Abstract

Future thinking is defined as the ability to withdraw from reality and mentally project oneself into the future. The primary aim of the present study was to examine whether functions of future thoughts differed depending on their mode of elicitation (spontaneous or voluntary) and an attribute of goal-relatedness (selected-goal-related or selected-goal-unrelated). After producing spontaneous and voluntary future thoughts in a laboratory paradigm, participants provided ratings on four proposed functions of future thinking (self, directive, social, and emotional regulation). Findings showed that spontaneous and voluntary future thoughts were rated similarly on all functions except the directive function, which was particularly relevant to spontaneous future thoughts. Future thoughts classed as goal-related (selected-goal-related) were rated higher across all functions, and there was largely no interaction between mode of elicitation and goal-relatedness. A higher proportion of spontaneous future thoughts were selected-goal-related compared with voluntary future thoughts. In general, these results indicate that future thinking has significant roles across affective, behavioural, self and social functions, and supports theoretical views that implicate spontaneous future thought in goal-directed cognition and behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an in-depth discussion of conceptual differences between spontaneous and voluntary future thought, see Cole & Kvavilashvili, (2019b).

There are several phenomena that are related to spontaneous future thinking. For example, mind wandering is described as a shift in one’s attention away from events in the environment and towards mental content generated by the individual, and is often, but not necessarily, about the future (Smallwood & Schooler, 2015). Daydreaming is related to both mind wandering and spontaneous future thinking but generally involves withdrawing from the surrounding environment and moving one’s thoughts onto absent or imaginary events/objects. Importantly, daydreaming and mind wandering can involve volitional processes (Dorsch, 2015; Seli et al., 2016), whereas a cardinal property of spontaneous future thought is its unbidden nature (see Cole & Kvavilashvili, 2019a).

The principle underlying our decision to match the N size to a previous study was based on the fact that this study (Cole & Berntsen, 2016) which had effect sizes (ηp2) of 0.10—0.26 comparing selected-goal-related and non selected-goal-related future thoughts. This previous study had large enough effect sizes to find significant differences at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels. But because Cole & Berntsen (2016) included 32 participants in past and future groups, and we had only one future group, an N size of 32 was deemed adequate to find differences in a within-groups design.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this point.

Considering that one participant was male, it would be useful to ascertain the effect of mode of elicitation and goal-salience when this male is excluded; thus making our results generalisable to the female population. When this male was excluded, analyses of function ratings with the remaining 30 participants, with the same ANOVAs presented in “Functions” showed consistent main effects and interactions as with the male included. Thus, we conclude that the addition of this male did not affect our main analyses.

Although somewhat related, as both refer to goals, we believe that current concerns and the directive function are conceptually different. Current concerns refer to higher order goals whereas the directive function is centred around the pursuit of these goals (so the thoughts/actions required to achieve goals, see Klinger, 1975; Pillemer, 2003). Also, data from the study indicated that some of the current-concern related thoughts were not rated as 10 (highly) for the directive function. This indicates that these could be related but separable constructs. In fact, 16.18% of current concern related thoughts were rated low (< 3) on the planning function, 33.82% for the goal setting function, and 32.35% for the decision-making function.

References

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). Age-related changes in the episodic simulation of future events. Psychological science, 19(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02043.x.

Anderson, R. J., Dewhurst, S. A., & Nash, R. A. (2012). Shared cognitive processes underlying past and future thinking: The impact of imagery and concurrent task demands on event specificity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(2), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025451.

Armitage, C. J., & Reidy, J. G. (2012). Evidence that process simulations reduce anxiety in patients receiving dental treatment: randomized exploratory trial. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2011.604727.

Atance, C. M., & O'Neill, D. K. (2001). Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(12), 533–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01804-0.

Barsics, C., Van der Linden, M., & D'Argembeau, A. (2016). Frequency, characteristics, and perceived functions of emotional future thinking in daily life. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1051560.

Barzykowski, K., Radel, R., Niedźwieńska, A., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2019). Why are we not flooded by spontaneous thoughts about past and future? Testing the cognitive inhibition dependency hypothesis. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 83(4), 666–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1120-6.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Oettingen, G. (2016). Pragmatic Prospection: How and why people think about the future. Review of General Psychology, 20(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000060.

Benoit, R. G., Gilbert, S. J., & Burgess, P. W. (2011). A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(18), 6771–6779. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6559-10.2011.

Berntsen, D. (1996). Spontaneous autobiographical memories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10(5), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199610)10:5%3c435:AID-ACP408%3e3.0.CO;2-L.

Berntsen, D. (1998). Voluntary and spontaneous access to autobiographical memory. Memory, 6(2), 113–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/741942071.

Berntsen, D. (2009). Spontaneous autobiographical memories. An introduction to the unbidden past. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511575921

Berntsen, D., & Bohn, A. (2010). Remembering and forecasting: The relation. Memory & Cognition, 38(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.38.3.265.

Berntsen, D., & Hall, N. M. (2004). The episodic nature of spontaneous autobiographical memories. Memory & Cognition, 32(5), 789–803.

Berntsen, D., & Jacobsen, A. S. (2008). Spontaneous (spontaneous) mental time travel into the past and future. Consciousness and Cognition, 17(4), 1093–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.001.

Berntsen, D., Staugaard, S. R., & Sørensen, L. M. T. (2013). Why am I remembering this now? Predicting the occurrence of spontaneous (spontaneous) episodic memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 426–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029128.

Bluck, S., Alea, N., Habermas, T., & Rubin, D. C. (2005). A TALE of three functions: The self-reported uses of autobiographical memory. Social Cognition, 23(1), 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.23.1.91.59198.

Boyer, P. (2008). Evolutionary economics of mental time travel? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(6), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.03.003.

Bulley, A., Henry, J., & Suddendorf, T. (2016). Prospection and the present moment: The role of episodic foresight in intertemporal choices between immediate and delayed rewards. Review of General Psychology, 20(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000061.

Cole, S. N., & Berntsen, D. (2016). Do future thoughts reflect personal goals? Current concerns and mental time travel into the past and future. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(2), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1044542.

Cole, S. N., Barnes, M., Jones, T., & Elwell, C. (2019). What are the cognitive mechanisms underlying spontaneous future thinking? Manuscript in Preparation

Cole, S. N., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2019a). Spontaneous future cognition: The past, present and future of an emerging topic. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 83, 631–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-019-01193-3.

Cole, S. N., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2019b). Spontaneous and deliberate future thinking: A dual process account. Psychological Research. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-019-01262-7.

Cole, S. N., Staugaard, S. R., & Berntsen, D. (2016). Inducing spontaneous and voluntary mental time travel using a laboratory paradigm. Memory & Cognition, 44(3), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-015-0564-9.

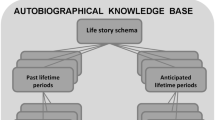

Conway, M. A. (2005). Memory and the self. Journal of Memory and Language, 53(4), 594–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.005.

Conway, M. A., Justice, L., & D’Argembeau, A. (2019). The self-memory system revisited: Past, present, and future. In J. H. Mace (Ed.), The organization and structure of autobiographical memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Conway, M. A., Loveday, C., & Cole, S. N. (2016). The remembering–imagining system. Memory Studies, 9(3), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698016645231.

Daniel, T. O., Stanton, C. M., & Epstein, L. H. (2013). The future is now: reducing impulsivity and energy intake using episodic future thinking. Psychological Science, 24, 2339–2342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613488780.

D'Argembeau, A., Lardi, C., & Van der Linden, M. (2012). Self-defining future projections: Exploring the identity function of thinking about the future. Memory, 20(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.647697.

D'Argembeau, A., & Mathy, A. (2011). Tracking the construction of episodic future thoughts. Journal of experimental psychology: General, 140(2), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022581.

D'Argembeau, A., Renaud, O., & Van der Linden, M. (2011). Frequency, characteristics and functions of future-oriented thoughts in daily life. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(1), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1647.

D'Argembeau, A., Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Collette, F., Van der Linden, M., Feyers, D., et al. (2010). The neural basis of personal goal processing when envisioning future events. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(8), 1701–1713. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21314.

Dorsch, F. (2015). Focused daydreaming and mind-wandering. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 6(4), 791–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-014-0221-4.

Dunkel, C. S., & Anthis, K. S. (2001). The role of possible selves in identity formation: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 24(6), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0433.

Finnbogadóttir, H., & Berntsen, D. (2011). Spontaneous and voluntary mental time travel in high and low worriers. Memory, 19(6), 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.595722.

Finnbogadóttir, H., & Berntsen, D. (2013). Spontaneous future projections are as frequent as spontaneous memories, but more positive. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(1), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2012.06.014.

Fleury, J., Sedikides, C., & Donovan, K. D. (2002). Possible health selves of older African Americans: Toward increasing the effectiveness of health promotion efforts. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 18(1), 52–58.

Gaesser, B., Keeler, K., & Young, L. (2018). Moral imagination: Facilitating prosocial decision-making through scene imagery and theory of mind. Cognition, 171, 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.11.004.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. American psychologist, 54(7), 493–503. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

Hall, S. A., Rubin, D. C., Miles, A., Davis, S. W., Wing, E. A., Cabeza, R., et al. (2014). The neural basis of spontaneous episodic memories. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26(10), 2385–2399. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00633.

Harris, C. B., Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2014). The functions of autobiographical memory: An integrative approach. Memory, 22(5), 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2013.806555.

Hoyle, R. H., & Sherrill, M. R. (2006). Future orientation in the self-system: Possible selves, self-regulation, and behavior. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1673–1696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00424.x.

Irish, M., & Piguet, O. (2013). The pivotal role of semantic memory in remembering the past and imagining the future. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00027.

Jeunehomme, O., & D'Argembeau, A. (2016). Prevalence and determinants of direct and generative modes of production of episodic future thoughts in the word cueing paradigm. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(2), 254–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2014.993663.

Johannessen, K. B., & Berntsen, D. (2010). Current concerns in spontaneous and voluntary autobiographical memories. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(4), 847–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.01.009.

Klinger, E. (1975). Consequences of commitment to and disengagement from incentives. Psychological Review, 82(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076171.

Klinger, E. (2009). Daydreaming and fantasizing: Thought flow and motivation. In K. D. Markman, W. M. P. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), Handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 225–239). New York: Psychology Press.

Klinger, E., Barta, S. G., & Maxeiner, M. E. (1980). Motivational correlates of thought content frequency and commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1222–1237. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077724.

Kvavilashvili, L., & Mandler, G. (2004). Out of one’s mind: A study of spontaneous semantic memories. Cognitive Psychology, 48(1), 47–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0285(03)00115-4.

Kvavilashvili, L., & Rummel, J. (2020). On the nature of everyday prospection: A review and theoretical integration of research on mind-wandering, future thinking and prospective memory. Review of General Psychology (Article accepted for publication)

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969.

McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (2000). Strategic and automatic processes in prospective memory retrieval: A multiprocess framework. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 14(7), S127–S144. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.775.

Munafò, M. R., Nosek, B. A., Bishop, D. V. M., Button, K. S., Chambers, C. D., Percie du Sert, N., et al. (2017). A manifesto for reproducible science. Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0021.

Nikles, I. I., Charles, D., Brecht, D. L., Klinger, E., & Bursell, A. L. (1998). The effects of current concern-and nonconcern-related waking suggestions on nocturnal dream content. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 242–255. https://doi.org.yorksj.idm.oclc.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.242

O'Donnell, S., Daniel, T. O., & Epstein, L. H. (2017). Does goal relevant episodic future thinking amplify the effect on delay discounting? Consciousness and Cognition, 51, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2017.02.014.

Peters, J., & Büchel, C. (2010). Episodic future thinking reduces reward delay discounting through an enhancement of prefrontal-mediotemporal interactions. Neuron, 66(1), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026.

Pham, L. B., & Taylor, S. E. (1999). From thought to action: Effects of process-versus outcomebased mental simulations on performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025002010.

Plimpton, B., Patel, P., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2015). Role of triggers and dysphoria in mind-wandering about past, present and future: A laboratory study. Consciousness & Cognition, 33, 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.01.014.

Pillemer, D. (2003). Directive functions of autobiographical memory: The guiding power of the specific episode. Memory, 11(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/741938208.

Prebble, S. C., Addis, D. R., & Tippett, L. J. (2013). Autobiographical memory and sense of self. Psychological Bulletin, 139(4), 815–840. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030146.

Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2009). Emotional valence and the functions. Memory & Cognition, 37(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.37.4.477.

Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2013). The reality of the past versus the ideality of the future: Emotional valence and functional differences between past and future mental time travel. Memory & Cognition, 41(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0260-y.

Rathbone, C. J., Conway, M. A., & Moulin, C. J. A. (2011). Remembering and Imagining: The role of the self. Consciousness & Cognition, 20, 1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2011.02.013.

Ruvolo, A. P., & Markus, H. R. (1992). Possible selves and performance: The power of self-relevant imagery. Social Cognition, 10(1), 95–124.

Schacter, D. L. (2012). Adaptive constructive processes and the future of memory. American Psychologist, 67(8), 603–613. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029869.

Schacter, D. L., Benoit, R. G., & Szpunar, K. K. (2017). Episodic future thinking: Mechanisms and functions. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 17, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.06.002.

Schlagman, S., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2008). Spontaneous autobiographical memories in and outside the laboratory: How different are they from voluntary autobiographical memories? Memory & Cognition, 36(5), 920–932. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.36.5.920.

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(8), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.05.010.

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331.

Smallwood, J., Schooler, J. W., Turk, D. J., Cunningham, S. J., Burns, P., & Macrae, C. N. (2011). Self-reflection and the temporal focus of the wandering mind. Consciousness & Cognition, 20, 1120–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.12.017.

Spreng, R. N., Stevens, W. D., Chamberlain, J. P., Gilmore, A. W., & Schacter, D. L. (2010). Default network activity, coupled with the frontoparietal control network, supports goal-directed cognition. Neuroimage, 53(1), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.016.

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. C. (2007). The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07001975.

Szpunar, K. K. (2010). Episodic future thought: An emerging concept. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(2), 142–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610362350.

Szpunar, K. K., Spreng, R. N., & Schacter, D. L. (2014). A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(52), 18414–18421. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1417144111.

Szpunar, P. M., & Szpunar, K. K. (2016). Collective future thought: Concept, function, and implications for collective memory studies. Memory Studies, 9(4), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698015615660.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 5, 7–24.

Thomsen, D. K. (2015). Autobiographical periods: a review and central components of a theory. Review of General Psychology, 19(3), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000043.

Warden, E. A., Plimpton, B., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2019). Absence of age effects on spontaneous past and future thinking in daily life. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 83(4), 727–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1103-7.

Waters, T. E., Bauer, P. J., & Fivush, R. (2014). Autobiographical memory functions served by multiple event types. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2976.

Wheeler, M. A., Stuss, D. T., & Tulving, E. (1997). Toward a theory of episodic memory: The frontal lobes and autonoetic consciousness. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 331–354.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our thanks to Chloe Kemsley for help in data collection, and Krystian Barzykowski for helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jessica Duffy declares that she has no conflict of interest. Scott Cole declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of York St John University ethics committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Future thought characteristics questionnaire (Part 1).

Appendix B

Future thought characteristics questionnaire (Part 2).

Appendix C

Examples of selected-goal-related and selected-goal-unrelated future thoughts.

Example 1: Selected-goal-related spontaneous future thought.

“Shopping for Christmas gifts with my stepdad” (Female, 18).

Relevant current concern: Finishing Christmas shopping.

Example 2: Selected-goal-related voluntary future thought.

“Someone breaking my trust and hurting me” (Female, 18).

Relevant current concern: To try and talk with and meet new people.

Example 3: Selected-goal-unrelated spontaneous future thought.

“I pictured myself in a wedding dress getting married. Actively thinking about future goals” (Female, 20).

All five current concerns: (1) spend more time with friends, (2) make more time to see boyfriend, (3) need to do more reading for university, (4) I am proud of myself for reaching 36-point target on SONA, (4) I am excited to start my new job in summer.

Example 4: selected-goal-unrelated voluntary future thought.

“Picking the phone up to my mam calling and asking about my day” (Female, 19).

All five current concerns: (1) finding a good job, (2) have a family, (3) travel, (4) find a nice house, (5) get my degree.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duffy, J., Cole, S.N. Functions of spontaneous and voluntary future thinking: evidence from subjective ratings. Psychological Research 85, 1583–1601 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-020-01338-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-020-01338-9