"Where we see people facing systematic discrimination or becoming targets of violence simply because of who they are, because of their identity, we must act – both to defend those at immediate risk and those who could be in jeopardy in the future. By promoting a culture of peace and non-violence that includes respect for diversity and non-discrimination, we can build societies that are resilient to the risk of genocide."

United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres

Objects and Artefacts

The objects in this exhibition reflect the lives of their one-time owners - their childhoods, their homes, their cultures – and the impact of war, trauma, displacement and exile on these lives. The objects survived the Holocaust, genocide and other atrocity crimes in Cambodia, Srebrenica and Rwanda. The objects are remains from a lost world. Dislodged from their original surroundings, these seemingly ordinary objects are now storytellers. They represent futures that were forever altered.

A call to Action

The United Nations was established over 75 years ago in response to the atrocity crimes committed during the Second World War. Preventing genocide remains as critical today as it ever did. This exhibition is a call to action and reminds us of the need to build a world in which justice prevails, and in which all people are equal in dignity and in rights.

In 1948, genocide was recognized as a crime under international law by the United Nations General Assembly with the adoption of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This was the first ever human rights treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. The Convention’s preamble recognizes that “at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity” and that international cooperation is required to “liberate humankind from such an odious scourge”. Genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law.

Image and Memory

Over a decade ago, photographer Jim Lommasson began working on a collaborative photographic and writing project with Iraqi and Syrian refugees to the United States, based on the objects they brought with them to this country. Survivors or their family members were asked to reflect through creative expression on the white background of the photographs of the objects, their memories attached to the object. This process allowed autobiographical narratives to become collective history. The objects carry with them stories of survival of incomprehensible inhumanity. The voices of survivors and their families illuminate the experiences that are shared despite differences of time and place: experiences of resilience, courage, the fragility of life, family history, and hope for the future. This exhibition is inspired by the original exhibition of the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center, and the images taken by photographer Jim Lommasson for his work with the Center in 2018. In the current exhibition, the images related to the Holocaust and the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda were taken by photographer Jim Lommasson. The images related to the genocides and atrocities in Cambodia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were provided by the Documentation Center in Cambodia, the War Childhood Museum Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Remembering Srebrenica.

This exhibition is a joint project of the Department of Global Communications and the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, together with the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center, the War Childhood Museum Bosnia and Herzegovina, Remembering Srebrenica, and the Documentation Center of Cambodia. The original exhibition Stories of Survival: Object. Image. Memory. on which this exhibition is based is a project of the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center and photographer Jim Lommasson.

THE HOLOCAUST

Coming to power in Germany in 1933, the Nazis implemented their racist agenda. Their targets included Jews, people with physical and mental disabilities, Germans of African descent, Roma and Sinti, homosexuals, and Slavs. Antisemitic persecution intensified after Germany invaded Poland in 1939, triggering the Second World War, and followed shortly by the invasion of the East of Poland by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The Germans isolated Jews in ghettos and deported them for slave labour.

With the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Nazi mobile killing units (Einsatzgruppen) and local collaborators began to murder Jews systematically. To relieve the stress on the killers of the face-to-face murder of women, children and men, the regime established annihilation sites equipped with lethal gas chambers. And it sought to erase Jewish family life, culture, and religious tradition. The Allied Forces defeated Nazi Germany and its allies in 1945.

Only one-third of Jewish men, women and children in Europe survived the Holocaust.

Ursula Meyer

(Delmenhorst, Germany, December 2, 1919 - Bremen, Germany, May 11, 1982)

Ursula Meyer’s Teddy Bear. Bremen, Germany, ca. 1925. On loan courtesy of the Walter and Gisela Hesse family. Photo/Jim Lommasson. Reflections by Marianne Hesse, niece of Ursula

With storm clouds gathering on the horizon, my aunt’s teddy bear was buried in a backyard for safekeeping.

My aunt and grandfather weathered the torrent and returned to Germany after three years in Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. After learning of the damage caused by the deluge, my aunt and grandfather wrote to my mother in America informing her that Tante Regine, Onkel Siegfried, Georg, Tante Toni, Hugo and his two sisters and Onkel Moritz and his family had been engulfed by the surge.

In the aftermath of the storm, my aunt was reunited with her childhood teddy bear."

Marianne Hesse

Ursula (far left) and the Meyer family

Mossek (Morris) Nortman

(Sosnowiec, Poland, September 3, 1913 - Miami Beach, Florida, January 1991)

Mossek and Ruchel (Rose) (France, ca. 1949-1952)

Rose (Ruchel) Nortman was 1 of 6 children born to Motke and Temman (Wiedling) Jungerman, in Volbrum, a small town in the southwest of Poland. When Rose’s father died, the family moved to the larger town of Sosnowiec where Rose met her future husband, Moszek Nuchman, who became Morris Nortman in this country.

Morris, the son of a well-respected Jewish scholar, met Rose at a dance and, over the objections of his mother, fell in love. The couple married twelve days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939.

When Morris’ sister’s family was murdered by the Nazis and he was conscripted for forced labor, he escaped. Rose and Morris then tried to make their way to Lvov in southeastern Poland, where a relative lived.

That was the last time that Rose saw her mother, sister Manya, and brother Herschel, who were murdered by the Nazis. In the summer of 1943, after being expelled to Siberia, the two spent several weeks on a boxcar with 120 other people surrounded by the stench of human waste and death. When the boxcar arrived in Siberia half of those that boarded in Lvov were dead.

Life in Siberia was terribly taxing but the Nortmans survived the barren, desolate location and cases of malaria to see the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Mossek (Morris) Nortman’s Laissez-Passer Travel Document. (France, 1947). On loan courtesy of Michael Nortman. Photo/Jim Lommasson Reflections by Michael Nortman, grandson of Morris

Judy Katz

(Satu Mare, Romania, 18 February 1930 – Glenview, Illinois, 9 March 2016)

Judy Katz’s Scarf. Germany, mid-20th century. Gift of Judy and Harold Katz. Photo/Jim Lommasson. Reflections by Jack, Larry, and Lila Katz, children of Judy

It was always in Mom’s dresser drawer. She never took it out. We never saw it, but it meant something to Mom. It kept her memories alive from before the camps. There is something special about this scarf that was special to her. We will never know. Lila saw it only once many years ago. Mom gave it to the museum so that people will know how something as small as a piece of fabric, can have special meaning, when everything else has been taken away from you. We will never know the story behind the scarf. We can only imagine."

Jack

Mom was wearing it when the family ARRIVED at Bergen-Belsen. She was wearing it when her mom PUSHED HER into the other line, where Mom’s older sister Debbie was. That was the line that LED TO LIFE."

Larry

Somehow throughout Mom’s time in the camps, this scarf survived as she did. It was her only link to life before the Shoah; to life as she remembered it. Mom survived and the scarf survived along with her."

Lila

Judy Katz, aboard the S.S. Marine. Marlin, 1947.

CAMBODIA

Between 1975 and 1979, under the Khmer Rouge regime, an estimated 1,5 to 2 million people died as a result of starvation, forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) have classified these acts as crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

In November 2018 the ECCC declared that the Khmer Rouge regime committed genocide against the Cham Muslim and ethnic Vietnamese minorities by implementing and executing a policy to target religious and racial groups with an “intent to establish an atheistic and homogenous society without class division by abolishing all ethnic, national, religious, racial, class and cultural differences”.

It is estimated that 36 percent of the reported pre-war Cham population of 300,000 died under the Khmer Rouge regime, while up to 90 percent of the 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese population in Cambodia was forcibly displaced to neighbouring Vietnam and up to 20,000 killed.

Keo Chhoeun

Photo/DC-Cam Collection of Khmer Rouge Victims Belongings

Keo Chhoeun, whose beard/moustache remover is featured in the exhibition, was a former National Volleyball and Tennis Champions and an official of the National Bank of Cambodia from (circa) 1968 -1975. He also ran for member of parliament of Takeo province against a senior state official, In Tam, in 1969. Photo of Keo Chhoeun dated 1969.

Photo/Try Socheata, circa late 1975. DC-Cam Collection of Khmer Rouge Victims Belongings

This beard/moustache remover was hand-made by Keo Chhoeun. who disappeared during the purge at Preah Neth Preah commune of Khmer Rouge's region 5 in 1978. His sister, Keo Nann, who is now 96 years old, kept this beard/moustache remover for over 40 years before she handed it to the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam).

Kong Sarifas

(Cambodia, 1970s)

Kong Sarifas with her daughters. Photo/DC-Cam Collection of Khmer Rouge Victims Belongings

When I was young, I lived with my older sister in Phnom Penh, and sold cakes in my spare time. One man often bought my cakes; sometimes, he bought all of them at once. One day he asked some elderly people to come and ask for my hand in marriage. It took eight months for me to agree to his proposal. I was only 13 years old and did not even know how to tie my hair into a bun. After we got engaged, he tried to push me to marry him as soon as possible. But I told him I would not get married until I learned how to cook. When we were engaged, he worked as a goldsmith while I wove silk at my home.

His family had an above-average income because they were merchants. After we were married, we lived at my sister’s house for a year. I stopped selling cakes and began mending fishing nets instead. Although we barely saved any money, we had enough food to eat each day."

My sons Yousib and Smael lived in Phnom Penh in the early 1970s; both of them were fishermen. Smael had beautiful curly hair that he did not have to comb at all. He was more handsome than his older brother Yousib. Yousib was afraid of having curly hair, so he used to comb it down many times each day. Both of my sons were educated men and brilliant students, especially Smael. They could read and write Khmer, Cham [the language of Cambodia’s Muslim community], Arabic, and Malaysian. Smael also studied magic with a teacher in Phnom Penh; he learned how to disguise himself and how to change the trajectory of a bullet.

Of my two sons, Smael was never scared of anything, not even ghosts or bullets, while Yousib was afraid of everything. I remember clearly the day when Smael took my clothes and put them on. He said, “I want to try on your clothes because I am afraid that I might be separated from you, mother.” I felt sad at his words; it seemed like a sign that one day my sons and I would be separated."

We moved back to Khleang Sbek Village in Kandal Province during the Lon Nol regime. By 1973, the fighting grew worse there, so we hired a car and went to Chraing Chamreh. All of the villagers left, not just my family. But after a while, my husband felt bad about losing his house, so he took three of our children –Yousib and Smael, and my daughter Mari – back to Khleang Sbek so they could fish; he said there was nothing for him to do in Chraing Chamreh. Later I went to Khleang Sbek so I could ask my husband and children to come back. However, he said he and our sons would not return, but that I could take Mari back with me. We left and reached Chraing Chamreh in the evening. The following morning all the roads were cut off and I never saw my husband or sons again.

Mari and I then went to Phnom Penh and stayed with my younger brother who was a colonel in the army. He told us to pack our belongings and leave the city because the situation in Phnom Penh was getting worse.

Before leaving, I wanted to return to Khleang Sbek and find my husband and sons, but the Khmer Rouge soldiers would not allow it. So my younger brother, daughter and I left Phnom Penh for Takeo Province.

In Takeo, we lived in many villages in Bati District. Wherever we went, they no longer allowed us to live with the Muslim community, and we were the only Chams in the village. We had many difficulties with eating, as our religion did not allow us to eat pork. Some people with bad intentions tried to make us eat pig meat.

In Bati District, the Angkar forced me to carry earth. Soon my eyes swelled up and my skin became yellow. My daughter could hardly recognize me. The Angkar then ordered Mari to join a children’s mobile unit. Seeing I was sick, my daughter dared to tell the unit chief that he should not force me to go to work any longer, pointing out that I was an old lady. We were lucky because the Angkar let us fix fishing nets instead. We also got to eat a lot because the fishermen often stole fish and gave them to us.

In 1978, we decided to run away because we could not stand starving any longer. But the cadres caught us and ordered us to live in another village, where they assigned Mari to dry beans. She could not stand this work and kept fainting. Seeing her like that, the unit chief sent Mari to prison for a short while and then released her. But then our old village chief wrote a letter asking that we be sent back. I refused to go and told the cadres that they should kill me right then rather than send me back. He replied that the Angkar just wanted me to go back to fix fishing nets because we were the only Chams in that village.

When the villagers who were evacuated at the same time as my sons returned home, they told me they had seen two young men whose skins were like Vietnamese along with a beautiful woman; they were trying to find their mother. One of the villagers said he saw all three of them being taken away by the Angkar to be killed. The villagers also described their appearances. They said one man had curly hair and the other one had straight hair. On hearing this, I was heartbroken; I knew it was my sons. Even though the base people told me that Smael and Yousib were killed by the Angkar, I still have a feeling that Smael is probably alive. But, Yousib probably died because his face in the photo has become very pale. I went to see a fortune teller who told me that both of my sons are still alive; one of them had lost a leg, but both would come home in the month of Chet. I have waited through many months of Chet for them by now."

Kong Sarifas

Pictures of Ly Yousib and Ly Smael that their mother, Kong Sarifas kept with her. Photo/DC-Cam Collection of Khmer Rouge Victims Belongings

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

From 1992 to 1995, following the collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), it is estimated that more than 100,000 people were killed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. 80 percent of those killed were Bosniaks, the predominantly Muslim population, while two million people were forced to flee their homes. Concentration camps were set up; thousands of Bosnian women were systematically raped. In July 1995, in what has been established by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia as an act of genocide, more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were executed by the Bosnian Serb forces in the town of Srebrenica, in addition to more than 20,000 civilians expelled. Srebrenica was a United Nations-declared “safe area”. This was the largest massacre in Europe since the Holocaust and despite prompting a ceasefire that led to the end of the war, the genocide left deep emotional scars on the survivors, families of victims, and the Bosnian and Herzegovinian society in general, creating enduring obstacles to reconciliation among the country’s different ethnic groups.

This was the largest massacre in Europe since the Holocaust and despite prompting a ceasefire that led to the end of the war, the genocide left deep emotional scars on survivors and the Bosnian society in general, creating enduring obstacles to reconciliation among the country’s different ethnic groups.

Selma Jahić

Grandfather’s watch. Photo/Selma Jahić

The story of this watch is very dear to me. This watch belonged to my beloved grandfather, Suljo Salko Jahić. He was not just my grandfather but more like my second father. During the war from 1992 to 1995, we, my mother my little brother and I lived separated from my father for four years. My father was not able to return to Bosnia at the beginning of the war. He worked in Belgrade, and when the war broke out he was trapped in Serbia. Soon he had to flee from Serbia with no chance of returning to Bosnia. He left and somehow was able to travel to Austria where he then tried to get in contact with us. Which was very difficult at that time.

During the war, there was a lot of censorship and letters were confiscated by the Red Cross (sic.). You were not allowed to write about death or the war. Sometimes months would pass before we were able to contact my father. He never knew if we were alive or if we had been killed.

This whole time my grandfather became something like a second father to my brother and me. Grandfather was a very strong and proud man. He loved us dearly. He was mostly an introvert, who loved to take care of his animals and did not like to talk to people. He was a person who only talked if he had something important to say. I followed him all around like a little puppy. He took me with him when he chopped wood or when he took our cow to graze.

I was, and still am, very proud of my grandfather.

My grandfather became our protector, even though he was a man in his seventies. I remember the last day we saw him. We were all ordered to go to Potočari, on the 10th of July 1995, because Srebrenica has been occupied by the Serbian army. My aunts were there with their kids. I remember Grandfather had his best clothes on. He never left the house in dirty clothes. He had on his black beret, white shirt, black blazer and black trousers."

We were deported on the 13th of July. My grandfather and grandmother stayed behind. On the day we left Srebrenica the temperature was unbearable. Many fainted. We had no water to drink. That’s why my grandparents decided to wait until the next day and leave then, hoping the weather might be cooler. We trusted the Serbian soldiers who told us, “Who wants to leave, can leave, and who wants to stay, can stay. No one will be harmed.” Later we would all find out what really happened to those who stayed behind.

So, we left with the promise of seeing them tomorrow. We were to be deported with a truck. There was an elderly couple in front of us. The Serbian soldiers tried to separate the husband from the wife. The elderly woman pleaded with them and her husband too, to let him leave with his wife because she was ill. They told the wife: “Don’t worry, you’ll find him in the Drina.” And they pushed the wife to go onto the truck and separated the husband to the side. I remember that my mother almost crushed my hand while watching this. She was shaking. I did not know what was wrong.

When we arrived at the refugee camp, people soon realised what was happening with those who were separated. Women screamed and cried in agony. I asked my mother where my grandfather was. She told me that he was gone.

I was 7 when we left Srebrenica in 1995. Now my parents, my brother and I live in Austria.

In 2007, my aunt, my father’s sister, called him at work and told him that they received a letter from the red cross. They had found my grandfather’s remains. My father called me at home. I remember the moment like it was yesterday. It was the summer holidays. He just said: “They have found grandfather”. I put the phone down. Went to into my brother’s room and told him the news. After that, I left our flat and walked around for hours. I can’t remember where I went. I just had to get out. After that, I went home and cried.

I was not there when he was buried. I was mentally not strong enough to go. Years later my father showed me the photo with the items that were found with his body. I saw this watch and asked if I could have it. He asked his sisters in Bosnia if they were okay with that. My aunts were more than happy to give me a piece to remember him by because they knew how much he meant to me.

This watch was found with the remains of my grandfather, Suljo Salko Jahić. His body was found in two separate mass graves. Some body parts are still missing.

I will always remember him as a strong but quiet man. Who taught me so many things about nature and animals.

I’ll never forget you grandfather."

Selma Jahić

Mela

Mela’s Ballet Shoes. Photo/War Childhood Museum.

When I enrolled in ballet, of course I wanted to stand on my tiptoes. I don’t know how I managed to wait until I was ten years old for my first pointe shoes! I got them from the theatre, just like all the other ballerinas in my class. Everyone got the “real” pink pointe shoes except for me. I got the white ones, and it made me sad. And jealous. Then my teacher explained to me what kind of pointe shoes they were. She told me that they were Sarajevo pointe shoes, produced in our city until the war started. The ballet students who practiced in them would become prima ballerinas of the Sarajevo National Theatre. These pointe shoes would never be made again. I didn’t become a prima ballerina of the Sarajevo National Theatre. Life took me in a different direction, but my great love for ballet lived on. My Sarajevo pointe shoes remain in a special place."

Reflections by Mela, b. 1984 (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

RWANDA

During the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, more than one million people – overwhelmingly Tutsi, but also moderate Hutu, Twa and others who opposed the genocide – were systematically killed in less than three months. Hundreds of thousands of women were raped.

The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda was intricately planned by Hutu extremists, who leveraged their positions to support and equip militias. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) defeated the Hutu extremist government and stopped the killings.

In the years following the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, more than 120,000 people were detained for bearing criminal responsibility for their participation in the genocide.

To deal with the overwhelming number of perpetrators, Rwanda sought a judicial response that was pursued on three levels: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the national court system, and the traditional community court system called “Gacaca”. Since then, Rwanda has embarked on an ambitious Justice and Reconciliation process with the aim of all Rwandans once again living side by side in peace. A key homegrown initiative is Ndi Umunyarwanda, which means 'I am Rwandan'. It is a programme initiated to build a national identity based on trust and dignity. It aims to strengthen unity and reconciliation among Rwandans by providing a forum for people to talk about the causes and consequences of the genocide as well as what it means to be Rwandan.

Reflections by Immaculée Mukantaganira

(Muko, Rwanda, December 3, 1954 -)

Raissa Umutoni’s Dress London, United Kingdom, ca. 1994. On loan courtesy of Immaculée Mukantaganira. Photo/Jim Lommasson.

Immaculée’s daughters, Raissa (left) and her sister Clarisse, Gikondo, Kigali, 1993.

Raissa Umutoni was wearing this dress on June 12, 1994. When the 1994 genocide took her. This was a beautiful dress. Raissa wore it with a white sweater and sandals. She looked beautiful in that dress. Her father, Thaddée Ruzirabwoba, took every opportunity to take a picture of her especially after work as he enjoyed being with them.

You can see here that colors faded but the dress’s parts stick together.

Raissa cried during the nights calling for our attention couple times. Her dad would not let me go and console her and convince her to go back to sleep. Her young brother kept me busy and her dad would not let me get up in the middle of the night. “You are tired, you were busy all day, let me help her, I have to help you.” So, I did not have to worry about Raissa or Clarisse, dad would get up, change them, give them milk and then convince them to go back to sleep.

Thank you honey! You were unique!

Dress was bought from London by one of our friends, who travelled to Europe. Thank you Charles, you have been a blessing to Thaddée, my children and I. Our children were the center of our home, budget, celebration, holidays, family turned around the needs of our kids. I am so grateful that we provided to them all they wanted (they were very happy). I was very much blessed to look at them holding hands knowing they had a bright future. Clarisse and Raissa were very bright kids and we were proud parents. I will always remember you with gratitude.

Immaculée Mukantaganira

Raissa Umutoni’s Dress (6/12/1994)

Raissa was three when the 1994 [genocide] took her life.

This dress was white and Raissa wore it when she dressed nicely for event that happened in the evenings. This reminds how my husband was a provider to our family. My children were always dressed properly and nicely. Their dad travelled a lot and would buy clothes and shoes for them and I. Today, when I got to the mall, I feel so desperate to not have them and spoil them with nice dresses. At a certain point, I could spend a year without going to the mall. Why go? To do what?

Raissa and Clarisse, my daughters were always neat and loved to dress up and enjoyed it. Their dad allowed them to do so; probably God knew they needed that attention. They had 3 years/5 years to be spoiled.

Dear friends seeing this exhibit; Please let your children enjoy your love and presence! Let them know you love them. Spend enough time with them; do not let any occasion without making them happy. They need it, deserve it. Because, there is the thing God never tells us: “How long we have them or we are with them!!”

Thank you Thaddée, Love you!

Immaculée Mukantaganira

Raissa Umutoni’s Cardigan. London, United Kingdom, ca. 1994. On loan courtesy of Immaculée Mukantaganira. Photo/Jim Lommasson.

Immaculée’s daughter Raissa, Gikondo, Kigali, 1994.

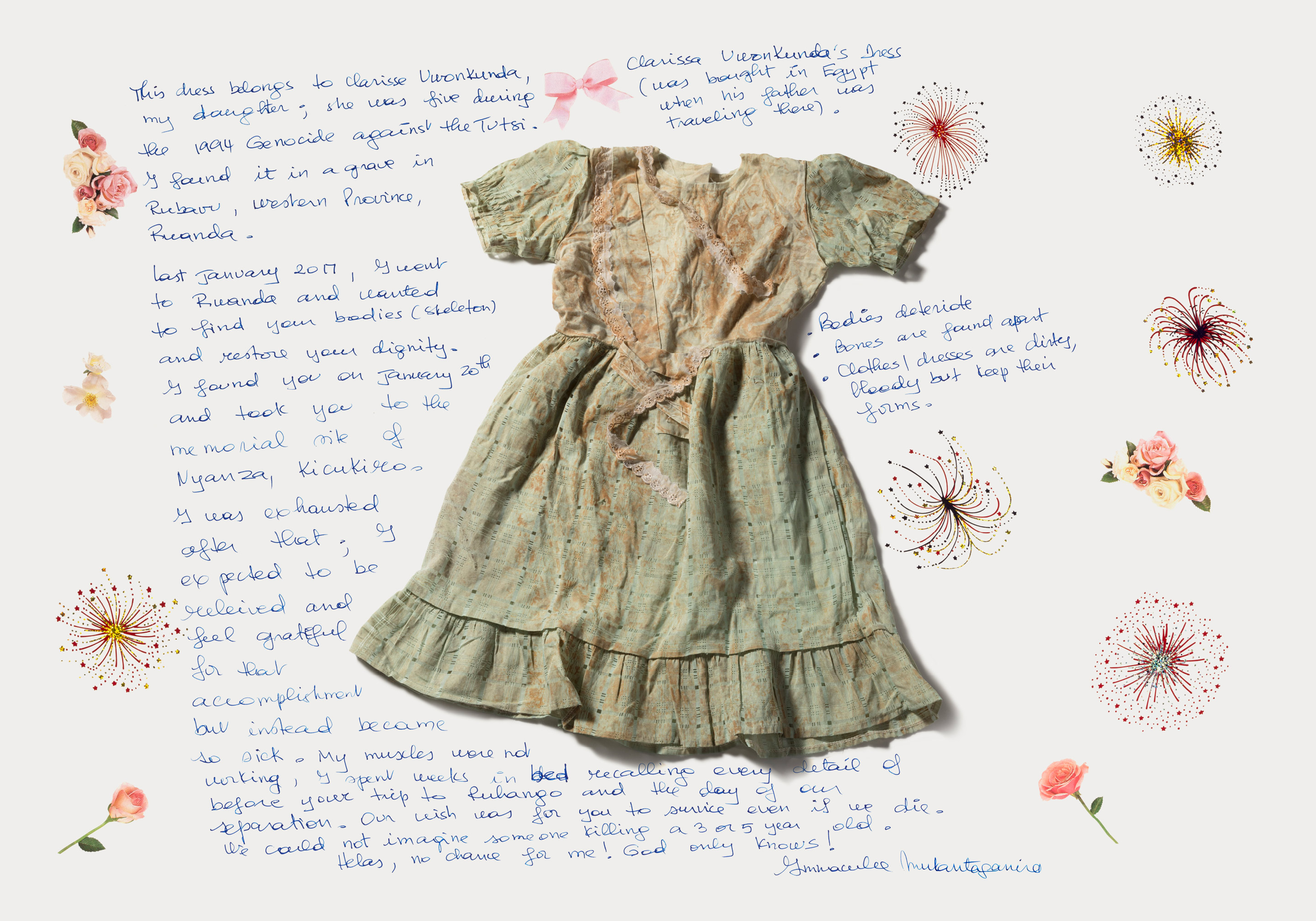

Clarisse Uwonkunda’s Dress Egypt, ca. 1994. On loan courtesy of Immaculée Mukantaganira. Photo/Jim Lommasson.

Thaddee, and Clarisse, Gikondo, Kigali, 1994 Egypt, ca. 1994.

This dress belongs to Clarisse Uwonkunda, my daughter; she was five during the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. I found it in a grave in Rubavu, Western Province, Rwanda. Last January 2017, I went to Rwanda and wanted to find your bodies (skeleton) and restore your dignity. I found you on January 20th and took you to the memorial site of Nyanza, Kicukiro. I was exhausted after that; I expected to be relieved and feel grateful for that accomplishment but instead became so sick. My muscles were not working, I spent weeks in bed recalling every detail of before your trip to Ruhango and the day of our separation. Our wish was for you to survive even if we die. We could not imagine someone killing a 3 or 5 year old.

Helas, no chance for me! God only know!

Immaculée Mukantaganira

Clarissa Uwonkunda’s Dress (was bought in Egypt when his (sic.) father was traveling there).

- Bodies deteriorate

- Bones are found apart

- Clothes/dresses are dirty, bloody but keep their forms

Family Photo Album. Rwanda, 1990s. On loan courtesy of Immaculée Mukantaganira. Photo/Jim Lommasson.

Dear Thaddée,

These photos are remains from your dedication to our family. Do you remember how you came from work, put on your shorts and played with our children! They loved that time and you loved taking their photos. When I miss you, when I think of you, when I am lonely, I look at them and cry. Thank you so much for loving me until your last day! Thank you for leaving behind a legacy of love. You were an exceptional husband and I love you dearly.

To Raissa (she was 3) and Clarisse (she was 5), you have been a blessing and I thank God for the few years you gifted me with your love. I would never imagine myself living without you. Even today, you are a driving force in my life. I want to be able to see you again.

Love you so much!

Mother; Wife; Immaculée Mukantaganira

Clarisse Uwonkunda learning to walk. Her cousins had spent the night in our home visiting in 1990.

Thaddée Ruzirabwoba was also killed in the genocide again the Tutsi in Rwanda. He is the father of Clarissa and Raissa who also did not escape the Genocide.

Immaculée, Mishawaka, Indiana, ca. 2000.

A call to ACTION to prevent genocide

What is the United Nations doing?

The United Nations Office for Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect

Established in 2005, the Office reports directly to the Secretary-General.

The Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide is mandated to raise awareness of the causes and dynamics of genocide, alert the Secretary-General, and through him the Security Council, where there is a risk of genocide, and to advocate and mobilize for appropriate action.

The Special Adviser on the Responsibility to Protect leads the conceptual, political, institutional, and operational development of the Responsibility to Protect principle.

The Office collects information, conducts assessments of situations worldwide and alerts the Secretary-General, and other relevant actors, to the risk of atrocity crimes, as well as their incitement. The Office also undertakes training and provides technical assistance to promote a greater understanding of the causes and dynamics of atrocity crimes as well as enhance the capacity of the United Nations, Member States, regional and sub-regional organizations, and civil society to prevent atrocity crimes and develop effective means of response when they occur.

What else?

Increasing awareness of atrocity crimes through Outreach Programmes: The United Nations has mandated public outreach programmes that educate about the Holocaust and the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, so as to try and help to counter future genocides. This exhibition is an example of the activities and educational resources developed by the Outreach Programmes.

Multilateralism: The United Nations provides support for Member States to have stronger collaboration among countries. In this way, a sustainable path to a peaceful, stable, prosperous world can be built.

Peacekeeping: UN Peacekeeping helps countries navigate the difficult path from conflict to peace. UN Peacekeeping protects civilians, prevents conflict, builds rule of law and security institutions, advances political solutions to conflict, promotes Human Rights, women, youth, peace and security, and delivers operational support. UN peacekeeping observes three principles: consent of parties; impartiality; non-use of force except for self-defence and to defend the mandate.

Countering factors that can drive atrocity crimes such as exploitation and inequalities.

The Strategy and Plan of Action sets out the commitment of the United Nations to address and counter hate speech

- Commitment 1: Monitor and analyse hate speech

- Commitment 2: Address root causes, drivers and actions of hate speech

- Commitment 3: Engage and support the victims of hate speech

- Commitment 4: Convene relevant actors

- Commitment 5: Engage with new and traditional media

- Commitment 6: Use technology

- Commitment 7: Use education as a tool for addressing and countering hate speech

- Commitment 8: Foster peaceful, inclusive and just societies to address the root causes and drivers of hate speech

- Commitment 9: Engaging in advocacy

- Commitment 10: Developing guidance for external communications

- Commitment 11: Leveraging partnerships

- Commitment 12: Building the skills of United Nations staff

- Commitment 13: Supporting member states

In 2019, the United Nations Secretary-General launched the United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech with two overriding objectives:

- to enhance UN efforts to address the root causes and drivers of hate speech in a coordinated way, with a focus on education as a preventive tool to raise awareness and build unity.

- to focus on the United Nations response to the impact of hate speech on societies, with an emphasis on engaging with relevant actors, strengthening advocacy, and developing guidance for counternarratives.

The Strategy recognizes that hate speech is a precursor to atrocity crimes, including genocide. This was the case in the Holocaust as well as in Rwanda, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Cambodia. The United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect is the focal point for the Strategy and supports its implementation across the United Nations system and with other relevant actors.

What can you do? Here are a few ideas:

- Educate yourself: Learn about the warning signs and causes of genocide. Use your knowledge to counter the spread of disinformation and misinformation.

- Get involved: Become familiar with organizations that work to protect human rights and prevent genocide. Follow the United Nations #NoToHate campaign to learn more and counter the spread of hate speech.

- Foster a culture of mutual respect: Promote a culture of peace and non-violence that includes respect for diversity and non-discrimination. This way we can build societies that are resilient to the risk of genocide.

WHAT WILL YOU DO?

This exhibit was launched in April 2023