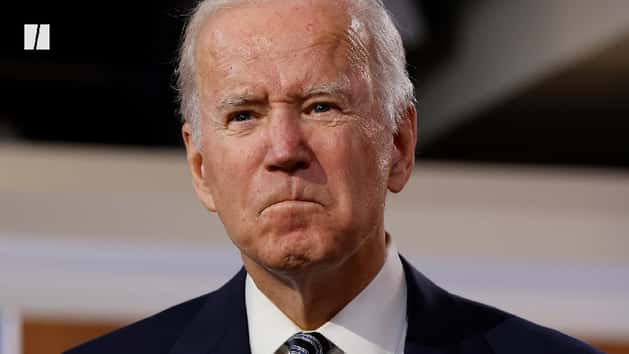

WASHINGTON – Inflation has become a top political problem in Washington, damaging President Joe Biden’s standing with voters and grinding his domestic policy agenda to a halt.

On Thursday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that compared to last year, consumer prices in January had risen at the fastest rate in decades. Democrats are already bracing themselves for the political hit that they may take in the midterm elections.

But on every other measure besides the consumer price index, the economy is actually doing incredibly well. There’s strong growth, unemployment at just 4%, and employers adding half a million jobs each month.

As Biden noted on Thursday, the past year has been “the greatest year of job growth in history.”

But in politics, apparently, inflation trumps jobs. Even in 2013, amid high unemployment and persistently low inflation, a huge majority of voters said rising prices were either a very big or moderately big problem.

The Federal Reserve, too, has historically been more concerned with inflation than unemployment. The Fed is now poised to tank the strong jobs market in order to slow price growth, an outcome that would hit society’s most vulnerable workers the hardest.

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) made the potential tradeoff clear Thursday when he called on Democrats to abandon their social policy dreams and for the Federal Reserve to throw cold water on the economy.

“It’s beyond time for the Federal Reserve to tackle this issue head on, and Congress and the administration must proceed with caution before adding more fuel to an economy already on fire,” Manchin said in a statement reacting to Thursday’s report that year-over-year inflation hit 7.5% in January ― the highest rate since 1982.

The early ’80s offer an unsettling parallel. The Federal Reserve inflicted major collateral damage when it subdued inflation, with higher interest rates causing a recession that threw millions of people out of work, resulting in 10% unemployment for nearly an entire year. And that’s an inflation success story.

The overall situation is much different today than in 1982; back then, the economy had struggled with both high unemployment and rising prices for much of the previous decade, and the Fed sought to prove it would stick by its tighter monetary policy even amid heavy job losses.

Manchin told HuffPost higher rates wouldn’t necessarily cause a recession today since our economy is much stronger than the one confronting the Fed in 1982. (Price spikes also preceded many prior recessions.)

“We’re not in a recession with a heated economy,” Manchin said. “They had high unemployment [and] a sluggish economy. We don’t have that.”

The Fed has a “dual mandate” to achieve stable prices and maximum employment by pushing interest rates up or down in order to encourage or discourage consumers and businesses to borrow and spend money. Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell said in December that the Fed might have to raise interest rates “before achieving maximum employment” this year.

“We would not, in any way, want to foreclose the idea that the labor market can get even better,” Powell said. “But, again, with inflation as high as it is, we have to make policy in real time.”

It’s possible the Fed could tame inflation without hurting employment, though analysts said such a good outcome would be more difficult in light of Thursday’s bad price report. It’s likelier that higher unemployment is the price we pay for lower prices.

But not everyone pays the same amount. When there’s a recession, most people don’t lose their jobs. The pandemic caused historic job losses, for instance, with 26 million unemployed at some point in 2020 ― just 15% of the workforce, 10% of the adult population.

Losing a job can be ruinous to individuals, and it’s the most vulnerable workers who are most affected.

“Unemployment is borne disproportionately by lower-wage workers with fewer formal credentials and disproportionately by workers of color,” Josh Bivens, research director for the Economic Policy Institute, said in an email.

Bivens’ research has found that low unemployment is crucial for blue-collar wage growth, reducing income inequality and shrinking racial disparities in earnings. It makes sense: If employers have fewer unemployed workers from which to recruit job candidates, then workers will have more bargaining power. And if the Fed slackens demand for workers, Bivens argues, then it will be harder for workers to demand higher wages.

Economists still debate what’s causing the current burst of inflation, since some price pressures resulted from pandemic-related supply constraints. Another contributor could be stimulus checks and other measures Democrats have taken, which also have kept unemployment and poverty low. It’s likely that when the government updates the poverty rate this year that 2021 saw historically low levels of material hardship, especially for children.

Consumer sentiment has nevertheless cratered. Inflation is in the news every day, making price changes more salient to consumers who are already predisposed to believe inflation is a problem.

“The media are hyping the bad news on inflation, while largely ignoring the very positive aspects of the economy,” Dean Baker, co-founder of the liberal Center on Economic and Policy Research, said in an email. Baker has argued that inflation largely reflects temporary supply constraints.

“When we go the grocery store, maybe we pay 5 cents more for a gallon of milk. Most likely we don’t give it too much thought,” Baker said. “But, if we turn on the news and hear the reporters telling us that milk prices are up 10% year-over-year, then we might think, ‘Yeah, I paid more for milk today.’”

For Manchin and Republicans, the debate is over, and record job growth is not worth record inflation. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) told HuffPost about how inflation is more noticeable than unemployment in people’s lives.

“When people are talking about things around their dinner table, they may talk about somebody that they know that has lost their job, but not everybody around that dinner table has,” Murkowski said. “Everybody around that table has been impacted by the cost of goods.”