are ultimately experiments in how to transform academic research from an individual pursuit to a communal, problem solving effort.

References

Anderson, Warwick. “Postcolonial Specters of STS.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society 11, no. 2 (June 1, 2017): 229–33.

Bhambra, Gurminder K. “Sociology and Postcolonialism: Another `Missing’ Revolution?” Sociology 41, no. 5 (2007): 871–884.

Brazdauskaite, Giedre, and Danute Rasimaviciene. “Towards the Creative University:Developing a Conceptual Framework for Transdisciplinary Teamwork.” Journal of Creativity and Business Innovation 1 (2015): 49–63.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein. “Curiosity and the End of Discrimination.” Nature Astronomy 1, no. 6 (2017).

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham, N.C. ; London, Durham [NC]: Duke University Press, 2010.

Chilisa, Bagele. “Decolonising Transdisciplinary Research Approaches: An African Perspective for Enhancing Knowledge Integration in Sustainability Science.” Sustainability Science 12, no. 5 (2017): 813–827.

Chimhowu, Admos, David Hulme, and Lauchlan Munro. “A GCRF Proposal on a Strategic Network on New National Planning (S3NP) in the Global South,” 2017.

Fitzgerald, Des, Melissa M. Littlefield, Kasper J. Knudsen, James Tonks, and Martin J. Dietz. “Ambivalence, Equivocation and the Politics of Experimental Knowledge: A Transdisciplinary Neuroscience Encounter.” Social Studies of Science 44, no. 5 (2014): 701–721.

Glennie, Jonathan. “Why Haven’t Politicians Heeded the Wisdom of EF Schumacher? | Jonathan Glennie.” The Guardian, June 8, 2011, sec. Global development. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2011/jun/08/fritz-schumacher-economic-environmental-visionary.

Grandi, Fabio, Luca Zanni, Margherita Peruzzini, Marcello Pellicciari, and Claudia Elisabetta Campanella. “A Transdisciplinary Digital Approach for Tractor’s Human-Centred Design.” International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing: Transdisciplinary Approaches to Digital Manufacturing for Industry 4.0 33, no. 4 (2020): 377–397.

Harding, Sandra. “Postcolonial and Feminist Philosophies of Science and Technology: Convergences and Dissonances.” Postcolonial Studies 12, no. 4 (December 1, 2009): 401–21.

Kahanamoku, Sara, Rosie ’Anolani Alegado, Aurora Kagawa-Viviani, Katie Leimomi Kamelamela, Brittany Kamai, Lucianne M. Walkowicz, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Mithi Alexa De Los Reyes, and Hilding Neilson. “A Native Hawaiian-Led Summary of the Current Impact of Constructing the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea,” 20200103.

Klein, Julie. “A taxonomy of interdisciplinarity.” Nouvelles perspectives en sciences sociales 7, no. 1 (2011): 15–48.

Latour, Bruno. “The Recall of Modernity: Anthropological Approaches.” Cultural Studies Review 13, no. 1 (2007): 11–30.

Light, Ryan, and Jimi Adams. “A Dynamic Multidimensional Approach to Knowledge Production.” In Investigating Interdisciplinary Collaboration, edited by Scott Frickel, Mathieu Albert, and Barbara Prainsack, 127–47. Theory and Practice across Disciplines. Rutgers University Press, 2017.

Max-Neef, Manfred A. “Foundations of Transdisciplinarity.” Ecological Economics 53, no. 1 (April 2005): 5–16.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. Epistemic Freedom in Africa : Deprovincialization and Decolonization. Routledge, 2018.

Nowotny, Helga. “Prologue: The Messiness of Real World Situations.” In Investigating Interdisciplinary Collaboration, edited by Scott Frickel, Mathieu Albert, and Barbara Prainsack, 1–4. Theory and Practice across Disciplines. Rutgers University Press, 2017. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1j68m9r.4.

Scholz, Roland W. “Transdisciplinarity: Science for and with Society in Light of the University’s Roles and Functions.” Sustainability Science 15, no. 4 (July 1, 2020): 1033–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00794-x.

Seth, Sanjay. “Is Thinking with ‘Modernity’ Eurocentric?” Cultural Sociology 10, no. 3 (September 1, 2016): 385–98.

Strom, Mark. “Lead with Wisdom”. John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd, 2013.

Suchman, Lucy. “Anthropological Relocations and the Limits of Design.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40, no. 1 (October 21, 2011): 1–18.

UKRI. “Global Research Hubs Tackle World’s Toughest Challenges – UK Research and Innovation.” Accessed July 10, 2020. https://www.ukri.org/news/global-research-hubs/.