The discovery of the double helix molecular configuration of DNA, a milestone in modern science, was reported 65 years ago this week in the journal Nature by American Jim Watson and Briton Francis Crick.

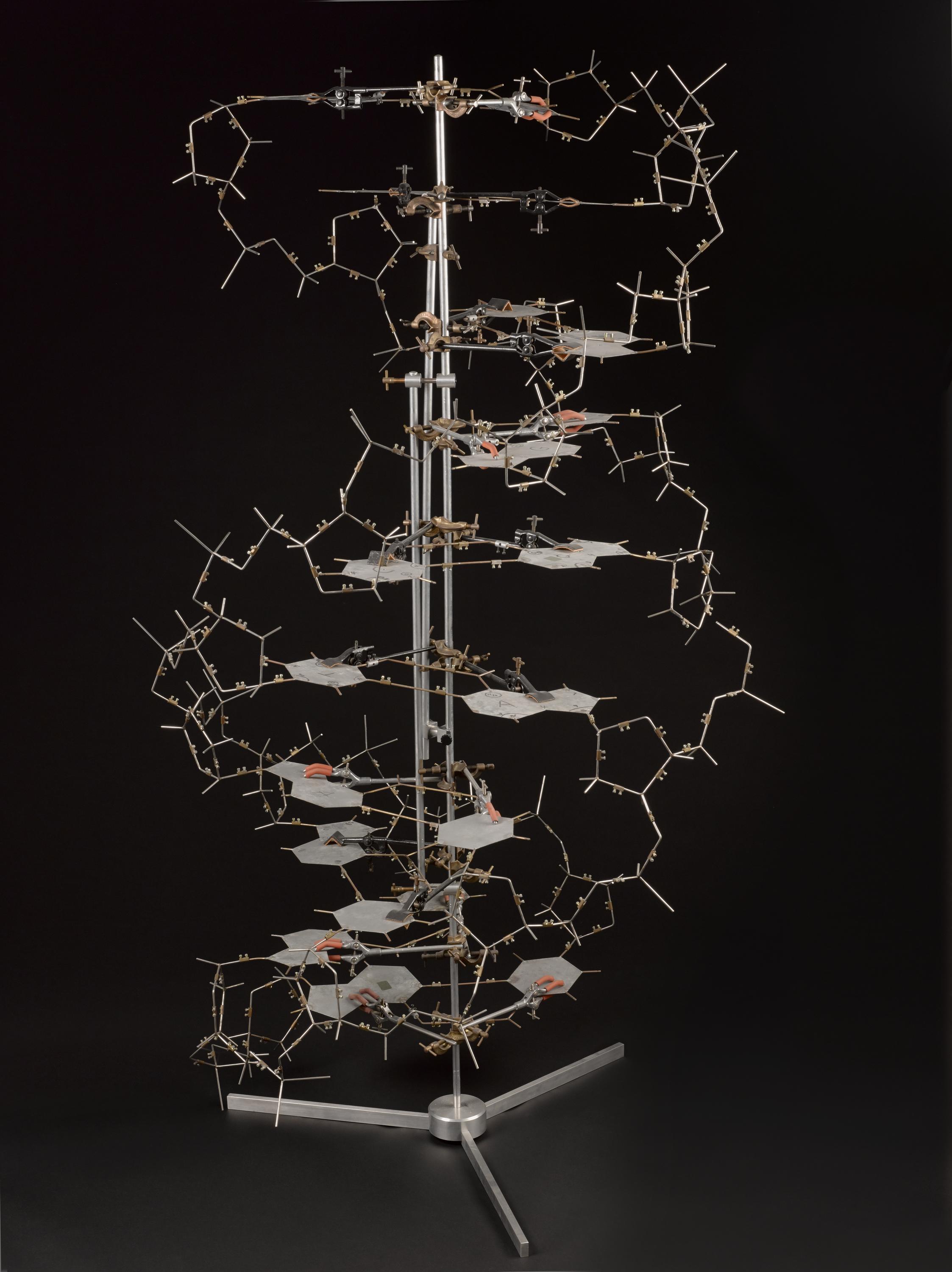

Jim Watson visited the Science Museum to mark the anniversary, see his original molecular models now held by the museum, and discuss the shock-waves that are still being sent out by his momentous 1953 discovery, from gene editing to developing new cancer treatments.

For many scientists, the discovery of the structure of DNA by this Cambridge-based team was only the beginning. It paved the way for new research in areas such as gene therapy for inherited diseases, the sequencing of the human genetic sequence – genome – and biotechnology.

‘That the essence of DNA came in less than one and a half years after I came to Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory, in the early fall of 1951, was more than wonderful,’ recalled Watson in a recent speech. ‘Within a day of our first meeting, I saw the then 35-year-old Francis Crick as extraordinary, not only through his brains but in his basic kindness, warmly treating me like a younger brother that had to be looked after.’

Earlier studies had shown that DNA is composed of building blocks called nucleotides consisting of a deoxyribose sugar, a phosphate group, and four nitrogen bases — adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). Phosphates and sugars of adjacent nucleotides link to form a long polymer.

One Saturday morning in February 1953, the race to determine how these pieces fit together in a three-dimensional model of the double helix was won by Watson and Crick.

Later that day, at the nearby Eagle pub, Crick supposedly declared that they had discovered the secret of life. Their discovery marked a milestone and set about revolutions in medicine, society, the environment and information processing.

Watson’s racy personal account of the discovery, The Double Helix (1968), became a bestseller and caused sensation for its candor. It is listed by the Library of Congress as one of 100 ‘Books That Shaped America’ and has now been published as ‘The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix.’

In the book, which celebrates its 50th birthday this year, Watson described the cast of characters in the race to the helix, notably Maurice Wilkins (with whom they would share the Nobel prize) along with Lawrence Bragg, Jerry Donohue, Rosalind Franklin, and their rival in America, Linus Pauling.

It was Wilkins’ pioneering X-ray studies of DNA which had first excited Watson. Wilkins and another key figure in the story, Rosalind Franklin, worked at King’s College, London. Franklin’s PhD student Raymond Gosling took Franklin’s X-ray photographs of DNA. Numbered 51 and taken in May 1952, it revealed a black cross of reflections, and would prove the key to unlocking the molecular structure of DNA, revealing it to be a double helix.

On leaving King’s College, Franklin gave all her data to Wilkins who then showed photograph 51 to Watson. Watson recalled the image was a revelation, because it ‘was so perfect’ and provided insights into the relationship between the bases (the chemical ‘letters’ of the genetic code, which form a ladder like structure inside) and the supporting structure of phosphate groups.

The molecular structures for the bases they used in their models of this structure were corrected one Thursday by quantum chemist Jerry Donohue, who shared an office with Watson and Crick. That insight proved essential, Watson told me, for his recognition of ‘base-pairing’ and for building one turn of the double helix the following Saturday on a table in the middle of their office.

The helical DNA structure came as an epiphany, ‘far more beautiful than we ever anticipated,’ said Watson, because the complementary nature of the letters of DNA (the letter A always pairs with T, and C with G) instantly revealed how genes were copied when cells divide: this was the long-sought mechanism of inheritance.

In 1962, four years after Franklin’s death due to cancer at age 37, Watson, Crick and Wilkins shared a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Between 1988 and 1992, Watson helped establish and served as first director of the US National Institute of Health’s Human Genome Project, to read every ‘letter’ in the human genetic code. In 2007, Watson and his rival in the race to sequence the human genome, Craig Venter, became the first to have their entire genetic code sequenced this way.

Watson celebrated his 90th birthday earlier this month with a gala piano concert and dinner at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on the East Coast of America, which Watson’s leadership turned into one of the world’s principal centres of biology, focusing on cancer genetics.

Eight Nobel laureates and many other giants in the worlds of biotech, genetics and scientific publishing were among the 400 guests gathered to toast his contributions to science and society.

He told them: ‘Key molecular biologists will soon be viewed by history as important as those great physicists of the 20th century who gave the world relativity, quantum mechanics, and nuclear energy. The Molecular Biology that has followed the 1953 finding of the Double Helix has been more than extraordinary. Even today we still move fast and furious in seeking out fundamental biological truths.’

He also gave a pledge that ‘I can and will remain active in fighting cancer as long as my brain remains functional.’

‘Further greatness in cancer research will likely only come through the development of drugs that give lifetime cures for the vast majority of its victims,’ he said. ‘Much reassuring me are two largely still untested classes of anti-cancer agents that block key features of malignant cells.’

One class of drugs on entering ‘cells generate cancer cell killing amounts of reactive oxygen species like superoxide and hydrogen peroxide.’ The second consists of ‘selective small micro (µ) RNAs’, which block key aspects of cancer cell metabolism: ‘these have the potential of killing much, if not virtually all, of today’s chemo-resistant cancer cell killers.’

Watson also mentioned his two top moral heroes, Bernie Sanders and Pope Francis, alluding to his recent interest in the genetics of human nature, notably the extraordinary extent to which humans cooperate. He told me: ‘”Evolution of ethical behaviour,” you know it is not a bad title for a book.’

This year Jim and his wife Liz celebrated their 50th year at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, on the North Shore of Long Island, along with their 50th wedding anniversary.