A fruit and vegetable stand in Kampala, Uganda. Photo: Arne Hoel / World Bank

A fruit and vegetable stand in Kampala, Uganda. Photo: Arne Hoel / World Bank

Over the past few decades, Africa’s food import bill has more than tripled, reaching about US$35 billion a year. Much of this imported food could be produced locally, creating much needed jobs and incomes for nations’ youth and smallholder farmers. Or, with better regional food market integration, the food could be imported from other African countries, creating employment among neighbors.

In a recent Jobs Note, “Agriculture, Jobs, and Value Chains in Africa,” we explore how inclusive value chain development (iVCD) — in addition to more investment in rural public goods — could help Africa keep up with growing food demand and create more better jobs.

Many constraints mean a multi-pronged approach

There is no single overarching reason for Africa’s growing food imports. Underutilization of farm labor, shrinking farm size, and low output per hectare (low yields) all combine to keep smallholder output and earnings low. They follow seasonality in rainfed agriculture, rising population pressure, and limited or uncertain access to technology and more remunerative markets.

Interventions of the past, such as the popular smart input subsidy programs of the late 2000s, have not been effective. They addressed only one of the constraints. More integrated and pragmatic approaches are needed instead. That’s why countries and donors are increasingly pursuing iVCD, inspired in part by successes in Latin America.

What is inclusive value chain development?

iVCD contractually links smallholder producers with other value chain actors. Buyers can then secure higher volumes of better quality. They need this to access the more remunerative markets or to operate their plants at scale. Producers receive access to credit, agronomic knowledge, and a reduction of production, price and/or market risk.

Empirical evidence suggests that such arrangements can boost smallholder incomes by 20 to 50 percent. Women often benefit from wage job creation as well as improved labor conditions. But success is not guaranteed. Regular monitoring of the producer-buyer relation, involvement of third-party financing and producer co-financing, as well as capacity building of the actors over an extended period all help. As in micro-finance, the poorest often do not participate.

The iVCD approach is already underway in some African countries. One well documented example concerns the export-oriented horticulture estate farms in Senegal. But many other projects, focused on supplying the domestic market, have also been initiated, such as the Inclusion of Rural Youth in Poultry and Aquaculture Value Chain in Mali.

Often, such linkages between producers and buyers, or other actors in the chain, are brokered and supported through third-party intermediaries such as governmental and non-governmental organizations in a “Productive Alliance.”

Experimenting with iVCD in staples

Despite demonstrated promise for non-staple cash crops and products with potential for high value addition, such as dairy and meat, contract arrangements tend to be less suitable for staple crops (cereals, roots, and tubers). Their homogenous characteristics leave little room for quality upgrading and value additions — for example through production of processed foods such as chips or juice. This reduces the potential for a price premium needed to tie both parties into an incentive-compatible contract. Yet, cereals make up about one third of Africa’s food imports and an accelerated increase in staple crop productivity is indispensable for food security and the transformation of jobs in agriculture.

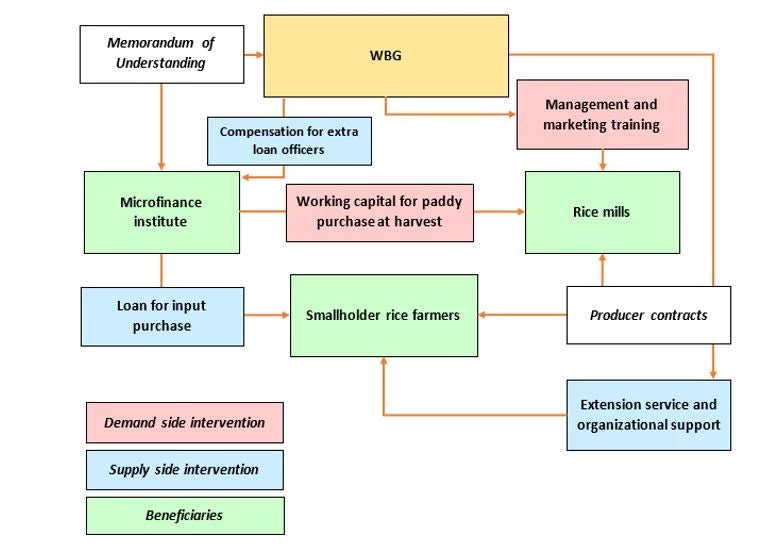

Figure 1: Contracting smallholder rice producers in Côte d'Ivoire

More recently, income growth and urbanization are adding complexity to quality and quantity requirements for certain staple foods. Urban consumers, for example, want an assured supply of higher quality rice, while higher quality sorghum is becoming an important ingredient for brewers to supply their growing urban markets. This has given rise to iVCD initiatives in some staple crops, such as rice in Côte d’Ivoire (Figure 1).

Nonetheless, for the reasons mentioned above, to raise staple crop productivity, there must especially be more and sustained investment in rural public goods such as agricultural research and development, extension, irrigation, and rural infrastructure. African governments have only been spending 3-4 percent of their total spending on agriculture since the 1980s compared with around 8 percent in East Asia.

The way forward

There are still many operational questions on how best to support iVCD. Thus it remains unclear, for example, whether smallholders are more likely to benefit from VCD when the contracting entity is an SME or when it is a more financially powerful domestic and international firm?

To turn Africa’s growing food imports into a domestic job generating engine, continued experiential learning in iVCD is called for, as well as more investment in agricultural and rural public goods , especially for its staples.

This blog is based on the Agriculture, Jobs, and Value Chains in Africa Solutions Note, published in April 2020. This is the fifth post in a blog series based on research and evidence from the World Bank Jobs Group’s Solutions Notes. The Solutions Notes synthesize findings from the Jobs Umbrella Multidonor Trust Fund (MDTF)-funded activities and other sources based on research, evaluations, pilots, and operations. Each Note succinctly analyzes efforts and challenges, and provides an evaluation of what has worked, and what does not.

The first fourposts in the series include:

- Promoting a Gender-Inclusive Labor Force Blog 1: Five ways to make skills training work for women

- Promoting a Gender-Inclusive Labor Force Blog 2: Five strategies to address employment hurdles faced by young Syrian women refugees

- Promoting a Gender-Inclusive Labor Force Blog 3: Six strategies to increase young women’s access to digital jobs

- Jobs Solutions Note Blog 4: Adapting jobs policies to technological change

Join the Conversation